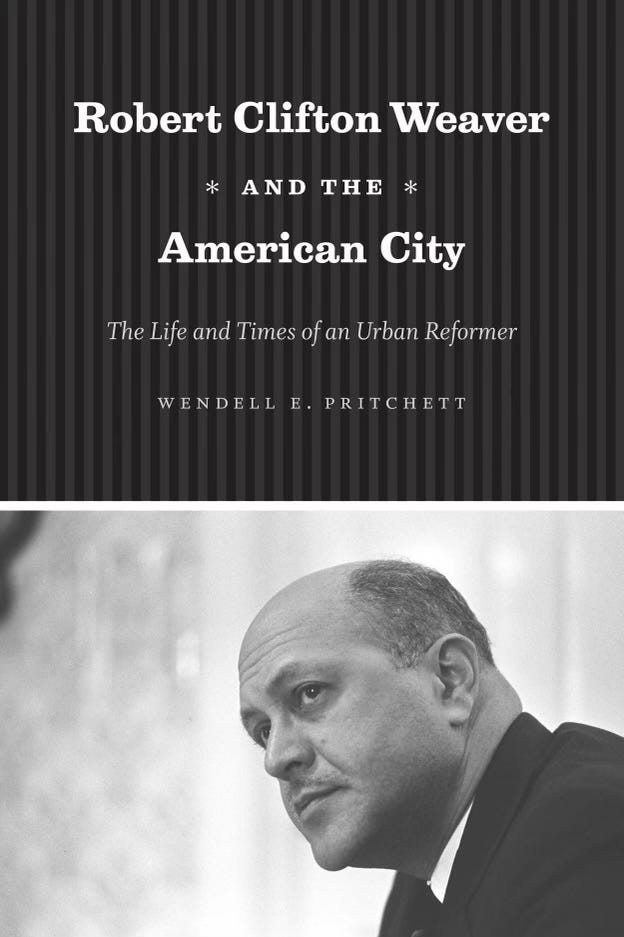

Wendell E. Pritchett’s book “Robert Clifton Weaver and the American City: The Life and Times of an Urban Reformer” is an essential read for understanding not just the man himself, but the broader dynamics of race, urban development, and policy-making in 20th-century America.

The book is more than a biography; it is an exploration of how one man’s career intersected with the complex racial and economic landscapes of the United States, and how his relentless commitment to racial integration in housing has had both monumental successes and profound shortcomings.

In the annals of American history, Robert Clifton Weaver’s name should be as recognizable as any other giant of civil rights and public policy. Yet, as Pritchett reveals, Weaver’s relative obscurity is as much a result of the complicated nature of his work as it is the unfortunate reality of how American society values—or devalues—those who work quietly but forcefully behind the scenes.

Weaver’s role as the first Black cabinet member, appointed by Lyndon Johnson to lead the newly created Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), marked a historic moment in American politics.

However, Pritchett’s narrative suggests that Weaver’s significance goes far beyond this singular achievement. His life’s work represents a nuanced approach to civil rights that avoided the bombast of more militant activists, opting instead for a strategic and intellectual route toward systemic change.

Weaver’s concept of “Radical Liberalism” is a central theme in Pritchett’s book, and it serves as a lens through which to view his career. This approach—attempting to resolve issues with minimal focus on race—was both Weaver’s greatest asset and his greatest limitation.

On the one hand, it made him a palatable figure to the predominantly white power structure of the New Deal and post-war America, allowing him to make inroads where others could not.

On the other, it sometimes muted the urgency of his mission, creating an image of a man who was perhaps too cautious, too deferential to the status quo.

This duality in Weaver’s strategy is what makes his legacy so difficult to assess. Was he a pragmatist who understood the realities of his time, or was he too moderate in an era that demanded more radical change?

Pritchett does not shy away from these questions. He acknowledges the criticisms of Weaver’s approach, particularly in the context of urban renewal projects that, while well-intentioned, often ended up reinforcing the very segregation they were meant to dismantle.

The examples of Chicago’s Robert Taylor Homes and Cabrini-Green, among others, are stark reminders of the limitations of public housing as a tool for social integration.

Weaver’s belief that government intervention could solve the deep-rooted racial divides in American cities was noble, but it often ran headlong into the realities of racial prejudice and economic inequality.

As Pritchett highlights, the persistence of these issues is perhaps the most damning critique of Weaver’s legacy. The urban environments he sought to transform remain, in many cases, as segregated and economically stratified as they were in his time.

The book forces readers to confront the uncomfortable truth that the divisions Weaver devoted his life to bridging are still very much with us.

Segregation in cities like Chicago, where I lived for many years, underscores the stubbornness of these divides. This despite decades of policies and programs aimed at fostering integration.

It’s a reality, mirrored in locales across the nation, suggests that Weaver’s work, while groundbreaking, was only the beginning of a much longer, more difficult struggle.

Pritchett’s biography of Weaver is not just a recounting of one man’s life; it is a call to action, a reminder that the work of social justice is ongoing and unfinished.

Weaver’s story is emblematic of the broader narrative of Black American struggle in the United States—a struggle that involves navigating a society that often sees race as an insurmountable barrier.

His life’s work, as Pritchett eloquently argues, was about more than just housing policy; it was about envisioning a society where one’s race did not determine one’s destiny.

The enduring relevance of Weaver’s ideas, and the continuing challenges of racial and economic integration in America, make this book a crucial read for anyone interested in understanding the complexities of urban reform and civil rights.

Weaver’s belief in the power of government to effect change, tempered by his awareness of its limitations, offers valuable lessons for today’s policymakers and activists.

Pritchett’s thorough and thoughtful exploration of Weaver’s life provides a nuanced portrait of a man who, despite the odds, remained committed to the ideal of a just and integrated society.

In a world where racial and economic divisions continue to shape our cities and our lives, “Robert Clifton Weaver and the American City” serves as both a tribute to a pioneering figure and a sobering reminder of how far we still have to go.

Weaver’s life and work remind us that the quest for social justice is a marathon, not a sprint, and that the road to true equality is fraught with obstacles that demand both persistence and pragmatism.

Join Our Community Today

As a supporting member of "Black Books, Black Minds," you'll dive deeper into a world where your reading passions around Black History thrive. For just $6 a month or $60 a year, you unlock exclusive access to a close-knit community eager to explore groundbreaking authors and books.

You won't just flip through pages; you'll engage in meaningful conversations, connect on a more profound level with fellow book lovers, and enjoy VIP discussions with bestselling authors.

Plus, you'll receive handpicked book recommendations tailored for you. This is your chance to be at the heart of a community where literature bridges souls and authors share their secrets, all thanks to your support.

So join us today. Your participation and support are welcomed and appreciated.