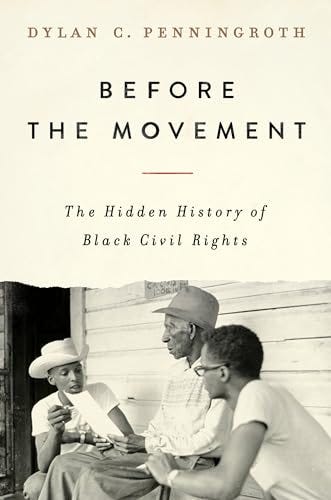

Book Review: Before The Movement

The Hidden History of Black Civil Rights by Dylan C. Penningroth

Book Review By Contributing Writer Marc S. Friedman

Myths concerning Black Americans continue to exist. One myth is that those who were enslaved did not have any money.

Another is that Blacks in the early Jim Crow era did not fight back.

Still another is that all Black people were enslaved until Emancipation.

And one more persistent myth is that until the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950’s, access among Black Americans to the courts was blocked.

These are among many themes highlighted in the ground-breaking book “Before The Movement: The Hidden History of Black Civil Rights”

Based upon decades of prodigious research, Dylan C. Penningroth, a Professor of Law and History at University of California, Berkeley, has uncovered important historical facts demonstrating that even before the Civil Rights era of the 1950’s and 1960’s, Black people in America were familiar with the law and able to use the courts in the North and South to enforce many of their rights.

Penningroth and his students explored 1200 court cases in five states – Virginia, North Carolina, New Jersey, Mississippi, and Illinois, plus the District of Columbia – where a Black person was a plaintiff or defendant. In these cases lies the hidden history of Black civil rights.

“Before The Movement” explains that when the 13th Amendment abolished slavery in 1865 and the landmark Civil Rights Act was adopted in 1866, Black Americans gained what were then known as “civil rights.”

Until that time, these so-called “civil rights” existed only as “privileges” that were granted to them by White people, including slaveholders, and sometimes by Black church associations that extended certain “privileges” to its members. “Privileges” generally included the ability to own and/or occupy land and enter into contracts.

As examples of these “privileges,” the author’s enslaved ancestor Jackson Holcombe “owned” a boat which he used to ferry White passengers across the Appomattox River for a fare. But Holcombe did not have legal title to the boat. His “ownership” was based only on recognition by locals that the boat was his.

And while his agreement to ferry passengers for a fee was not legally enforceable, the local residents recognized the viability of his “carriage contracts” with passengers. These “privileges” granted by Holcombe’s community – the privileges of ownership and contract formation - were not “legal rights” and thus were not enforceable. Holcombe thus could not sue a passenger who refused to pay the agreed-upon fare.

The “civil rights” that Black Americans gained in 1866 did not include the right to be free from racial discrimination. These “civil rights” were more mundane related to the laws of property ownership, contracts, inheritance, marriage and divorce, and associations such churches, and business and activist groups.

These new “civil rights” were recognized by White citizens, including in the Deep South, who understood that the existence and enforceability of these civil rights, for both free Black and White Americans, were critical to a functioning society. Black “civil rights” were quickly recognized by White Americans at the beginning of Reconstruction in 1866 because they knew it was in their own self-interest.

For example, real estate law and the establishment of a “chain of title” to land was equally important to White Americans who were buying, selling, leasing or renting land. Without a predictable body of property law, property rights would be chaotic and uncertain.

As another example, White Americans understood that without a body of predictable contract law, commerce between Black and White Americans, as well as between Black people themselves, would be fraught with uncertainty.

In 1866, Jackson Holcombe’s “privilege to contract” that existed while he was enslaved became a legally enforceable “civil right.” He could enter into a contract to transport a passenger on his boat. Holcombe could then sue a passenger who failed to pay his fare, a classic breach of contract.

However, while White Americans during Reconstruction recognized that Blacks enjoyed and could enforce these “civil rights” through the courts, they were still denying to Blacks what “Civil Rights” later came to mean – the right to be free of racial discrimination in voting, housing, employment, education and access to the courts. These broader “Civil Rights” were not recognized and enforced until the mid-20th Century when the Civil Rights Movement emerged.

Penningroth’s exhaustive case research, done over decades in the deep recesses of rural courthouses, is remarkable. Based upon these case histories, Penningroth understands the legal landscape for Blacks as it existed prior to the 20th Century Civil Rights Movement.

