Double-Consciousness and Its Impact On Black Self Esteem

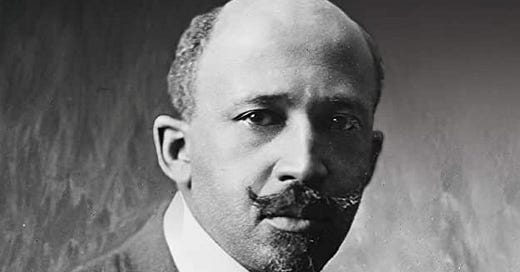

In his groundbreaking book “The Souls of Black Folk,” sociologist, historian, and Pan-Africanist civil rights activist W.E.B Du Bois’ coined the concept “double consciousness,”which he described as “this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others.” While Du Bois’ published his work in 1903, for many Black Americans and their lived experience, double consciousness is still a relevant concept.

From a social philosophy perspective, it speaks to the inward “twoness,” experienced by Blacks because of the racialized oppression and devaluation we have encountered in a white-dominated society. Du Bois described it as a “sensation,” a self-consciousness which falls short of a “true” consciousness. It’s a paradoxical feeling of “two-ness,” of conflicting “thoughts,” “striving” and “ideals.”

Du Bois asserts that “double-consciousness” often forces Black folks to continually view themselves not only as who they really are but by how they might be perceived by outsiders. The effects of this, he says, is a deep and relentless conflict between one’s internal world and predominant external reality.

It was as a 6th grader at a predominantly white Catholic school in Columbus, Ohio that I first began to experience this conflict. Having previously been at a school that swung in the other direction (approximately 70% Black, 30% White), I found myself disoriented by the environment I found myself in.

Somehow subconsciously, I began to realize that in order to be accepted by my school teachers and peers, I needed to act and speak white. No longer was my neighborhood lexicon which included terms, phrases, and behaviors like “give me five, on the black hand side; what’s up my man; and adorning a “Afro” pick in my hair” a safe harbor in this sea of vanilla.

Recently I was reminded of this at a local chamber of commerce event held in Denver where I and the Master of Ceremony were the only proverbial “Flies In The Buttermilk” amid a sea of over 300 fellow attendees.

Many Black Americans find it taxing to come face-to-face with double-consciousness on a daily basis. It’s exhausting to acknowledge what is widely known among my chocolate brothas and sistas as the “Black Tax,” the notion that Black people have to work twice as hard in order to receive the same level of recognition as White Americans.

According to the report entitled. Stuck On The Ladder: Intragenerational Wealth Mobility in the United States, “the median white family in 2019 had a net worth of about $188,000, almost eight times the net worth of the median Black family ($24,000). Differences in mean wealth are even larger: The average white family has about $841,000 more than the average Black family”

So when it comes to advancement in the workplace and society at large, double consciousness and its chilling impact on Black self-esteem is an ever present reality.

As Du Bois chronicled in his writings, Black Americans bore the same duties as White citizens but experienced few civil rights. In an article entitled "Strivings of the Negro People," published in The Atlantic in 1897, he wrote, "To be a poor man is hard, but to be a poor race in a land of dollars is the very bottom of hardships."

This unresolved tension of “two-ness” has also made it challenging for Black Americans to become fully immersed as socio-cultural citizens leading at times to two contradictory worlds: the Black world and the White (American) worlds. For Black Americans the omnipresent nature of this pervasive scenario has insured our invisibility and exclusion from our full humanity.

The broader impact of “double-consciousness” on Black self-esteem is thoughtfully captured in Bell Hooks book "Rock My Soul: Black People and Self-Esteem.” In an excerpt, Hooks notes:

“We black folks have been unwilling to break through our denial and deal with the truth that crippling low self-esteem has reached epidemic proportions in our lives because it seems like it’s just not a deep enough diagnosis.”

She then goes on to add:

“To a grave extent African Americans have colluded with the dominant culture in refusing to document in a substantive way the ongoing psychological impact of traumatic violence. Throughout our history in this nation, black people and society as a whole have wanted to minimize the reality of trauma in black life. It has been easier for everyone to focus on issues of material survival and see material deprivation as the reason for our continued collective subordinated status than to place the issue of trauma and recovery on our agendas.”

Ultimately, Bell believed that “like traumatized people, we need to understand the past in order to reclaim the present and the future. Therefore, an understanding of psychological trauma begins with rediscovering history.”

“Black Books, Black Minds” is a key foundation of my Great Books, Great Minds” passion project. For me, it’s a labor of love fueled by the endless hours of work I put into researching and writing these feature articles. My aim is to ignite a new world of community, connection, and belongingness through the rich trove of Black History books, thought leaders, and authors we unearth.

So if you are enjoying this digital newsletter, find it valuable, and savor world-class book experience featuring non-fiction authors and book evangelists on Black History themes, then please consider becoming a paid member supporter at $6.00/month or $60.00/year.