When President Eisenhower created the U.S. Interstate Highway System in 1956, transportation planners tore through the nation’s urban areas with freeways that, through intention and indifference, carved up Black communities. Overall, within the first two decades of highway construction alone, more than 1 million people had lost their homes nationwide.

My hometown of Columbus, Ohio exemplifies this. In the 1960s, a new interstate highway was built, weaving its way through Ohio’s capital city. Interstates I-670, I-70, and I-71 were built in and around Columbus. Sadly redlined areas were targeted, primarily minority and poor neighborhoods. These included the Near East Side, Milo-Grogan, Linden, and Flytown, the latter of which was completely demolished.

White and affluent areas such as Bexley, where I attended grade school and high school were left untouched. Most notably the I-70 interstate split apart Hanford Village, a formerly independent Black neighborhood. The highway's construction involved the demolition of 60 houses in this middle-class neighborhood.

This was a trend that occurred through the nation. When the U.S. interstate highway system was constructed, spurred by the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1965, many highways were purposefully routed through Black, Brown, and low-income communities. These neighborhoods were destroyed, isolated from the rest of the city, or left to deteriorate over time.

The U.S. interstate highway system, established in 1956 under the Federal-Aid Highway Act, was a monumental infrastructure project designed to connect the nation's cities and promote economic growth. By contrast, highway builders often defended taking property in Black neighborhoods by arguing the land was cheapest there — a fact that relied on government-backed mortgage redlining policies that discouraged investment in Black areas.

This highway construction wave has resulted in significant and lasting impacts on racial discrimination and segregation in several ways:

Displacement of Minority Communities: Highway construction often led to the displacement of predominantly minority communities, as highways were often routed through lower-income neighborhoods. For example, in cities like Detroit and St. Louis, highways were built through African American neighborhoods, resulting in the destruction of homes and businesses.

Segregation: Highways sometimes acted as physical barriers, reinforcing racial segregation. In cities like Atlanta and New Orleans, highways were strategically placed to separate white and black neighborhoods, limiting opportunities for integration.

Unequal Access: Some communities were effectively cut off from economic opportunities and services due to the placement of highways. In Los Angeles, the construction of the Harbor Freeway disproportionately affected Latino communities, limiting access to jobs and resources.

Urban Renewal: Highway construction was often linked to urban renewal projects that disproportionately impacted minority communities. For instance, the construction of I-95 in Miami's Overtown neighborhood resulted in the destruction of a vibrant African American business district.

Environmental Justice: Highways sometimes led to environmental injustices, as they often passed through disadvantaged communities, exposing residents to pollution and health risks. This phenomenon is evident in cities like Houston and Newark.

Efforts have been made to address these historical injustices through various means, such as community revitalization projects and the rerouting of highways. However, the legacy of racial discrimination and highway construction still influences urban landscapes and social disparities in many American cities today.

