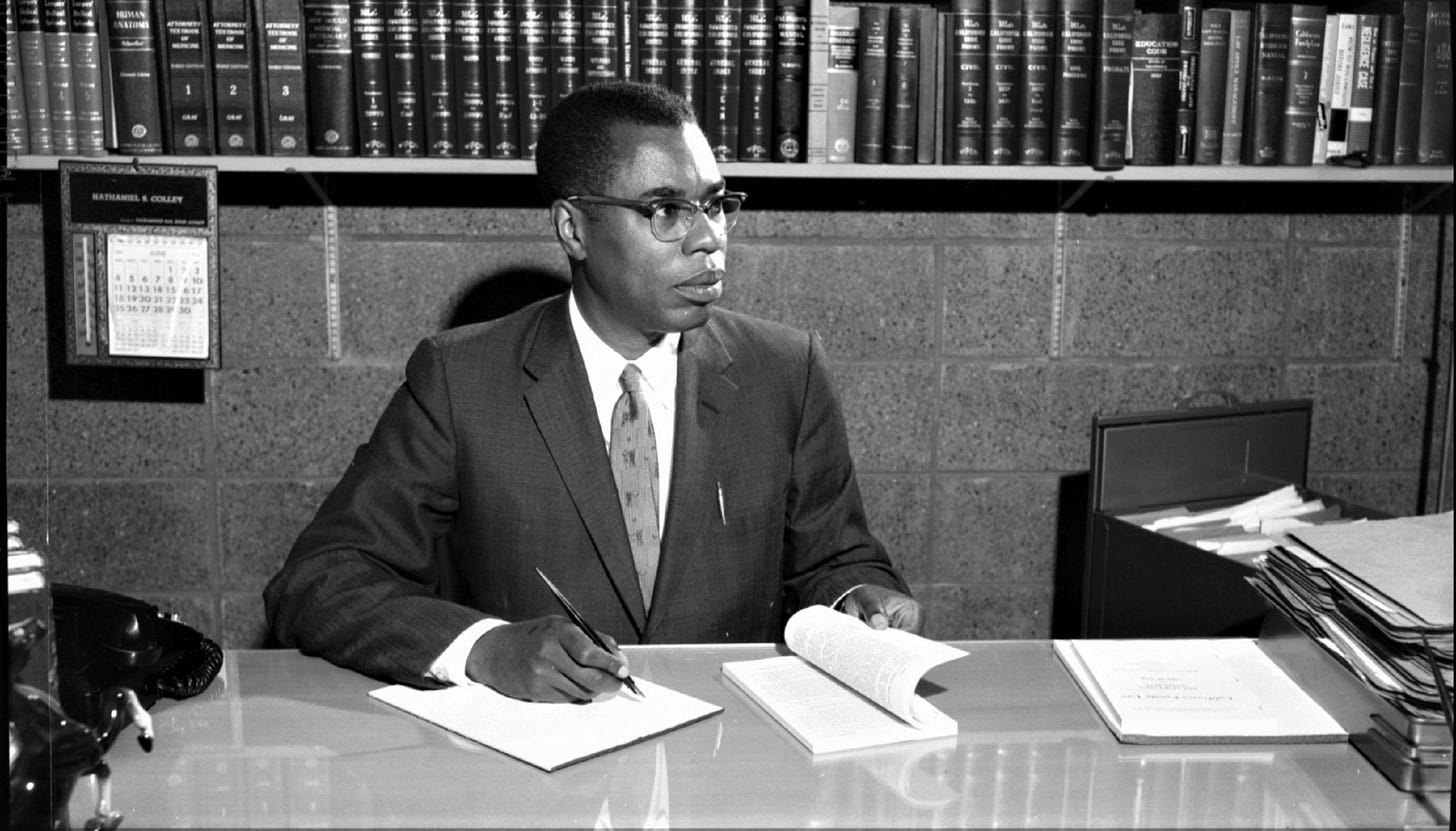

Nathaniel Colley and His Tireless Advocacy for Racial Justice

From 2003 through 2010 during a pivotal period in my life, I resided in the Sacramento (California) area. Married at the time with a one year old child, we moved there to be of support to my father-in-law who was diagnosed with Parkinson’s.

The city which is California’s state capital was going through its own evolution at the time, including electing its first Black mayor, Kevin Johnson in 2008. And in an interesting aside, the Civil Rights Project at Harvard University conducted for TIME magazine named Sacramento “America's Most Diverse City in 2002.

Sadly, during my time there, I was unable to delve into the Black historical legacy of the city. Recently though while researching a new article I was writing on Sacramento’s Black history, I stumbled upon the name of Nathaniel Colley. So I decided to take a moment to do a deep dive into this prominent Sacramento figure and his tireless advocacy for justice.

