Chicago has always been a city of neighborhoods, each with its own pulse, rhythm, and personality. But among its many enclaves, few have shaped Black artistic, intellectual, and political life as profoundly as the city’s Bronzeville community.

It was here, on the streets of Chicago’s South Side, that literary greats, visual artists, and musicians forged a cultural movement that aligned with the Harlem Renaissance and the Black Arts Movement.

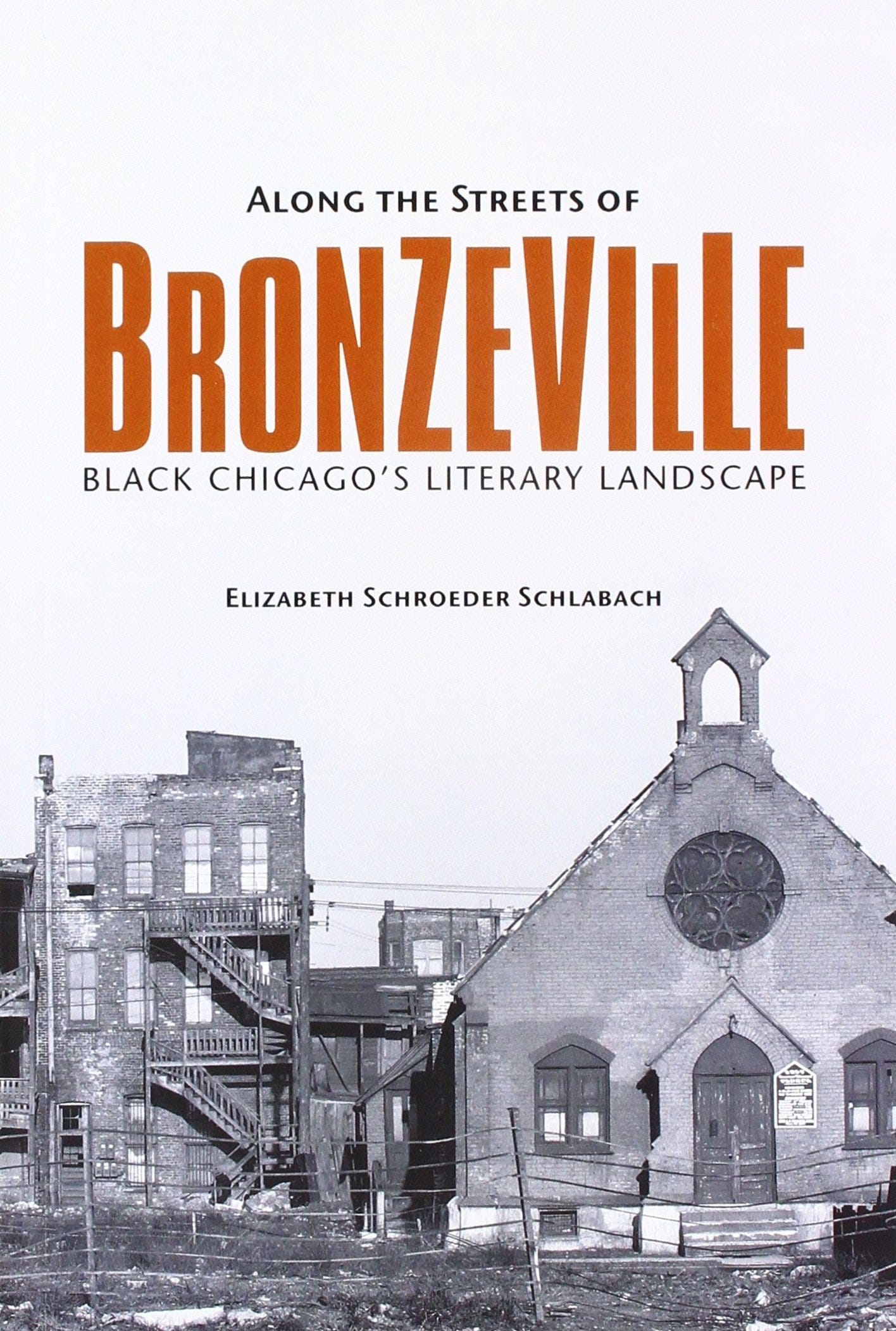

In the book “Along the Streets of Bronzeville: Black Chicago’s Literary Landscape,” Elizabeth Schroeder Schlabach takes us on an immersive journey through the institutions, alleyways, and gathering spaces that nurtured this renaissance.

For me, as someone who spent a number of years in the Chicago area, Bronzeville’s historical significance has always loomed large. Even today, walking through the South Side, you can feel the echoes of Gwendolyn Brooks’ poetry, Richard Wright’s prose, and Archibald Motley’s paintings.

The ghosts of jazz spilling from basement clubs, of heated political debates in corner bookstores, of young writers sharpening their voices on the steps of the South Side Community Art Center—all of it still hums beneath the surface of the gentrifying landscape.

