By Contributing Reviewer Marc S. Friedman

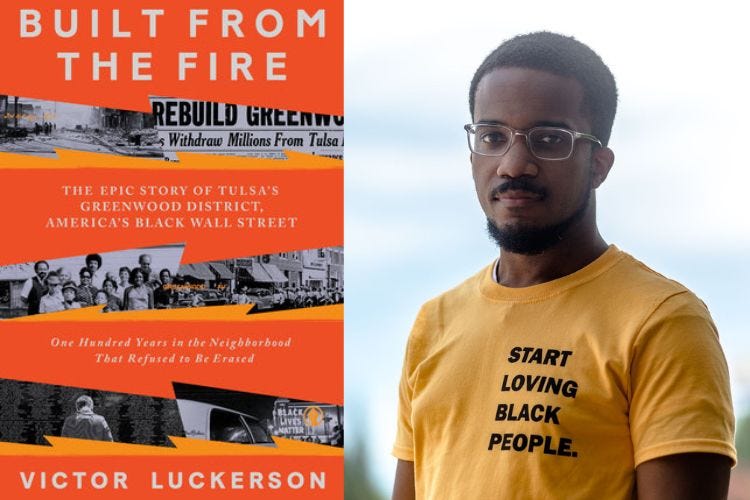

“Built From the Fire: The Epic Story of Tulsa’s Greenwood District, America’s Black Wall Street” by Victor Lukerson is an emotionally-charged and profoundly moving account of the infamous Greenwood Massacre of 1923 and the extraordinary journey of resilience, community, and healing that followed.

Written with a delicate yet unflinching touch, this book delves into the depths of tragedy while illuminating the indomitable human spirit.

The narrative is skillfully woven, seamlessly shifting between the horrific events of the Greenwood Massacre and the subsequent efforts to rebuild shattered lives and a fractured community. The author, with an empathetic pen, captures the rawness of the survivors' experiences, painting vivid portraits of their pain, courage, and determination.

After the Civil War, and as a result of Jim Crow laws throughout the South, many free Black Americans, known as “Freedmen”, moved from distant places to the Greenwood District in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

Not only did Tulsa appear to be welcoming, it appeared to many to be a place where Freedmen could live and thrive, where they could raise families in an atmosphere of tolerance, and where Black entrepreneurs would have an opportunity to build successful businesses.

Largely speaking all these dreams were realized by Freedmen. Greenwood became known nationally as the Black Wall Street.

On November 16, 1907, shortly after Oklahoma gained statehood, the state legislature passed a raft of Jim Crow laws that began to make life increasingly difficult for Oklahoma’s Black citizenry, including the inhabitants of Greenwood. Before statehood, Oklahoma represented tolerance toward Blacks. After statehood racial segregation was the goal.

By 1916, the resentment of many White Tulsa citizens toward the Greenwood District and its Black residents was growing. Greenwood’s businesses were enjoying great success. Residents were starting to leave Greenwood and move into White neighborhoods.

In August 1916, Tulsa’s all White governing body passed an ordinance prohibiting Black people from living in predominantly White neighborhoods, unless they were servants or other domestic workers in White homes.

World War One brought a sea change to America and, particularly, the South. Black soldiers who had fought for America in Europe, had experienced racial equality and acceptance overseas. When they returned home, they quickly saw that the South treated its Black population quite differently. Many Black leaders were determined to achieve racial equality and full citizenship in the South.

This created profound tensions. “Red Summer” was a period in mid-1919 during which White supremacist terrorism and racial riots occurred in more than three dozen cities across the United States. The phrase was coined by civil rights activist and author James Weldon Johnson, who, in 1919, organized peaceful protests against racial violence. Red Summer resulted in hundreds of deaths of Black Americans.

Black people in Greenwood began to resist the Jim Crow laws of Oklahoma. They refused to give up their streetcar seats to White passengers. They would not leave the sidewalks to make room for White pedestrians. They challenged the police who were making arrests. Relations between the White and Black communities in Tulsa and Greenwood soon deteriorated.