Nathaniel Colley, who is widely regarded as Sacramento’s first private-practice Black attorney, was a prominent advocate and crusader for racial justice and civil rights. His work led him to rub shoulders with prominent leaders such as John F. Kennedy, Lyndon Johnson, Rosa Parks, Edmund “Pat” Brown, Joseph Biden and Bill Clinton.

Colley was born on November 21, 1918 in Carlowsville, Alabama, the youngest of six brothers, He was raised in Snow Hill, Alabama, and graduated from the historically black college Tuskegee Institute in 1941. Colley was later rejected by the University of Alabama Law School because he was Black. He later earned his law degree from Yale University, graduating with honors in 1948.

In 1948, Colley relocated to the Sacramento area to become a trial attorney. During this time he developed a passionate interest in civil rights issues, serving on the legal committee of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and as their western regional legal counsel.

According to William Burg, author of the book Sacramento’s Renaissance: Art, Music, and Activism in California’s Capital City Colley and the Sacramento NAACP became a political force in Sacramento, advocating for the area’s growing Black professional and business class, cultural institutions, and aims to extend their community outside the prevailing boundaries of Sacramento’s West End.

Colley, however, might best be known for his legal work with discrimination cases. In 1949, he began by representing Albert Bacon, a tile setter who was banned from the union despite his wanting to join. Bacon then attempted to take matters in his own hands by working as a tile setter, a move which created rancor and worksite picketing among the union membership. The judge later ruled that the union had the authority as a private organization to deny Bacon’s union membership.

Colley filed an appeal based on a previous California Supreme Court case, James v. Marinship, which prohibited union business monopolies restricting membership due to race. While awaiting appeal, Colley advised Bacon to pursue work as a contractor. Over the course of a few years, Bacon launched his own tile business, hiring on a number of the same union members who had stubbornly voted to refuse him.

It was also during this period that Colley provided successful representation to two young men who were brutally beaten by law enforcement into confessions, successfully winning a lawsuit against the police officers and the city.

During the 1950s, Colley pursued a court case to integrate the Land Park Plunge, a public swimming pool that was privately owned on Riverside Boulevard across from Land Park. Blacks were prohibited from using the pool, leading to a saying among Sacramentans at the time that “if you had a suntan, you could not get into the Plunge.” Colley prevailed in the court case, leading to a settlement for the plaintiff, Hazel Jackson. Shortly thereafter the Land Park Plunge suspiciously closed with Colley noting:

“I think the integration of the pool caused it to go out of business…I think they’d rather not operate it than have to operate it on a desegregated basis.”

In another legal case in 1952, Colley received a ruling from the Sacramento County Superior Court that forbade segregation by the Sacramento Housing Authority. Then in the 1957 ruling Ming v. Horgan, Colley led the push to prohibit developers who received Federal Housing Administration and Veterans Administration funding from engaging in discrimination.

Then there was the landmark California case in 1964 tied to proposition 14 that gave property owners the right to refuse to sell their property to anyone while barring the state and local governments from enacting fair housing laws. Colley and his legal team successfully argued to the California Supreme Court that this initiative violated the Fourteenth Amendment equal protection under the law clause. Proposition 14 was then voided in 1966 with the United States Supreme Court upholding the decision the following year.

Colley was also a staunch advocate for employment and education issues. He served as co-chair of the California Committee for Fair Employment Practices, helping to secure the California Fair Employment Practices Act in 1959, which prohibited discrimination in the workplace.

In 1960, Governor Edmund G. “Pat” Brown appointed Colley to the California State Board of Education, giving Colley the distinction of being the first Black American on the board. While in this role Colley strongly denounced the neglect of Black History in textbooks, encouraging book publishers to give sufficient coverage of the legacy and key contributions of Black Americans in U.S. history. He also created regulations that were adopted by the school board which fueled the end of discrimination in several California school districts.

During those years, Colley also was a part time instructor at McGeorge School of Law at the University of the Pacific in Sacramento. While there he taught alongside Professor Anthony M. Kennedy, who he was close friends with during the 70s and 80s. When president Ronald Reagan nominated Kennedy to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1987, Colley testified on Kennedy’s behalf at the Senate Judiciary Committee hearings. The Senate later approved Kennedy’s nomination.

In later years, Colley admitted to having regrets for his endorsement given Kennedy’s conservative views on civil rights. “I wish I could take back that endorsement,” he told the Los Angeles Daily Journal, a legal newspaper, a couple of years later.

On May 20, 1992 Nathaniel Colley died at his home in Elk Grove, California. He was 74.