Schlabach’s book is more than just a literary history, it’s a restoration project. She resurrects the places and institutions that fueled Bronzeville’s creative energy, from the infamous “Stroll” on State Street—where blues musicians and poets alike found their footing—to the cramped kitchenette apartments that housed a generation of writers chronicling the struggle for dignity amid segregation.

She meticulously details how the South Side Writers’ Group, the Hall Branch Library, and the South Side Community Art Center created a distinct aesthetic and political consciousness that would influence American literature and culture for decades.

Bronzeville’s Creative Crucible

One of the book’s strengths is how it situates literature within the geography of Bronzeville itself. Schlabach paints a vibrant portrait of Black Chicago’s social landscape in the early 20th century, tracing how the streets themselves—47th and South Parkway, State Street, the blocks surrounding the Victory Monument—shaped artistic expression.

This was a neighborhood teeming with life, from barber shops to pool halls, from blues clubs to the street-corner orators who could match wits with anyone.

The Chicago Defender, a titan of Black journalism, fueled news of migration opportunities from the South with promises of opportunity and dignity, even as it chronicled the struggles Black Chicagoans faced in a city that both needed and rejected them.

Bronzeville was not only a backdrop but the narrative itself. Richard Wright’s Native Son seared into the American consciousness the realities of segregated housing and systemic oppression.

Gwendolyn Brooks, the Pulitzer Prize-winning poet who spent her entire life in the neighborhood, gave voice to the everyday joys and heartbreaks of Bronzeville’s residents in “A Street in Bronzeville.” Langston Hughes, though more associated with Harlem, was profoundly influenced by his time in Chicago, writing of the South Side’s resilience and its nightlife.

A City Within a City

Schlabach doesn’t shy away from the darker realities of Bronzeville. The book examines how economic hardship, segregation, and overcrowding were constants in the community’s evolution.

The dream of the “Black Metropolis,” a self-sustaining Black economy filled with thriving businesses, was constantly under threat from systemic racism, redlining, and urban renewal policies that often dismantled rather than uplifted. The cramped kitchenette apartments—tiny, overpriced spaces where families were forced to live in close quarters—became symbols of both struggle and survival.

Having lived in Chicago, I’ve seen firsthand the remnants of these struggles. Walking past the abandoned sites of former jazz clubs and community venues that once served as local hubs, I’ve often wondered how much of the spirit of Bronzeville has been lost and how much still lingers in the sidewalks, waiting for a revival.

Schlabach highlights how institutions like the South Side Community Art Center provided not just artistic training but a sense of collective purpose. Funded in part by the WPA during the Great Depression, the center became a meeting place for Black artists grappling with what it meant to create in a world that sought to marginalize them.

Here, Archibald Motley’s bold colors and kinetic compositions captured the vibrancy of Bronzeville’s nightlife, while Margaret Walker’s poetry echoed the voices of working-class Black Chicago.

The Decline and the Road to Revival

By the 1960s, Bronzeville—like so many Black urban centers—suffered from disinvestment, white flight, and the destruction wrought by urban renewal projects that displaced thousands. The once-bustling business districts fell into decline, and public housing projects, initially seen as hopeful solutions, soon became symbols of neglect and segregation.

Yet, as Schlabach notes, Bronzeville is not just a story of loss—it is a story of resilience. The spirit of the community endures in its historic landmarks, its literary legacies, and its ongoing revitalization efforts.

The Victory Monument, the Overton Hygienic Building, and the restored South Side Community Art Center stand as testaments to the neighborhood’s enduring significance. Festivals, cultural tours, and grassroots efforts continue to breathe life into Bronzeville, ensuring that its contributions to Black history are not forgotten.

My Personal Reflection

Reading “Along the Streets of Bronzeville” brought me back to my own experiences of wandering through Chicago, absorbing its history block by block. I remember visiting the Harold Washington Library and marveling at the archives of Black Chicago’s literary giants. I recall walking past the old Regal Theater site, imagining the nights when Cab Calloway and Duke Ellington electrified crowds there.

And I think of the times I’ve stood at the corner of 47th and King Drive, reflecting on the generations who had walked those same streets before me—some finding hope, others heartbreak, all of them leaving an imprint.

Schlabach’s book is a love letter to a neighborhood that shaped American culture, a neighborhood whose voices demand to be heard. Bronzeville is more than history; it is a living testament to the creativity, struggle, and brilliance of Black Chicago.

Along the Streets of Bronzeville reminds us that literature is never just words on a page—it’s a place, it is a people, it is a heartbeat that continues to echo through time.

If we listen closely, we can still hear it.

For just $6 a month or $60 a year, you unlock exclusive access to a close-knit community eager to explore groundbreaking authors and books.

Join us today as a paid member supporter. Or feel free to tip me some coffeehouse love here if you feel so inclined.

Your contributions are appreciated!

Diamond Michael Scott, Global Book Ambassador