How I Discovered Washington D.C Historical Figure Alethia Tanner

….and What I Learned About Her.

Joe William Trotter Jr.’s Building the Black City: The Transformation of American Life is more than just a sweeping historical work—it’s a reframing of how we see the making of America.

It doesn’t tell the story of cities through steel, capital, or towering skyscrapers. Instead, the book explores the hands, hearts, and hard-earned lives of African Americans—especially the Black poor—who built, sustained, and transformed American cities even as they were excluded from the very wealth they generated.

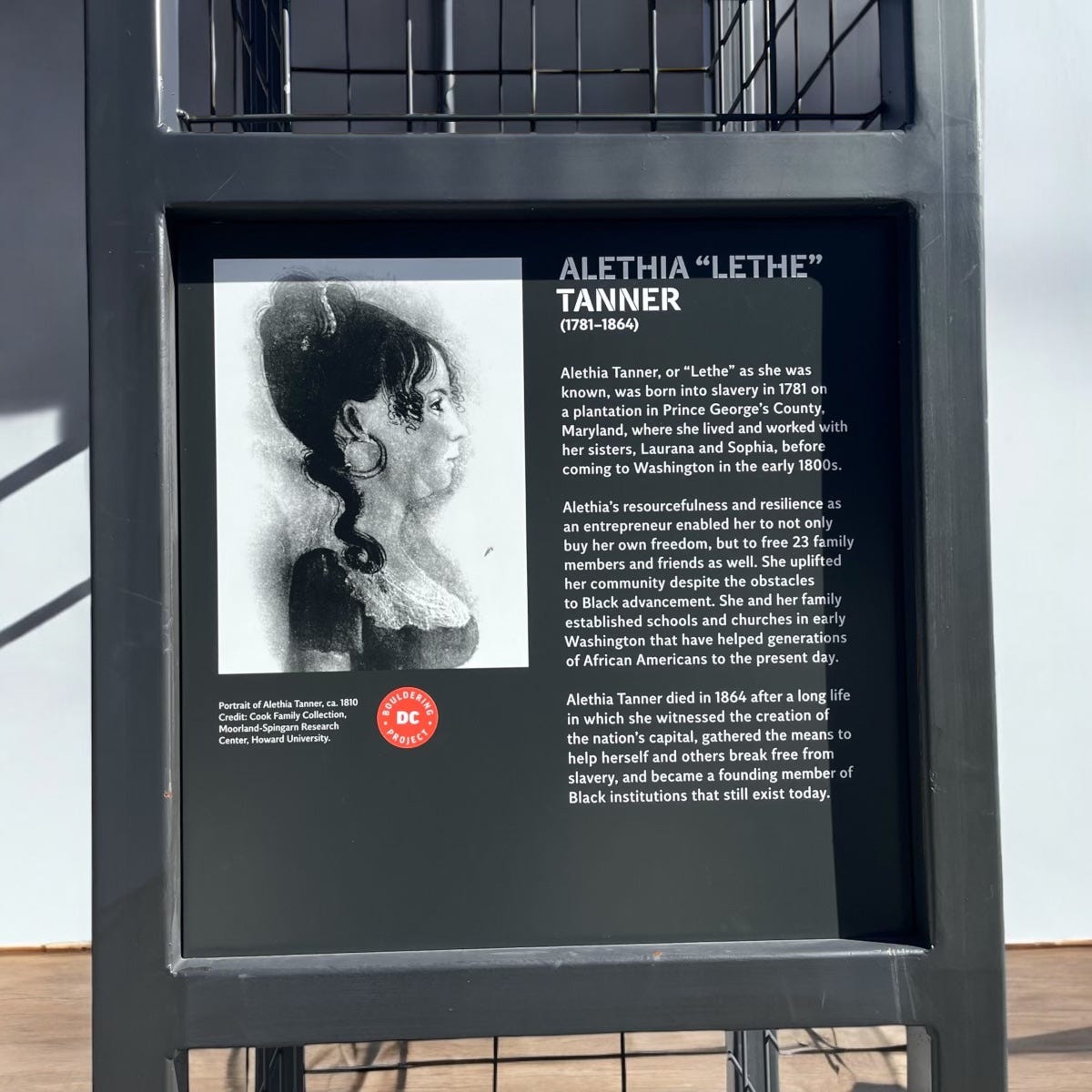

As I made my way through the pages of Trotter’s book, I stumbled across a figure I had never fully encountered in history books or classrooms. Enter Alethia Browning Tanner, a woman whose quiet dignity and determined action shaped the very soul of early Washington, D.C.

