Ada Sipuel Fisher’s Trendsetting Admission to the University of Oklahoma Law School

“I thrive on adversity … If you tell me I can’t do that, I’m going to do it. Was it worth it? Most certainly yes. Would I do it again? Yes.”— Ada Sipuel Fisher

These are the words of Ada Lois Sipuel Fisher, a prominent yet little known activist, attorney and educator who in 1945 completed her battle to become the first Black law student at the University of Oklahoma. Her landmark case opened doors to higher education Black students in the state of Oklahoma while setting a roadmap for segregation cases throughout the U.S.

She was born February 8, 1924, in Chickasha, Oklahoma. in Chickasha, Oklahoma. Her parents moved there from Tulsa after surviving the 1921 Race Massacre.

A significant Black population had existed in Chickasha prior to its founding in 1892. As Black Americans began their nineteenth century migration from the South, the Chickasaw Indian nation brought their Black slaves in great numbers with them, primarily settling in the area.

An outstanding student, Ada graduated from Lincoln High School as valedictorian in 1924. At that time, the Oklahoma state constitution had driven a line between “white” and “colored” leading to the mandate for the racial segregation of schools. As was the case with many areas across the nation, Oklahoma was deeply segregated.

After initially enrolling at Arkansas A&M College at Pine Bluff, she transferred to Langston University in September 1942. It was there where she majored in English with her sights set on becoming a lawyer. On March 3, 1944, she married Warren Fisher. She graduated from Langston a year later with honors.

Langston University, however, did not have a law school, and Oklahoma state statutes prohibited blacks from attending white state universities. Instead funding was provided by the state for Black students to attend law and graduate schools outside of Oklahoma that accepted Blacks.

Prompted by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), Ada agreed to pursue admission to the University of Oklahoma's law school, setting up a challenge to Oklahoma's segregation laws preventing her from pursuing a lifelong dream of becoming a lawyer.

As chronicled by Patricia Sullivan, Professor of History at the University of South Carolina in her book “Lift Every Voice: The NAACP and the Making of the Civil Rights Movement”

“The case of Ada Sipuel was the opening volley in the NAACP’s postwar challenge to segregated education, picking up where Charles Houston and Lucille Buford had left off in 1942. Before that case was aborted due to wartime pressures, Houston was trying to establish that at the level of professional and graduate education, the attempt of states to duplicate opportunities in a racial separate institution was neither economically feasible nor academically possible”

“She (Ada) worked closely with Roscoe Dundee, longtime head of the Oklahoma NAACP state conference of branches, during the application process. When the school rejected Sipuel, citing the state’s segregation laws. Dundee contacted Marshall, advising that Sipuel was prepared to sue for admission to the university, and pledged the resources of the state conference to finance the case. Oklahoma attorney Amos T. Hall was ready to provide local representation.”

So on January 14, 1946, Ada applied for admission to the University of Oklahoma College of Law, accompanied by NAACP Regional Director Dr. W.A.J. Bullock and Oklahoma NAACP leader/editor of the Black Dispatch Roscoe Dunjee. After assessing Fisher’s credentials, university president, Dr. George Lynn Cross, emphatically noted that while there was no academic reason to reject her admission, there were still Oklahoma statutes on the books prohibiting whites and blacks from attending classes together.

So on April 6, 1946, Sipuel-Fisher filed a lawsuit in the Cleveland County District Court, which led to a three-year legal battle. A young NAACP attorney and later the first Black U.S. Supreme Court justice Thurgood Marshall, later agreed to represent Sipuel Fisher. Having lost her initial cashe in the county district court, she appealed to the Oklahoma Supreme Court which sustained the ruling of the lower court in finding that that the state’s policy of allowing segregation in the state was determined to be not in violation of the U.S. constitution.

This led to Sipuel-Fisher’s appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court which on January 12, 1948 ruled in Sipuel v. Board of Regents that the University of Oklahoma must provide Fisher with the opportunity to access the same legal education as it provided to other citizens of Oklahoma.

