The Relevance of Revival

What Nathan Irvin Huggins’ 1971 History, Harlem Renaissance, Can Still Teach Us About Our Future.

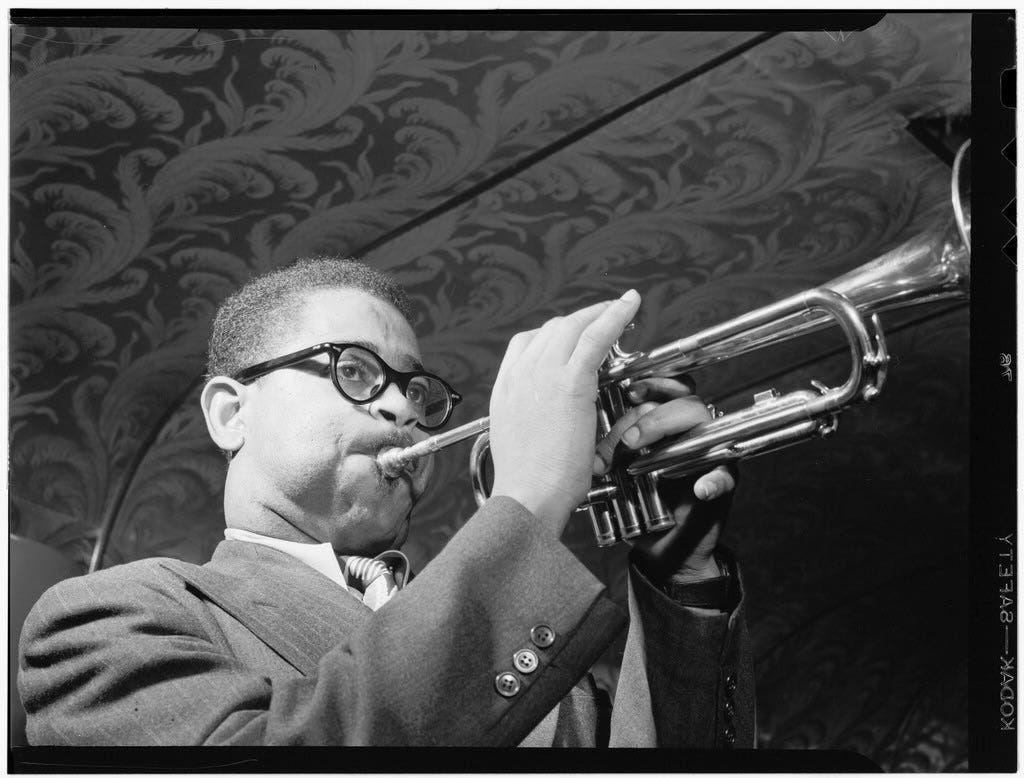

CAPTION: Dizzy Gillespie, playing the trumpet at the Savoy, Harlem, 1947. Library of Congress.

By Guest Contributing Writer Jason Voiovich

If historians pay attention to the Roaring 20s at all, they do so with a certain…haughtiness. The decade following the so-called “Great War” certainly ushered in an era of progressive social policy—some good, some bad—but the attempt at high-brow exploration quickly devolves into a simple trope. Unable to (legally) drink alcohol, Americans became drunk on consumerism. After a decade-long bender, they faced a decade-long hangover: the Great Depression. The 1920s were a cautionary tale. Nothing more.

That’s probably the history you learned in high school.

(Don’t believe me? Search for 1920s history on Amazon. You’ll find only a couple hundred books that focus on the subject. Mine is one of them. Compare that to over 6,000 books on World War II.)

It’s wrong, of course, but how much time do teachers have in a typical American History curriculum? Colonization, Revolution, the Civil War, Reconstruction, Mass Migrations, Two World Wars, and Civil Rights—that’s a lot to cover. I sympathize with high school teachers.

By contrast, I can focus my attention on the history of innovation, consumer behavior, and choice-making. With a narrower set of topics to cover, authors like me can dive deeper. However, that’s not always for the better. Most innovation and consumer culture histories focus on the Model T, frozen foods, gangsters, and Prohibition—but they do so individually, not as a cohesive group. They’re fun stories, and they can be instructive, but they all suffer from trees-versus-forest-itis.

This is a long way of saying that when you holistically study the comprehensive history of consumer culture in the 1920s, you can’t fail to notice the impact of Black culture. And that takes us to the Harlem Renaissance and one of its clearest historians, Nathan Irvin Huggins.

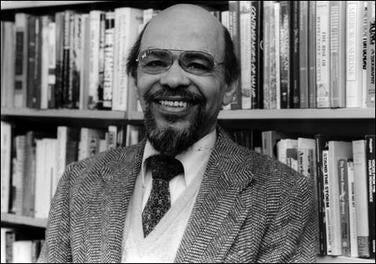

Huggins earned his Ph.D. in History at Harvard in 1962. His scholarship focused on a broader interpretation of American history to include all Americans, and more specifically, Black Americans. To that point, histories focused on the United States from (primarily) one perspective: White, Anglo-Saxon, Protestant…and if we want to get particular and add a couple of ideas, Elite and Yuppy.

