In 2017, I moved to Las Vegas from Denver. Sadly, at the time, I had zero knowledge or appreciation of the Black historical significance of Vegas.

Fast forward to this month, June of 2023. I am headed back to Vegas with a level of excitement I haven’t felt in years. Maybe it's the fact that I am turning sixty. Or that the Vegas area is on an unprecedented upward tick in positive new developments that bode well for its future.

In recent weeks I’ve had the good fortune of reading the book “Historical Las Vegas: A Cartographic Journey” (University of Nevada Press). It is written by University of Alabama professor and noted geographer Joe Weber who I featured in a piece entitled “A Cartographic Rendezvous Into Historical Las Vegas” for my publication “Great Books, Great Cities.”

So you’re probably wondering what all the fuss is about regarding this book. In short, it’s a book filled with cartographic illustrations that offer a captivating look at Vegas and its surrounding regions. But to my surprise, it includes a number of well-researched excerpts about Black History in Las Vegas.

Noting that the first African Americans arrived in Las Vegas as railroad workers in the early 20th century, Weber adds:

'These workers primarily lived on the north side of Las Vegas, and later some Blacks owned businesses there. Only sixteen African Americans lived in Las Vegas in 1910, mainly near Block 16. Their numbers remained small despite the huge amount of workers needed for Hoover Dam's construction project, which was considered a whites-only job.”

He says in the book that the dam was built by an industrial consortium called Six Companies Inc., which was awarded a contract from the US government for construction of the dam. This agreement, adds Weber, included a clause which barred the hiring of "Mongolians," meaning anyone of Asian descent and noncitizens. Weber then adds this:

“Although allowed to hire Blacks, the company chose only white workers; after complaints were voiced, forty-four Blacks were hired out of the twenty thousand workers employed during the life of the project. They were put to work in the Arizona gravel pits, an unpleasant and demanding place to work with few prospects for upward mobility.”

He continues:

“The new worker town of Boulder City was “whites only, meaning that these few Black workers had to commute all the way from Las Vegas each day. World War I, however, changed everything for as world events drew the United States closer to war, President Roosevelt issued Proclamation 8802 on June 25, 1941, banning racial discrimination in war-related industries.”

The effects of this says Weber in his book….

…..”first became evident a few months later when the BMI project started up in the new town of Henderson (map 4.8). This needed enormous numbers of workers, and labor recruiters scoured the country to find them. Blacks in the South were eager to seek out a better life elsewhere. Two towns in particular, Tallulah, Louisiana, and Fordyce, Arkansas, sent many young workers to help create Henderson and win the war.”

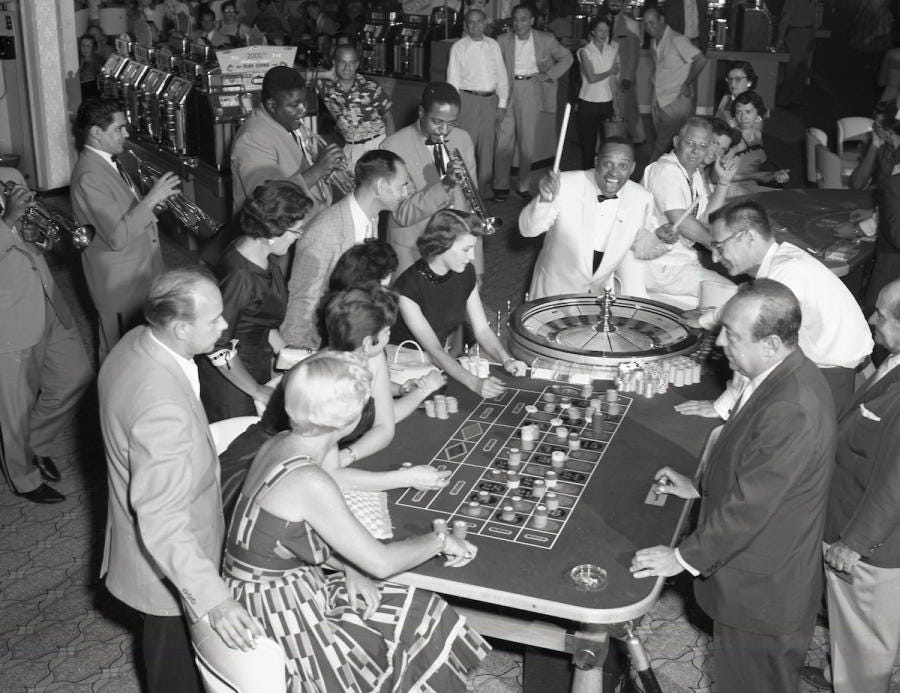

As a bit of a history buff, I decided to go down a digital rabbit hole to learn more about the Black historical narrative of Vegas. What I discovered is that from the 1950s to the early 1960s, in the midst of an economic boom happening in America, Las Vegas experienced a meteoric uptick in economic growth. However, on the heels of this emerged the reality of racial segregation, leading some to coin Vegas due to its blatant racism at the time the “Mississippi of the West.”

Says Weber:

“While Black workers were arriving in Henderson, racial attitudes in Las Vegas changed rapidly for the worse. Whites pushed the small numbers of Blacks living in Las Vegas into the West-side area, essentially making it the city's Black neighborhood.

Black business owners were also told they had to relocate to the Westside to receive a new business license. The wartime boom led to several new housing subdivisions to be built around Las Vegas; all excluded Blacks. As many as three thousand Blacks may have lived in the Westside in the 1940s, enduring severe housing shortages and relatively primitive living conditions.”