Alethia Tanner’s name did not shout from textbooks, but her legacy speaks in volumes to what Trotter calls “the Black city”—not merely a physical place, but a spiritual, socioeconomic, and cultural force that asserted itself amid systems of oppression. Tanner embodied this vision long before the term existed.

Born enslaved in 1781 on a Maryland plantation, Alethia’s life could have remained in the footnotes of history, buried beneath cotton yields and plantation accounts. But she rewrote her own fate—and in doing so, began rewriting the narrative of Black American power in the nation’s capital.

As a young woman, she sold vegetables grown on a small plot she and her sister cultivated. Her produce stand near the White House became more than a marketplace—it was an incubator of freedom. This space, just steps from the seat of American power, enabled her to earn enough to buy her own freedom in 1810, at a time when such an act was rare, bold, and dangerous.

The courage of that act would be enough to secure her place in history. But Alethia Tanner didn’t stop at liberating herself. Over the next three decades, she used her earnings, intelligence, and heart to purchase the freedom of more than 20 family members and neighbors. She didn’t just free bodies; she restored families—a quiet revolution in a society built on the systematic fracturing of Black kinship.

And this is where Trotter’s thesis lives and breathes in her life. The “Black city,” in his telling, is born not just in architecture or politics but in these kinds of determined, everyday acts of solidarity and resilience. Tanner’s story is a cornerstone of that city, showing us that Black civic life wasn’t a byproduct of emancipation—it was always present, always building.

What struck me most, though, wasn’t just what she did, but how she did it—with strategic brilliance, spiritual conviction, and community foresight. She invested not only in people’s freedom but also in their education. She ensured her nephew, John F. Cook Sr., had access to schooling—a radical act of vision.

He would grow up to become one of Washington’s most influential Black educators and pastors, and his descendants would continue shaping public education for decades. Her belief in education as a liberatory force stands as a testament to a deeper understanding: that freedom without knowledge is fragile.

Tanner also helped found the first school for Black children in the city in 1807—years before she was even legally free. Later, she helped sustain Black churches like Israel Bethel AME and Union Bethel, spiritual anchors for a community navigating freedom, faith, and resistance.

These were not merely places of worship but centers of political action, moral courage, and social organizing. Tanner, known affectionately as “the mother of the church,” lent not only money and land, but leadership and vision to these efforts.

We often think of American political history in terms of grand speeches and legislative halls. But Alethia Tanner’s life reminds me that Black political power often shows up first in kitchens, church pews, and street markets. Her produce stand near the White House may have been more influential to the shaping of American values than many halls of Congress.

Reading her story, I was flooded with a mix of emotions. Admiration, yes, but also a quiet grief. How many Alethia Tanners lived, fought, loved, built—and were forgotten by mainstream history? And what do we lose as a nation when we fail to honor them?

That’s why Trotter’s Building the Black City is such a vital intervention. It doesn’t ask us simply to reinsert Black people into the history of American cities. It demands that we center them.

It asks us to view urban development not just as policy and industry, but as the unfolding of Black aspirations, creativity, and resistance. Alethia Tanner’s life story becomes a masterclass in how Black America didn’t wait for freedom to be handed down from on high—they built it, one family, one school, one congregation at a time.

In 2020, Washington, D.C., took a meaningful step in correcting the historical record by naming a public space Alethia Tanner Park, just miles from where she once walked.

But I would argue that the true monument to her legacy isn’t found in brick and mortar. It’s found in the generations of free, educated, spiritually grounded Black Americans who followed in her wake—many of whom didn’t know her name but lived the fruits of her labor.

Alethia Tanner showed us what it means to transform a city not through conquest, but through care. She saw freedom not as an individual prize but as a communal responsibility. Her life asks us, across time and distance, a question that still resonates: What are we doing with our freedom today to liberate those who come after us?

To me, discovering Alethia Tanner through Trotter’s work wasn’t just a historical footnote—it was a personal awakening. It reframed how I understand Black resistance, Black ingenuity, and Black love. She didn’t just live in the shadow of the White House; she cast her own light.

And in remembering her, we remember that the foundation of every American city worth celebrating was laid not just in concrete and commerce—but in the uncompromising belief that every human being deserves to be free, educated, and whole.

If you are finding “Black Black, Black Minds” to be a valuable resource in learning about Black History , then please consider supporting my work by subscribing as a paid member or tipping me some dirty chai latte love.

No paywalls—just raw, well-researched feature articles delivered straight to your inbox. Every contribution helps keep this journey alive. you contributions will be greatly appreciated.

Diamond Michael Scott, Global Book Ambassador

Her story is a recognition of the fact that D.C. has long been a haven for Black activity and commerce in the areas far away from the seats of white power.