A Novel Look at W.E.B. Du Bois

With Feature Commentary From Ilyon Woo, Author of the Book “Master, Slave, Husband, Wife.”

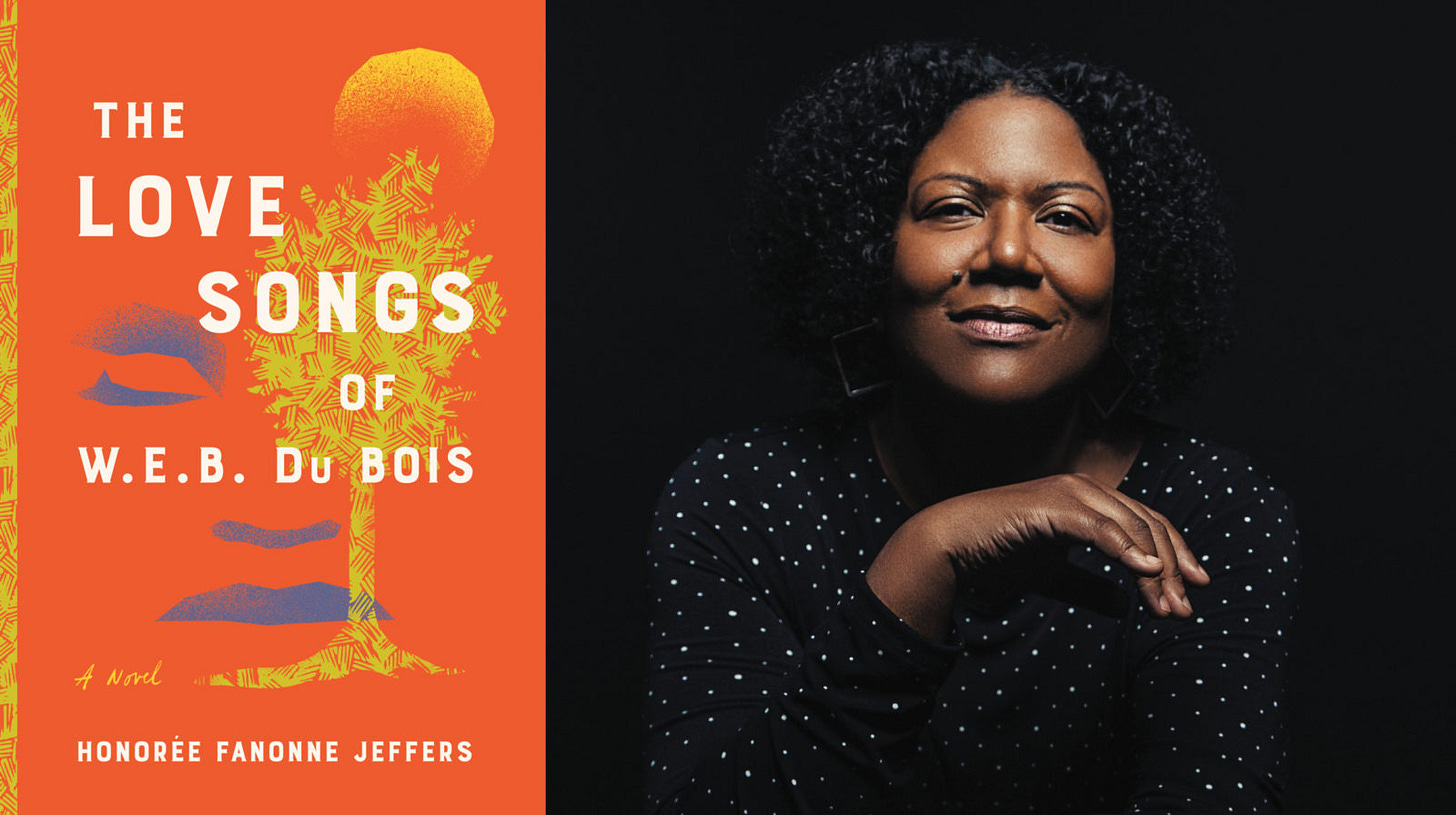

"The Love Songs of W.E.B. Du Bois," authored by Honorée Fanonne Jeffers, is a poignant and expansive novel that delves into the depths of Black history, personal identity, and the enduring impact of the past on our present lives.

Through its rich narrative, the book seamlessly weaves a tale that spans generations, focusing on the experiences of Ailey Pearl Garfield and her family's journey across centuries.

The novel stands out for its meticulous attention to historical detail and the deft way it navigates complex themes of race, heritage, and the struggle for self-identity in a world riddled with discrimination and historical trauma.

Jeffers' writing is lyrical and evocative, drawing readers into a world that is at once beautiful and harrowing. The title, an homage to W.E.B. Du Bois, reflects the interplay of poetry and history that characterizes the narrative.

At its core, the story is about Ailey's journey of self-discovery. Raised in a middle-class family that prizes education and hard work, Ailey grapples with the expectations placed upon her and the history that shapes her. As she delves into her family's past, uncovering stories of slavery, resilience, and survival, Ailey's own identity takes on new layers and complexities.

Jeffers' characters are richly developed, with their stories providing a tapestry of experiences that illustrate the diversity of the Black experience. The narrative shifts between the present and the past, offering a broad perspective on the historical events that have shaped the lives of Ailey's ancestors and, consequently, her own life.