(I like how that turns WASP into WASPEY. It’s more appropriate to include wealth and class. No historian before that time was taking poor, rural folks seriously, no matter their skin color or ethnicity, unless they wanted to use them to make a political point.)

This was about the same time (the 1960s) other scholars were including Indigenous groups, gender studies, and second-wave feminism in their research. It was a rich time for scholarship that expanded what it meant to be an “American.”

Huggins’ main contribution was to detail the impact of slavery both on the enslaved and the enslavers. For the latter, that meant a northern migration that most of us remember from high school history. However, it also meant a transition from a rural backcountry life to a new urban sophistication. That change of consciousness awakened a new Black cultural identity in the United States, and no place saw a more profound impact of that transformation than Harlem, New York.

His 1971 book, Harlem Renaissance, was written more than 50 years after the peak of the transition in the Roaring 20s, yet it was still enough in living memory to fuel a balance of perspective and firsthand accounts. It’s a unique historical window that passes quickly, and Huggins tapped it precisely. The book forces Americans to look at the Jazz Age from the perspective of the Black urban sophisticates who created it. The movement spanned all aspects of culture—music, dance, art, fashion, literature, theater, and politics.

Some of the impacts were obvious. Jazz is (in the words of documentarian Ken Burns), “America’s Classical Music.” It introduced Black culture to the rest of America in a way they could access and appreciate. In some cases, such as the Cotton Club, that access was more controlled—Langston Hughes compared the experience of Black performers with few or no Black audience members to a “zoo.” The Savoy Ballroom, by contrast, featured an integrated experience focused on music and dance. In later decades, jazz evolved into R&B, rock and roll, rap, pop, and hip-hop.

But it was more than entertainment culture. The Harlem Renaissance sparked a political awakening as well. At first, that manifested as local activism. During and after the war, it manifested as a call for integration. In the 1950s and 1960s, it manifested as the Civil Rights movement—both peaceful and militant.

That last point sometimes brought Huggins into conflict with other scholars. In some circles, Huggins’ critique of Black culture—specifically, that it focused on the E and Y in WASPEY—irritated other scholars. Their point was that the criticism leveled against Black excesses could not compare to the wrongs perpetrated by the dominant culture. However, Huggins remained unapologetic. If Black culture was strong (and he insisted that it was), it was strong enough to handle the critique that scholarship and elites should pay more attention to the family dynamics and economic plight of poorer Black Americans.

There’s so much more to read about Huggins; it’s best to read his book for yourself. I found it an invaluable resource about the impact of Black culture on entertainment culture of the 1920s, yes, but also American culture as a whole. I owe him a debt.

The bigger issue for us all to consider is this: Who is writing history? Why are they writing it? What is their perspective?

This may seem like a pedantic exercise in academic historiography, but it’s a critical question. Huggins wanted to help tell the story of formerly-enslaved Black Americans striving for a middle class lifestyle they saw around them. Yes, they made it their own, but their motivation was to achieve the level of success they could see in the urban centers of the North, not to overturn them.

What they crafted was a unique vision of success; a Black vision of success. But it was also a vision driven by deep desire, hard work, and proud accomplishment in every field their touched. In fact, it was a very similar path taken by other groups and ethnicities in the broader American experience.

To understand Black culture is to understand an essential part of American culture. Learning about Langston Hughes, Frederick Douglas, and Louis Armstrong is not a replacement to learning about George Washington, Susan B. Anthony, and Henry Ford; it’s a complement. Our history is something less without the full picture.

Huggins gave us, perhaps, the clearest and most accessible history of the emergence of Black culture in America. It’s worth reading, studying, and reflecting on.

About Guest Writer Jason Voiovich

In a career that spans more than 25 years, Jason Voiovich has launched hundreds of new products—everything from medical devices, to virtual healthcare systems, to non-dairy consumer cheese, to next-generation alternatives to the dreaded “cone of shame” for pets, to reproductive aides for cows (really!) He’s a graduate of the University of Wisconsin and the University of Minnesota and has completed post-graduate studies at the MIT Sloan School of Management.

His formal training has been invaluable, but he credits his success to growing up in a family of artists, immigrants, and entrepreneurs. They taught him how to carefully observe the world, see patterns before others notice them, and use those insights to create new innovations. History is Jason’s favorite way to observe the world. He believes the people from the past have plenty to teach us about the challenges and opportunities we face today.

Read and subscribe to Innovation History on Substack

Read or listen to Booze, Babe, and the Little Black Dress: How Innovators of the Roaring 20s Created the Consumer Revolution on Amazon

Connect with Jason on LinkedIn

To discuss speaking engagements, contact Jason at jasonvoiovich@gmail.com

Thank you, Diamond, for the opportunity to share the story of historian Nathan Irvin Huggins and the Harlem Renaissance. I hope it encourages people to dig deeper and read his spectacular book.