“Black people can never count on schools to give us a well-rounded education, one where black history and culture are affirmed.”

Bell Hooks, Author, Rock My Soul: Black People and Self-Esteem

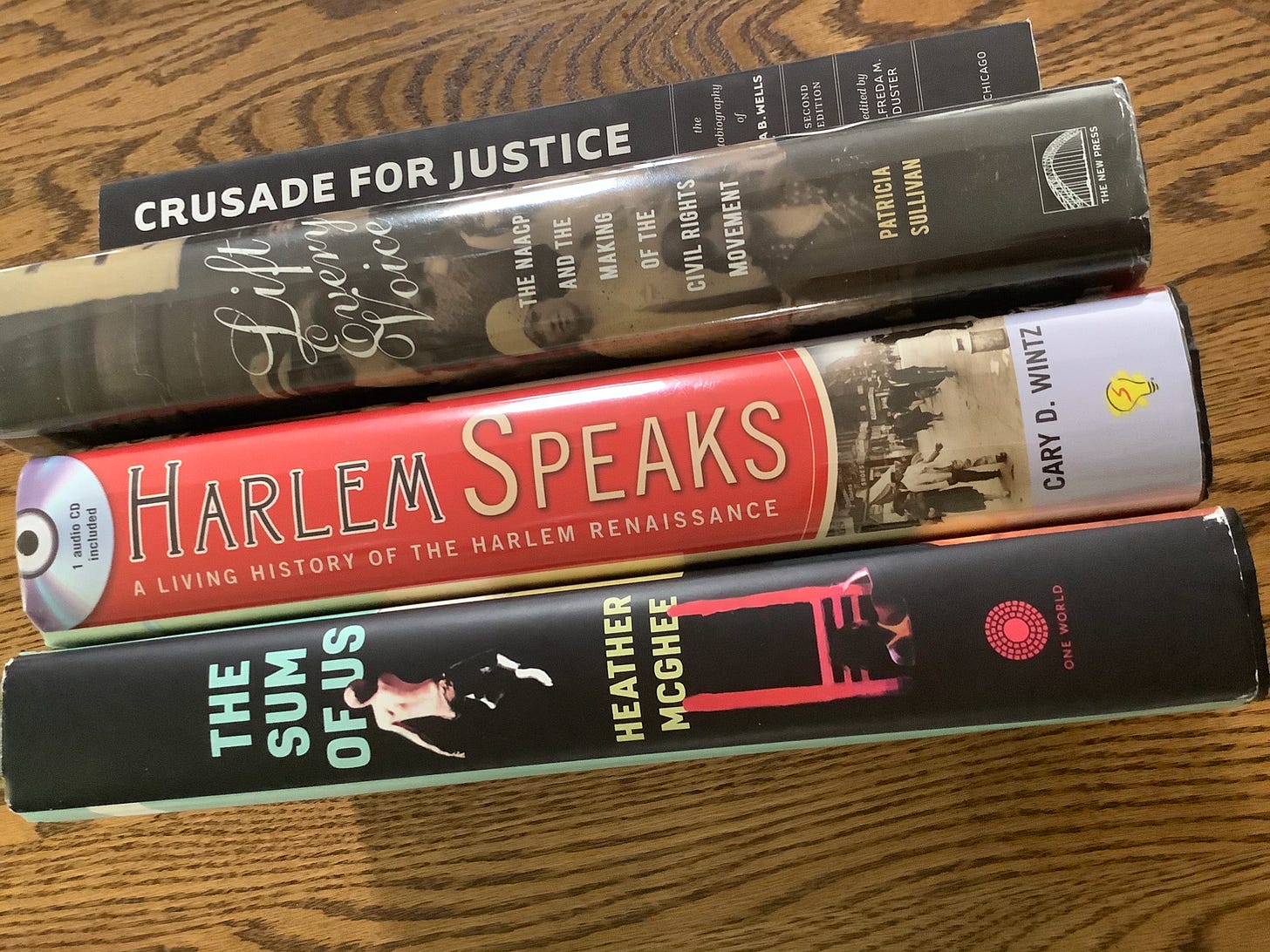

It was the mid-70s and I was entering sixth grade. That year, my mother, in a move that had profound implications on how I view life transferred me from a predominantly black Catholic grade school to one where I was the only fly in the buttermilk.

On that first day, my home room teacher Ms Burnett introduced me to the sea of white students that made up the class. I felt trepidation as I slowly began looking for a seat. Suddenly a young man with a Cleveland Browns shirt blurted out “come sit by me, come sit by me!” He became my best friend from then on through high school.

His name was Michael and he had a love for Civil War history. In fact, the school administration, impressed by his deep knowledge of this watershed moment in U.S. history encouraged Michael to create a play about it.

Later, when we were in the 7th grade the teachers gave him the green light to direct his fellow classmates which included me in a Civil War reenactment — a series of performances in front of our parents in the school gymnasium. I recall being given a choice as to whether we wanted to be on the side of the Union or Confederates. Naive about the distinction between the two, I chose the latter.

Let’s now fast-forward to 1977-81. I attended St. Charles Preparatory School, an all-boys, predominantly white high school in Columbus, Ohio. Over the course of my four years there, I felt intimidated by an environment that essentially viewed me and my small cohort of fellow Black students as academic experiments. Many flunked out. I barely survived, with a 2.4 GPA and a SAT score that was so low that my guidance counselor tried to discourage me from even applying to college.