The novel's length and scope might be daunting, but Jeffers' skillful storytelling keeps the reader engaged. Her ability to create a vivid and immersive world is a testament to her talent as a writer. The inclusion of poetic interludes adds a lyrical quality to the narrative, enriching the reader's experience.

The “Love Songs of W.E.B. Du Bois" is a masterful blend of history, family saga, and personal growth. It is a significant contribution to African American literature, offering a nuanced and powerful exploration of identity, history, and the enduring legacy of the past. This novel is not just a story; it's an experience, one that leaves a lasting impression on its readers.

Feature Commentary From ILYON WOO, Author of the book “Master, Slave, Husband, Wife.”

I had the pleasure of featuring Ilyon Woo and her latest book Master, Slave, Husband, Wife: An Epic Journey From Slavery to Freedom in a March 2023 issue of “Black Books, Black Minds.” In that piece I described her book as “ one of the most riveting, suspenseful books I’ve read in years.”

It chronicles the remarkable true story of Ellen and William Craft, who fled slavery through an ingenious blend of trickery and disguise, with Ellen passing as a disabled, wealthy White man and William posing as “his” slave.

Recently, ILYON noted her deep affection for Love Songs of W.E.B. Du Bois, compelling her to re-read and recapture the depth of its essence. I reached out to her with a few questions regarding this sentiment and she was kind enough to respond.

Please describe the central theme of the novel and how it spoke to you?

A book like this contains a world, so I don’t know if I can reduce the themes of this novel to a single one! That said, I can say that, from page one, what spoke to me is the oracular, choral voice. It’s a Classical invocation, where instead of a poetic supplicant screaming at the heavens, “Sing in me, Muse”—of a lone male hero on his journey—the heavens sing out, collectively, as “we.”

As I read it again now, this thrumming plural voice sends shivers down my spine. What flows forth is an incomparable odyssey, with Honorée Fanonne Jeffers as our modern bard, looking like a goddess in the image on the book jacket: gorgeous, mighty, and merciful—but one whose justice you don’t mess with.

Her opening words make me think anew the words William Wells Brown spoke to a Female Anti Slavery Society when they asked him to tell him about slavery “as it was”: “Were I about to tell you the evils of slavery, to represent to you the Slave in his lowest degradation, I should wish to take you, one at a time, and whisper it to you. Slavery has never been represented; Slavery can never be represented.”

These are words I put up on my wall as a daily reminder while writing MASTER SLAVE HUSBAND WIFE.

Honorée Fanonne Jeffers conjures the unrepresentable, in an abundance of what Korean people call han, or passed-down, cast-iron pain, but also, as the title promises, love.

In your view, what did the book reveal to you about the complexities of race, power, and the enduring legacy of slavery in America?

What the book revealed most vividly to me is how little we know. I don’t want to spoil the story, but I’ll say that the archival scraps of paper that emerge (in a chapter so rightly named “Plural First Person”) blew my mind. Jeffers demonstrates to us the insufficiency of the archives—how in every name you may see on the page is a life that is its own tome.

That’s where the physical heft of the book itself is a testament to all the stories once living and still unsung. The body of the book (at 797 pages, it is its own form) makes me think of an extraordinary traveling exhibit I saw this year, called “Hear Me Now: The Black Potters of Old Edgefield, South Carolina.” Here, the artists whose vessels were on display were not marked “Anonymous” or even “Unknown Artist,” but “Potter Once Known.” Jeffers’s incantational work summons what the world once knew, and what we need to know today.

How were you impacted by the book. In what ways did it inform your thinking (directly or indirectly) when writing “Master, Slave, Husband, Wife?”

I’d written much of MASTER SLAVE HUSBAND WIFE by the time I read THE LOVE SONGS OF W.E.B. DUBOIS. But the novel was in my ear as I rewrote it. Jeffers accomplished what I was striving to do on the page: tell a single story, while nodding at other events and strands and rhythms in history that enter into the present moment.

One such nod appears about two-thirds of the way through the book, where I felt like I was seeing friends, and I shared this moment with Ms. Peggy Trotter Dammond Preacely—poet, activist and Freedom Rider—who was reading the novel too. I asked her, “Did you see your ancestors, William and Ellen Craft, on page 600”?

The book’s opening chorus remains in my ear even now, along with the chapter “Plural First Person,” which finally names that voice. I think of LOVE SONGS every time I enter the archives. Thanks to Honorée Fanonne Jeffers’s extraordinary epic, the white spaces on a page will never look the same way again.

"Black Books, Black Minds" stands as the cornerstone of my "Great Books, Great Minds" passion project. It's a labor of love, fueled by tireless hours dedicated to researching and crafting these profound articles.

My mission is clear: to kindle a fresh realm of community, connection, and inclusivity through the wealth of Black History books, the wisdom of thought leaders, and the voices of authors we unearth.

If you're relishing this digital newsletter, finding it not just valuable but transformative, as it explores the rich tapestry of Black History, featuring non-fiction authors and book evangelists, then I wholeheartedly invite you to consider joining us as a paid member supporter.

Your contribution, at just $6.00 per month or $60.00 per year, helps fuel this endeavor and enables the stories of Black History to shine even brighter. Together, we're crafting a narrative that transcends time and enriches our understanding of the world.

Join us in this extraordinary journey.