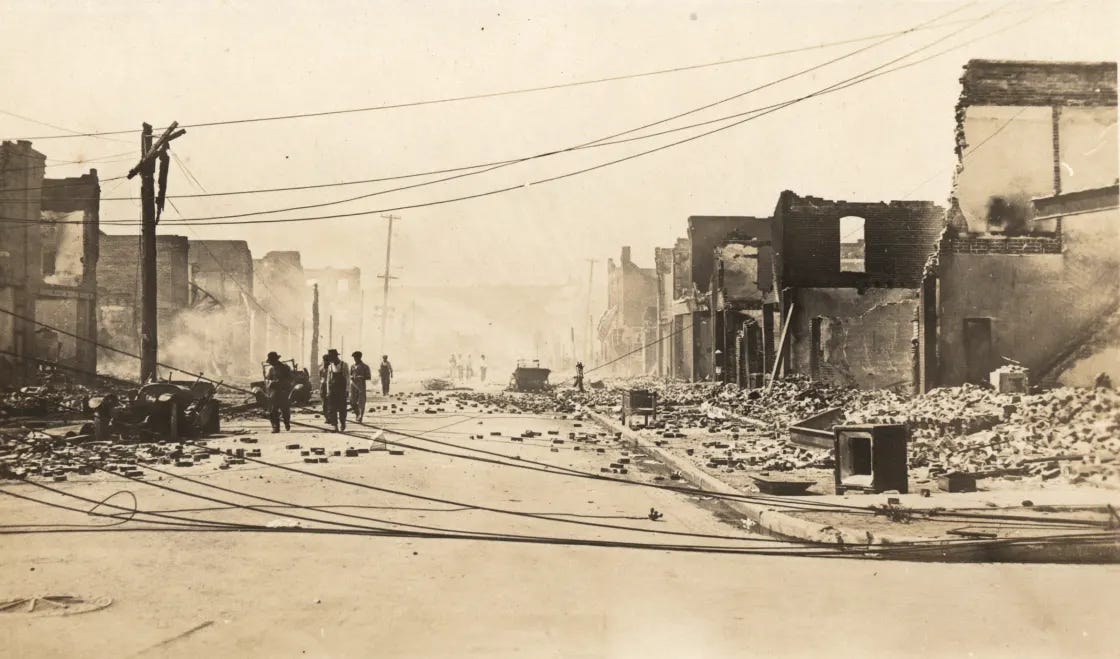

The situation boiled over on May 31, 1923. White Tulsans and other White racists from nearby towns attacked Greenwood and its residents. Hundreds of residents were killed, 1,250 homes were burned after being looted by Whites, and all businesses were destroyed. What took decades to build was erased in less than 24 hours.

The centerpiece of “Built From the Fire” is the Goodwin family that spanned several generations. Over the years following the massacre, members of the Goodwin family,together with others, battled on several different fronts -- with law enforcement, the White Tulsa community, insurance companies, greedy White land developers, racist courts, public opinion, and racist local and state governments. They not only sought justice for those victims of the Greenwood massacre.

They also were determined to rebuild Greenwood to be the welcoming and enriching neighborhood for Blacks that had existed before it was leveled. They were not always successful. But the Goodwins and their Greenwood allies never gave up. They were indefatigable.

What sets this book apart is its unyielding focus on the human capacity for hope and transformation in the face of unimaginable adversity. The author masterfully portrays the resilience of individuals like the Goodwins and others, the strength of community bonds, and the power of collective action.

Through the stories of survivors and the tireless efforts of those who rallied around them, the reader witnesses the unfinished process of healing and regeneration.

There are several examples of the fruits of these efforts. The historical Vernon AME Church, the only building in Greenwood still standing, has been restored. As one walks the neighborhood, there are many memorials marking important historical locations of businesses and homes that were burned to the ground.

Perhaps most significantly, the investigation of the massacre is continuing. Hopefully more unmarked graves can be located and more victims can be identified.

The characters are brought to life with nuance and depth, allowing the reader to forge a deep emotional connection. Many emerge not just as victims but as symbols of unbreakable spirit, beacons of hope that guide the community toward a brighter future.

The supporting cast of survivors, activists, and volunteers are equally compelling, showcasing the myriad ways in which ordinary individuals can become extraordinary forces for positive change.

Lukerson’s meticulous research and attention to detail are evident throughout the book, lending credibility and authenticity to the story.

For almost 100 years the City of Tulsa tried to bury the history and memories of the Greenwood Massacre. However, as the massacre’s 100th anniversary approached, many Tulsans, including White community leaders and major corporations, recognized the need to unbury the massacre.

The commemoration took place in a variety of ways including the establishment of a museum in Greenwood which tells the story of the death and rebirth of Greenwood. While Greenwood is not nor will it ever again be the “Black Wall Street”, it has already regained prominence as a destination site.

The history of the Greenwood Massacre is not just Black history. It was emblematic of other racial massacres occurring in the early 1920’s in cities, towns and villages across America. The Greenwood Massacre is part of American history. The event should not be forgotten lest it someday be repeated.

If you found value in this book review you may also like……….

I was just there! I bought Magic City by Jewell Parker Rhodes at a bookstore next to Greenwood Rising and can't wait to start reading

It would be helpful to know the role played by Marc S. Friedman in the review of this book.