My favorite teacher though was a white Jesuit priest by the name of Father Thomas Bennett. An affable man saddled with a wide girth due in part to his insatiable love of chocolate, he taught junior and senior level history and government. He was a stern taskmaster, particularly as it relates to one of the school’s requirements for graduation —- memorizing and reciting the names of all the U.S. presidents in order with their years in office.

I’ll readily admit that the broad historical foundation that this exercise offered has proven to be invaluable to me over the years. But looking back at my high school days, the one thing that we received little to no instruction on was Black History.

What’s interesting about this is that I believe that Father Bennett recognized the paucity of Black context in the history textbooks that the school provided to the students. The materials, in fact, were so void of anything even remotely related to Black History that he astutely decided to supplement the classroom shelves (likely out of his own pocket) with copies of Jet and Ebony Magazine.

I recall him loudly announcing to our class one morning that these magazines “are available so that you white students can learn about Black folks. And oh, I suppose that your fellow Black students here will benefit from reading them too.”

Sadly, if my memory serves me right, I recall very little in the way of key historical notations on Frederick Douglass, Madam CJ Walker, Malcolm X, Booker T Washington, Niagara Convention, the NAACP, or any other key figures or events. It wasn’t until I hit my 40s that I began to realize this void in my education and knowledge.

I was reminded of this recently while reading the book “Rock My Soul: Black People and Self-Esteem” by pioneering Black author and feminist Bell Hooks. In an excerpt from the book she notes:

“Racism in education, both in the content of materials and in the manner in which knowledge is presented, has made it almost impossible for institutions of learning to educate for critical consciousness and provide African-American students with the skill to be critical thinkers that is needed for healthy self-esteem. However, the failure to create a learning context that can foster the self-esteem of African Americans cannot be blamed on institutions. The organic learners and intellectuals can educate themselves for critical consciousness if they have mastered the skills of reading and writing.

She then proceeds to point out that “one of the most subversive institutions in the United States is the public library, where citizens can find a fount of knowledge that they can utilize for personal growth.”

Hooks continues:

“From the onset of our history in this nation black people recognized a link between reading, critical thinking, and self-actualization. Placing value on reading continued to be of paramount importance to African Americans in the aftermath of slavery. Publication of slave narratives, the development of the black press, indicated to anyone witnessing the transition from slavery to freedom that black folks needed to be independent thinkers, that they could not rely on the world that had subjugated, exploited, and oppressed them to interpret their reality.”

She writes that if “the sixties and seventies were characterized by the publishing of reading material aimed at racial uplift, self-determination, and attempts to understand race and racism in this nation while working to realize democratic ideals, the eighties and nineties offered the literature of fantasy and escape.”

I was particularly struck by her portrayal of Terry McMillan’s “Waiting to Exhale,” an immensely popular work of fiction that shined a spotlight on a group of Black professional women hell bent on finding a mate and keeping him. Hooks highlights how this focus on searching externally for self-validation and self-esteem sends a message like this to Black folks lacking the capacity to create an inner world of sustainable self-love. She adds:

“The poor self-concept of the black women in this novel and in similar works is accepted as natural and normative. Popular escapist fiction enchants adult readers without challenging them to be educated for critical consciousness. The success of this work affects the work published that seeks to capture younger readers.”

In a concluding thought, Hooks writes:

“Hopefully, we will soon see a day when masses of black people will rush out to buy books that offer us life-based survival strategies rooted in self-love and a collective love of blackness that need never be exclusionary, since our love of race cannot be taken away, nor is it diminished when we openly seek community and contact with folks who are not like ourselves.”

An Invitation from Diamond-Michael Scott

“Black Books, Black Minds” is a key foundation of my Great Books, Great Minds” passion project. For me, it’s a labor of love fueled by the endless hours of work I put into researching and writing these feature articles. My aim is to ignite a new world of community, connection, and belongingness through the rich trove of Black History books, thought leaders, and noted authors

So if you are enjoying this digital newsletter, find it valuable, and savor world-class book experiences featuring non-fiction authors and book evangelists on Black History themes, then please consider supporting my work by becoming a paid member supporter. ($6.00/month or $60.00/year).

Your support will be most appreciated

Indeed a crime. Thank for the personal stories.

Really enjoyed reading this. When I was 6 years old, my parents moved us briefly to Atlanta for my dad's work. We lived in a one-bedroom apartment downtown. I remember touring the local public school (predominantly... if not 99% Black.) My mom wanted to enroll me but the white teacher who gave us a tour actively discouraged it, stating plainly that I wouldn't fit in and would get made fun of. Ultimately, my mom agreed and homeschooled me. I still wonder how that experience might have shaped me. I ultimately got my own crash-course racial education when I supported an ex-boyfriend through his incarceration -- as a Black man, his own understanding of race in America was so profoundly shaped not by his schooling, which was similar to mine, but the books he encountered in prison. Were it not for him I may never had truly engaged with bell hooks, James Baldwin, Edward P. Jones and the non-fiction -- Just Mercy, The New Jim Crow, Worse Than Slavery, etc etc. Reading truly is a key to self-actualization. It still amazes me how much better read some prisoners are as opposed to the some of the men we elect to represent us.

Gotta love the Jesuits!! I'm a Hoya myself. The school still has so much work to do, but I'm encouraged by their commitment to reparations and the Prisons and Justice Initiative.