Having been forced to live on Vegas’ historic “Westside,” the segregated ten square block of the city across the railroad tracks from Fremont Street, Black residents were subjected to no running water, functional sewage lines, or paved streets. Nevertheless it coalesced into a community that supported one another and lived well because of the wages paid on the Strip.

In May of 1955, Moulin Rouge, the first integrated resort Hotel-Casino opened its doors on the Westside of Las Vegas. Constructed at a cost of $3.5 million and partially owned by boxing champion Joe Louis, it was built with the intention of accommodating Black Americans who were banned from resorts along the Strip. It also afforded Black workers much needed, well-paying jobs in areas such as management and dealing.

While Moulin Rouge declared bankruptcy 1955, it’s success was a major catalyst in fueling the integration in Vegas. In ensuing years, Black workers found employment in "back-of-the-house" positions in the casinos and downtown Las Vegas resorts. Few, however, were allowed contact with customers and guests.

With respect to gaming and entertainment, Black Americans were not permitted to participate in many of the activities Vegas had to offer as they were often barred from gambling, attending shows, and lodging accommodations at establishments.

Among the celebrities who made the rounds in Vegas was Josephine Baker who performed in Vegas for a brief spell in the mid-twentieth century. There was also the renown of Black showgirls like Anna Baker whose work as a performer highlighted the deep complexities and paradoxical nature of race and racism in the entertainment world.

White owners often found themselves in a conundrum given the popularity of Black entertainers amid the prevailing racial mores of the day. Nat King Cole, Dinah Washington, Lena Horne and Sammy Davis Jr. were among the popular figures who were frequently allowed to perform their acts before being ushered to the door. Moreover, they were often relegated to lesser hotel accommodations at exorbitantly higher prices than those commonly seen along the Strip

As Sammy Davis Jr. once noted:

"In Vegas for 20 minutes, our skin had no color. Then the second we stepped off the stage, we were colored again...the other acts could gamble or sit in the lounge and have a drink, but we had to leave through the kitchen with the garbage."

I found myself particularly captured by this excerpt from Weber’s book about Davis’ ongoing Vegas experiences.

“Although many sources say Sammy Davis Jr. first performed in Las Vegas in 1944, evidence shows that his first visit to the city was in 1947 as part of the Will Mastin Trio. They performed at El Rancho Vegas, the first major resort on the Strip, and made a repeat visit in 1949. Given the racial restrictions of the time,they were not allowed to stay at the hotel or even watch other performers and had to stay at a boarding house in the Westside (map 4.11). In 1951 and 1952, the Trio played the Flamingo before switching to the Last Frontier in 1954. By this time Davis was a major performer and had enough clout to be allowed to stay at the hotel, one of the few Black entertainers given that privilege in those years.”

Weber continues……

“It was while driving back to Los Angeles from one of his Last Frontier performances that he had a car accident in San Bernardino, California, which cost him an eye. In 1957 Davis switched to the Sands, where he continued to perform regularly for the next seventeen years, recording That's All, a live album,in 1966. In 1974 he left the Sands for Caesars Palace, switching to the Aladdin in 1983 and finally in 198, to the Desert Inn. He died in 1990.”

Over time, Black entertainers began to assert themselves by refusing to perform without assurances of appropriate hotel accommodations as well as access to their audiences after the shows. In the early 1960’s Las Vegas NAACP Chapter President James McMillan threatened a citywide protest unless the city agreed to desegregate within thirty days of his announcement. This move eventually led to what became known as the Moulin Rouge Agreement which allowed Black Americans to have access to gambling activities, stay at the various Vegas resorts, and to attend shows.

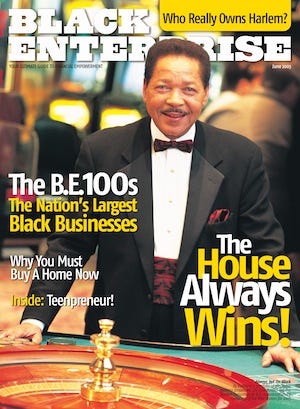

Don Barden

Back in 2017 during my earlier move to Las Vegas, I met a Black bellhop at the D Hotel who gave me my first inside scoop on Fremont Street, the original Vegas strip. He mentioned that The D as it is affectionately known had been owned by a Black business mogul by the name of Don Barden who purchased the property along with the two other Fitzgeralds which had been in bankruptcy.

In 2002 with this acquisition, Barden became the first Black American to open a casino in Las Vegas. With this achievement he became a trailblazer in the American gaming industry by breaking down racial barriers, paving the way for other Black Americans in the industry.

It goes without saying that I’m excited about moving back to Las Vegas and the opportunity to unearth more of its Black history over the course of my time there.

An Invitation from Diamond-Michael Scott

“Black Books, Black Minds” is a key foundation of my Great Books, Great Minds” passion project. For me, it’s a labor of love fueled by the endless hours of work I put into researching and writing these feature articles. My aim is to ignite a new world of community, connection, and belongingness through the rich trove of Black History books, thought leaders, and noted authors

So if you are enjoying this digital newsletter, find it valuable, and savor world-class book experience featuring non-fiction authors and book evangelists on Black History themes, then please consider becoming a paid member supporter at $6.00/month or $60.00/year.

Thank you. In the meantime stay thirsty for a great book