His mission was to see whether the myth of non-access to the court systems was, in fact, just that – a myth. It was. “Before The Movement” established beyond doubt that during Reconstruction and the Jim Crow era, Black Americans knew how to use the court systems across the nation successfully, including in lawsuits against White defendants.

With clear and crisp writing, Penningroth explains how Black Americans use of the courts quickly developed during Reconstruction. They drew on what they knew about the law from the days of slavery, which was substantial.

While they did not have legal protections, many enslaved Blacks understood the power of the law and the importance of having access to it. Many also understood basic legal principles.

Thus, when Emancipation came, they used that knowledge as a foundation for their new “civil rights” in everyday matters, such as leasing farm acreage from their former slave owners and selling their agricultural products at the local market.

Surprisingly, White lawyers, especially in smaller towns, were eager to represent Black litigants, even against White defendants, if there was a legal fee to be earned. Many such lawyers, especially in small law firms, needed the income to survive.

With the help of White lawyers and the very few Black lawyers who were able to enter the profession, Blacks were able to sue to protect their “civil rights” and, of course, they could defend against lawsuits filed against them including by White plaintiffs.

Beginning in the 1870’s, Jim Crow laws were a collection of state statutes and local ordinances passed by racist legislative bodies that essentially legalized racial segregation. These laws created additional barriers to Blacks’ enjoyment of their “civil rights.”

Until the 1950’s, Jim Crow laws made Black American access to the courts more difficult and often impossible. White Americans who ran local court systems no longer extended the same courtesies and cooperation to Black Americans.

Frequently, Black Americans were discouraged from filing or contesting a lawsuit. No longer would White court personnel explain the law to Black Americans or provide them with instructions on how to proceed through the courts.

At times, Black litigants or would-be litigants were threatened with violence by White racists if they did not back down. Yet, Black people bravely persisted in their quest to fully enjoy the “civil rights” that came with Emancipation.

With the struggles for greater freedom that began in the late 1940’s through efforts of activists such as legendary lawyer Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP, and its Legal Defense Fund, the meaning of Black “civil rights” changed dramatically.

NAACP attorneys, from left, William T. Coleman, Jr., Thurgood Marshall and Wiley A. Branton pose outside the Supreme Court in Washington, D.C., in 1958. (William J. Smith/AP file photo)

Especially in the 1950’s and 1960’s, the meaning of Black “civil rights” veered toward Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. 's concept of anti discrimination, economic freedom and the full enjoyment of the panoply of rights belonging to all Americans.

The 1954 Supreme Court decision in the landmark case of Brown v. Board of Education, which rejected the “separate but equal” doctrine of the 1896 case of Plessy v. Ferguson, is one example of how the meaning of Black “civil rights” evolved to become Black “Civil Rights” with capital letters.

As Penningroth states, by focusing only on the later development of Black “Civil Rights” of the “freedom struggle,” historians have overlooked “the vast fields of ‘privileges’ and common-law ‘civil rights’ that Black people had been plowing for more than a hundred years.”

By ignoring the Black experience with the law during Reconstruction and Jim Crow, and even during slavery, an important part of Black and, therefore, American history has been forgotten. The myth that Black Americans had no rights and court access for a century continued.

Penningroth’s book, however, has dispelled the myth and will endure as a testament to Black self-empowerment even under the most adverse conditions.

Referring to Black and White Americans, Penningroth writes,

“…if we want to learn from our shared history, then we must open up our vision of Black legal lives beyond the Constitution and the criminal justice system.”

“Before The Movement” should be read by everyone interested in Black history. Indeed, this is not just Black history, it is American history – and like much groundbreaking historical research often does, it jars pre-existing misperceptions.

As the 20th Century novelist Franz Kafka poignantly stated, “a book must be the ax for the frozen sea within us.” That is because a book can dispel a myth that has become a part of us. This is exactly what Penningroth has brilliantly achieved in “Before The Movement”.

Mr. Friedman was a trial lawyer for 48 years. He was an Adjunct Professor of Law at New York Law School and Seton Hall University School of Law. Mr. Friedman is now an Executive Coach, principally advising law firms and lawyers across the Globe. (www.mastermethod.co).

If memory serves me correctly, the first court case involving a Black person was in the 1700s. I've forgotten the details of the case, unfortunately.