As Patricia Sullivan notes in her book:

“Immediately following the Sipuel ruling, fifteen southern governors entered into a compact seeking congressional approval of a plan to pool their resources and establish regional graduate and professional schools, a proposal that garnered wide support in Congress during the first half of 1948. At the same time, several states facing litigation established separate facilities in an effort to satisfy the Gaines ruling.”

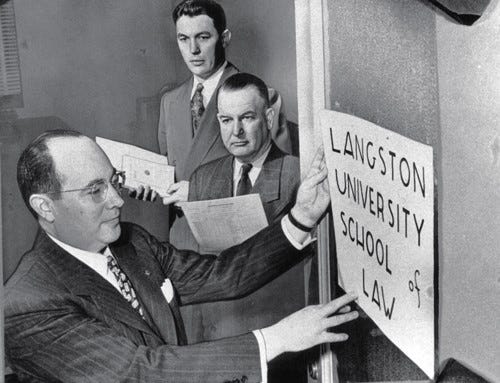

Following the Court's favorable ruling, the Oklahoma Legislature, rather than allow Sipuel-Fisher’s admission to the Oklahoma University law school, elected to create a separate law school exclusively for her to attend. The new school, which was named Langston University School of Law, was created in five days and was to be housed in the State Capitol's Senate rooms.

Refusing to attend, Sipuel-Fisher through her lawyers filed a motion in Cleveland County District Court asserting that Langston's law school would be subpar in its efforts to offer an education equal to what whites received at OU's law school. This, her legal team argued, entitled Sipuel Fisher to admission to the University of Oklahoma College of Law. However, once again, the Cleveland court rebuffed her attempt, noting that the state law schools were "equal." The Oklahoma Supreme Court then upheld the finding.

Persistent, her lawyers announced their intention to appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court. Remarkably, this sparked Oklahoma Attorney General Mac Q. Williamson’s decision to not re-argue in front of the nine Supreme Court justices that Langston's law school was equal to OU's law school. So on June 18, 1949, over three years after Ada Sipuel Fisher first applied for admission to the University of Oklahoma College of Law, she was finally admitted. Langston University's law school was closed down twelve days later.

While Fisher was generally accepted by her white classmates, she was required to sit in the very back of the room in an area designated as “colored.” Throughout the 1950s, Black students enrolled at the University of Oklahoma were provided with separate restroom accommodations, cordoned off reading sections in the library, and roped-off stadium sections at the football games.

In August 1952 Fisher graduated from the University of Oklahoma College of Law. As she walked across the graduation stage at Owen Field, President Cross stood waiting to hand her the diploma.

After a brief stint practicing law back in her hometown of Chickasha, she joined the faculty of Langston University in 1957, serving as chair of the Department of Social Sciences. She later earned a master’s in history at the University of Oklahoma in 1968.

She retired in December 1987 as assistant vice president for academic affairs. In 1991 she was awarded an honorary doctorate of humane letters from the University of Oklahoma.

On April 22, 1992, Gov. David Walters in an attempt to address the wrong of the past appointed Dr. Ada Lois Sipuel Fisher to the Board of Regents of the University of Oklahoma, the same school that had once refused her admission to the College of Law. As the governor noted during the ceremony, it was a “completed cycle” for the woman who was once rebuffed in her attempts to attend the law school was now a full fledged member of the university’s governing board.

On October 18, 1995, Dr. Ada Lois Sipuel Fisher passed away. In her honor, the University of Oklahoma dedicated the Ada Lois Sipuel Fisher Garden on the Norman campus.

Black Books, Black Minds” is a key foundation of my Great Books, Great Minds” passion project. For me, it’s a labor of love fueled by the endless hours of work I put into researching and writing these feature articles. My aim is to ignite a new world of community, connection, and belongingness through the rich trove of Black History books, thought leaders, and authors we unearth.

So if you are enjoying this digital newsletter, find it valuable, and savor world-class book experience featuring non-fiction authors and book evangelists on Black History themes, then please consider becoming a paid member supporter at $6.00/month or $60.00/year. Large or small, every little bit counts.”