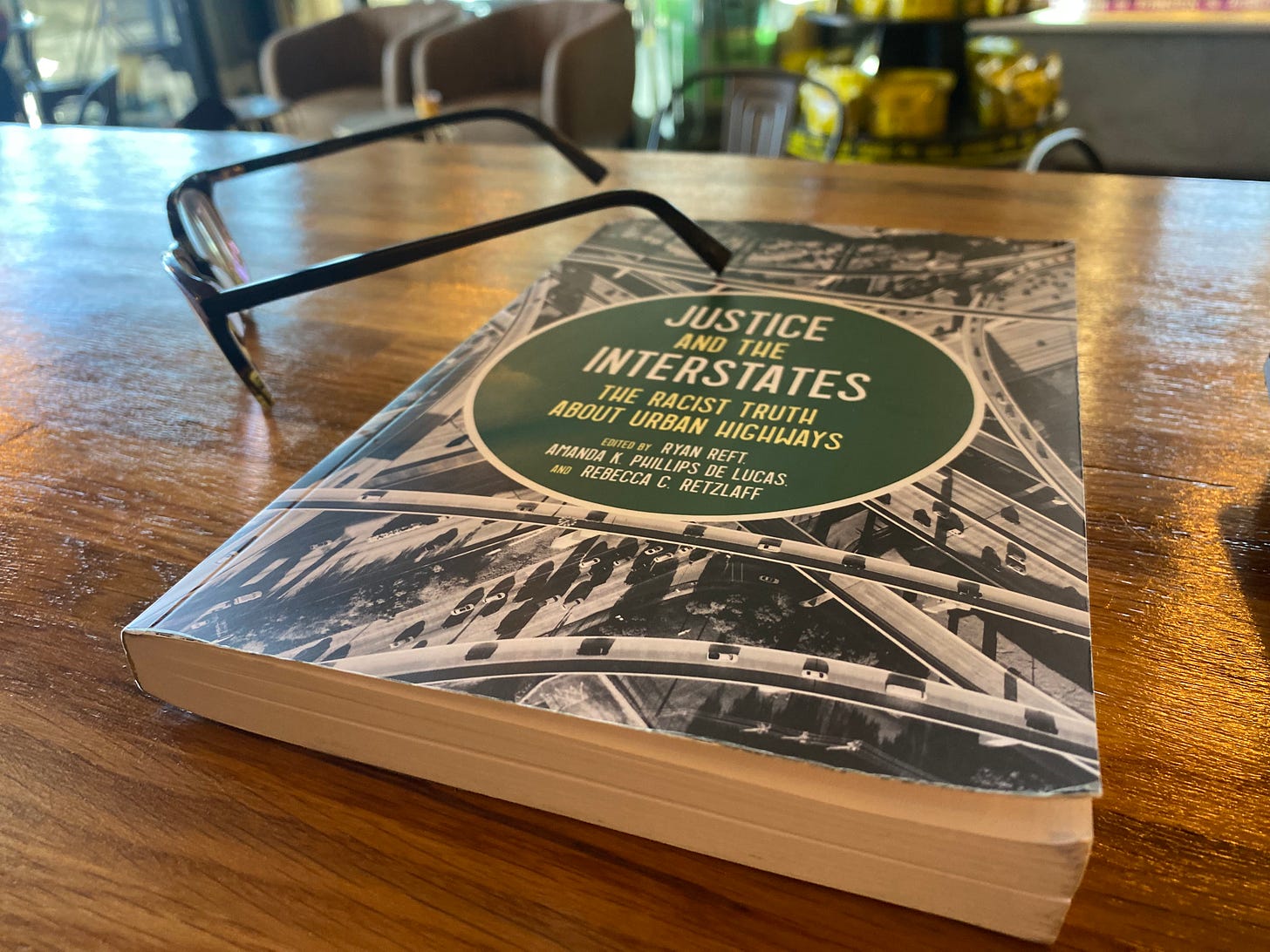

It’s here where we turn to the book Justice and the Interstates: The Racist Truth About Urban Highways, edited by Ryan Reft, Amanda Phillips de Lucas, and Rebecca Retzlaff (Island Press, 2023).

This book examines the toll that the construction of the U.S. Interstate Highway System has taken on vulnerable communities over the past seven decades and how some communities are working to rebuild.

The chapters, written by urban experts and thought leaders, use real world stories to illuminate the injustices of the highway system and current efforts to repair the damage.

Between 1957 to 1977, around one million people were displaced by interstate construction. In Alabama, White supremacists used interstate routing to disrupt the civil rights movement, illustrating how reckoning with racist highway design is a critical part of building a safer, healthier, and more equitable future.

In St. Paul, Minnesota, community-led efforts to restore the historically Black Rondo neighborhood shows a contemporary path to transportation justice.

Throughout Justice and the Interstates, a number of authors detail efforts to restore these often segregated communities. They offer recommendations for moving forward, and call on transportation planners and engineers, urban planners, and policymakers to account for the legacies of their practices.

It provides a concise, thoughtful examination of the damages wrought by highway construction on vulnerable communities in America.

Thank you. Saw this happen in Chicago - the mayor at the time lied to working class ethnic communities - and here in Denver, where the issue has been contested for years regarding the severing of communities by I-70. People take infrastructure for granted as if it was created through acts of nature.