North Lawndale, a Chicago community located on the city’s West Side, has seen its share of tough times. Crime, poverty, unemployment, and property deterioration have dotted the neighborhood for decades.

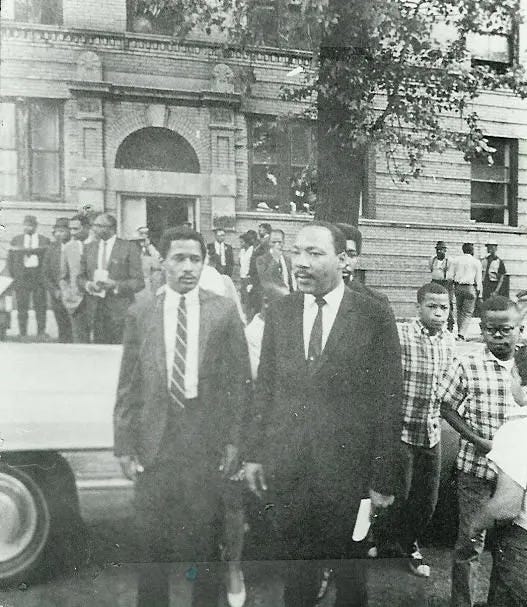

Few know, however, that Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. spent six months of his life in North Lawndale to bring light of the issue he felt was underlying all of this which was housing. In 1966, King brought his fight for justice to Chicago, taking up residence in the neighborhood in a rundown tenement at the corner of 16th and Hamlin.

Fresh off passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, King and his entourage felt that bringing their movement to "the heart of the ghetto" in Chicago, would heighten attention around the substandard housing plight of Black Americans.

On January 26th, 1966 when they first arrived, King and his wife Coretta reportedly encountered a broken door, dirt floors and an "overpowering" smell of urine when they arrived at their temporary home. As was chronicled in Chapter 3 of a book I’m reading entitled “Saying It Loud: 1966-The Year Black Power Challenged The Civil Rights Movement” by Mark Whitaker:

“After eight apartments were rejected as unlivable, (his close confidants ) agreed that a run-down four-room flat renting for $90 a month would be pursued for King in a three-floor walk-up building at 1550 Hamlin Avenue. Afraid that the building’s owner might back out of the deal once he learned the identity of the intended occupant, (one of the members of his) entourage signed the lease himself.”

But according to the book, here’s where things became interesting:

“But when word leaked out that the rental was for Dr. King, the landlord Alvin S. Slavic, had an unexpected reaction. “I’m delighted to have him, Slavic said. ‘What can I say?’ Slavic dispatched four painters, two plasterers, and two electricians to spruce up the building in advance of King’s arrival. Amused by the turn of events, the editors of the Chicago Defender suggested that King might solve the housing crisis on the West Side single-handedly by moving from tenement to tenement.”

“It Wasn’t the Plan, But Dr. King Shows How to ‘Cure’ a Slum Building, “teased the paper’s headline.”

In moving to Dr. King sought to ignite a movement around "open housing.” Despite a 1948 Supreme Court ruling that neighborhood restrictive covenants were unenforceable, Chicago and scores of other cities continue to experience de facto segregation through intimidation and force.

In ensuing years, redlining prevented entire black communities from securing mortgages. Moreover, property owners used predatory contracts to attract black families to crumbling houses at unfavorable rates. As a result, Black residents often faced major challenges amid their desire to move out of slum conditions in places like North Lawndale.

After months of protests, marches and speeches demanding housing justice for Black Chicagoans, then Mayor Richard J. Daley decided to move forward with a "summit agreement" with King, generally agreeing to his demands. Daley vowed to address the discriminatory environment Black’s found themselves under. In return, he asked for a concession, namely that King take his movement to "eradicate a vicious system which seeks to further colonize thousands of Negroes within a slum environment," out of the city.

While the Chicago Freedom Movement played a pivotal role in then President Lyndon B. Johnson signing into law the Fair Housing Act of 1968, scores of Black U.S. communities like North Lawndale still sadly remain among the most poverty ridden in America.