Feature Interview With Jarrett Adams

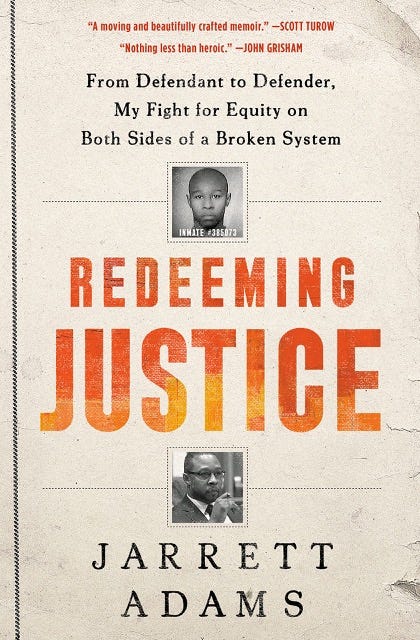

Author of “Redeeming Justice: From Defendant to Defender, My Fight for Equity on Both Sides of a Broken System.”

According to a 2021 report The Color of Justice: Racial and Ethnic Disparity in State Prisons released by The Sentencing Project, Black Americans are incarcerated in state prison at nearly 5 times the rate of white Americans. Nationally, one in every 81 Black adults in the U.S. is serving time in state prison. Wisconsin leads the nation in Black imprisonment, with one in every 36 Black Wisconsinites locked up.

A couple of months ago I was introduced to the book “Redeeming Justice: From Defendant to Defender, My Fight for Equity on Both Sides of a Broken System,” written by criminal defense attorney Jarrett Adams.

As the book’s powerful narrative uncovers, Adams at seventeen years old found himself facing nearly three decades behind bars in Wisconsin for a crime he didn’t commit. As he notes:

“In 1998, I was falsely accused and ultimately wrongly convicted of rape. I was sentenced to prison for twenty-eight years. I, too, had done nothing. I, too, got terrible legal advice. Unlike my clients, I made a catastrophic mistake that set the whole thing in motion, putting me on the path I’m on today. I went to a party. Three of us—three Black kids from Chicago—drove to a college campus in Wisconsin. At the party, we each had a consensual sexual encounter with the same girl, a white girl. Her roommate walked in, called her a slut, and stormed out. These were the facts. But the girl later said we raped her.”

Adams' book offers a sobering account of his incarceration experience and the profound impact that it had on his life as well as his family.

While behind bars — nearly 10 years total — Adams relentlessly educated himself on the prevailing judicial system and the laws undergirding it. He sent voluminous amounts of letters to authorities, attorneys, and the Wisconsin Innocence Project asserting his innocence.

With the unrelenting support and prayers of his mother and aunts, Adams became obsessed with the U.S. legal system and all of its flaws. After discovering that his constitutional rights to effective legal representation had been violated, he reached out to the

The Wisconsin Innocence Project an organization that exonerates the wrongfully convicted played a pivotal role in his eventual release after nearly ten years in prison.

After his release, Adams went on to earn a law degree from Loyola University of Chicago, Adams to a position with the New York Innocence Project, giving him the distinction of becoming the first exoneree ever hired on the legal staff by the nonprofit. In his inaugural case, he argued before the same court where he had been convicted a decade earlier—and won.

Today, through his own law practice, Jarrett Adams has one mission: To apply the legal expertise and life-changing experiences of its founding partner, Jarrett Adams, Esquire, to protect the Constitutionally guaranteed rights of an individual throughout the legal process.

Redeeming Justice is a riveting story of hard work, persistence, and full-circle redemption. Adams draws upon his own personal experiences in the judicial system to expose the racist tactics used to convict and incarcerate young men of color who often lack the legal representation and financial resources to get a fair trial.

Black Books, Black Minds recently had a candid conversation with Adams about his early upbringing, incarceration, and the plight of Black men in America. Here’s what he had to share:

Tell us a little about you and your early upbringing

JA: I’m cut from an old school cloth. I was raised by my grandmother and grandfather for the most part because my mom was a single mother from the South Side of Chicago whose jobs took her to work early in the morning.

What was that experience like?

JA: What I recall are the real, adult conversations my grandparents had with me when I was a kid. And so a lot of my strength was derived from the stories they used to tell me, particularly of how they snuck my aunt and my mom and uncle from the cotton fields of Cleveland, Mississippi.

How did your upbringing inform the writing of your book?

JA: When I looked at life and wrote the book I did so with my eyes wide open. Rather than having it come across as though I was some sort of superhero, I chose to expose my vulnerabilities so that people would start to look at Black boys as boys. Because that’s what they are.

What sort of reaction have you received from the book?

JA: Many people who knew of my story never truly knew the depths of it until they read the book. I say that because the theme of the book is about the throwaway of Black men. So I speak a lot from that point of view.

Can you elaborate more on what you mean by “throwaway of Black men”?

JA: What I mean by that is that there are so many times where you will see a young Black male on the news where they are being accused of something. In many cases, it almost seems as though that person was born at the scene of the accusation without any life prior to then. And these accusations are always tainted with a criminalistic headline or depiction.

What else were you seeking to convey in the book?

JA: It’s interesting now with the release of the book how many people have reached out to me to say ‘man, your mom and your aunts, they had to be the strongest in order to help see you through this.’ What this says to me is that the book has hit the target I was aiming for in terms of working to correct America’s skewed depiction of Black men. I wanted people to understand that Black mothers get it from all sides. You can’t find another species on this earth that is surrounded by so much darkness in terms of the depiction of Black folks and Black boys. Black women always seem to be taking it on the chin for the black family in terms of the dynamics of how things are set up. Much of this is derived from the vestiges of slavery that still exist today.

You say that you wrote the book with your eyes wide open. What are you conveying here?

JA: I wanted to be able to tell young black boys and black women and girls a story that conveys how we should never ever allow someone's perception or society’s perception of us to become our reality.

Are you hopeful in terms of this message?

JA: The hope lies with this – we have to find a way to link arms because minorities are only minorities when they are split amongst the majority. In other words, if we are all finding a way to work together, then we have an opportunity to do what I call “duplication.” What I mean by this is that we have an uphill battle when it comes to producing young, positive Black men and raising them faster than the communities and the prisons are eating them up. So it’s got to be a collective effort.

Where does this effort start?

JA: It begins with figuring out how to save all of these young kids who are being decimated by gun violence and the prison system and drugs. Because in a better world these young kids become the replacements for those who are justice and equity oppressors. The good news is that we are beginning to see more people of color become politically involved as leaders in addressing these issues.

There has been so much talk about the economic factors involved in addressing these issues. Can you discuss this?

JA: Yes, money definitely plays a major role when it comes to our court system. Money, in fact, was a key piece, a fork in the road with respect to my wrongful conviction. Three of us were accused of sexual assault, but only one of us was able to get an attorney. The one who was able to afford an attorney never spent a day in jail. His attorney was able to get to the evidence that the police withheld, namely, a statement from a college student witness that completely undermined the allegations.

Describe the toll of these proceedings on your mother

JA: My mom was coming up to the courthouse for the second trial because the first ended in a mistrial and our trial ended up being severed. At the age of 17 turning 18, things in the proceedings made no damn sense to me. However, I’m looking at my mother and the wrinkles and creases of anger on her forehead thinking “I just wanted it to stop, I just wanted it to stop.”

So what’s your advice to Black youth of today?

JA: Here’s what I’ll say to them. It’s a phrase I’ve shared a number of times – ‘If your turn up, outweighs your turnout, you will be tuned out.’ Our kids are in this turn up phase, everything is turned up, and everything is live in the moment. So it’s cool to have fun but it is also important to know the laws that are afforded to you and know your history.

Can you say more about this?

JA: When this case first began I had an invitation from the police to come down and just tell the truth, right. I was taught as a kid to tell the truth, respect authority, and stuff like that. But this is 1998. At the time I could repeat every lyric from the rapper Tupac’s double CD but I didn’t know anything about our U.S. constitution that would have afforded me my rights.

It sounds like with your law practice you have a calling to address many of these issues we have been discussing.

JA: Yes. We’ve created a non-profit called Life After Justice to both litigate actual claims of innocence and also advocate for changes in the law that protects kids who are going through situations where they are being accused. Because the reality is that a 17-year-old like I was is no match for a skilled investigator in an interrogation room. If telling the truth was all you had to do, I wouldn’t have been wrongfully convicted.

What is your greatest hope for readers of your book in terms of what they walk away with?

JA: I want Black mothers to read this book and have a conversation with their kids earlier rather than later. Have them read it too, about race, sex, interactions with police, knowing your rights, about everything it takes to navigate this society as a young Black man.

Whatever your kids' dreams are, whatever their aspirations are, I would love for them to consider a career in law. Because our country was founded on litigation by litigators. Sadly though, so few of them look like you and me. We need to ensure that this changes.

Jarrett Adams will be our inaugural guest for the first live Black Books, Black Minds BookClub forum held from 8-9 pm ET on Tuesday, June 28th. In this facilitated online discussion, he will discuss his book before entertaining questions from the attendees.

You are invited to attend and can sign up HERE. And please order the book through our online bookstore HERE. Each sale supports “Great Books, Great Minds.”