Would you be kind enough to consider becoming a “Black Books, Black Minds” member supporter? At $6.00/month or $60.00 year, your funds will help me sustain this labor of love and deliver great Black History content to you. Thank you!

There’s something about New Orleans that reaches deep into my heart—a rhythm, a pulse, a heartbeat. Walking its streets, you can't help but feel the vibrations of history, the echoes of a city that has seen the best and the worst of times, yet somehow always dances through them.

My visits to New Orleans have been a pilgrimage of sorts, each time drawn to the music that seems to emanate from every corner, every hidden alleyway. Jazz, blues, and the sounds of horns blend seamlessly with the laughter and shouts of life in a city that never forgets its roots.

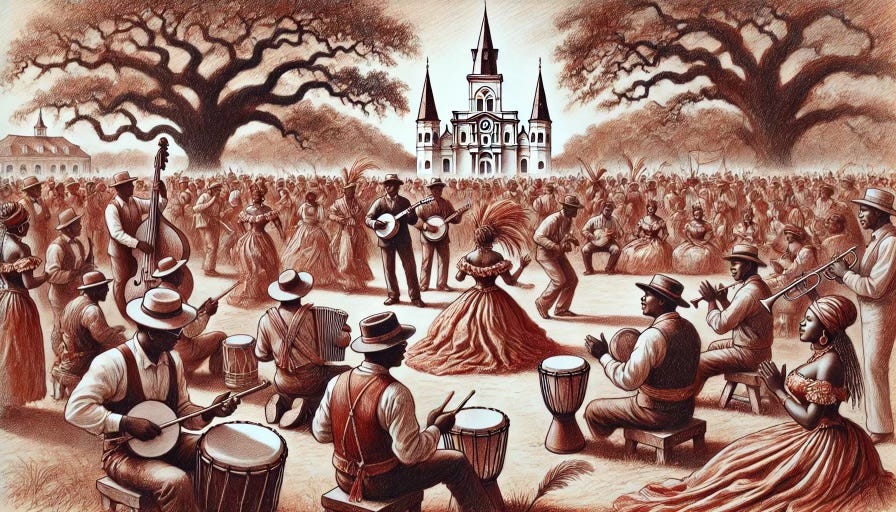

I believe there’s no place in New Orleans that’s more emblematic of this iconic vibe than the historic Congo Square, a sacred ground in the cradle of Black musical history.

While reading the book “Dangerous Rhythms: Jazz and the Underworld” the other night, I found myself captivated by how the author T.J. English peels back the layers of jazz history to reveal a lesser-known symbiosis between the music and organized crime.

The book sheds light on a complex, often exploitative relationship that allowed jazz to flourish in some of the most notorious vice districts of America. What struck me most, however, was how this history is deeply intertwined with the Black musical legacy that began in places like Congo Square in New Orleans—a place I've come to reflect on often.

Congo Square, now nestled within Louis Armstrong Park, is more than just a patch of land in New Orleans. It is a testament to the power of music and cultural resilience. Dating back to the 18th century, this was where enslaved Africans, on Sundays—their only day off—gathered to dance, drum, sing, and remember.

As English noted in his book:

“On Sundays in what was once known as Congo Square (now part of Louis Armstrong Park), Blacks gathered to play the drums, chant, sing, and dance. These gatherings involved a near direct transference of rhythm patterns and dance movements from Africa, where rhythmic music has always been as much a spiritual undertaking as a social one. This tradition of drum circles in Congo Square continued throughout much of the nineteenth century, right up until the birth of jazz as the city's popular musical form. The renowned Creole reed player Sidney Bechet, born in New Orleans in 1897, eventually found fame and a livelihood on a world stage, but he never forgot his roots.”

In the midst of their bondage, Congo Square became a sanctuary for expression, a place where they could keep alive their cultural heritage and forge a new musical language that would eventually give birth to jazz.

The sounds of the Bamboula, Calinda, and Congo dances, the syncopated rhythms of drums and gourds—these were the heartbeats that pulsed through New Orleans and into the bloodstream of America.

I remember my first visit to Congo Square. It was a hot, humid day, and the air was thick with the smell of magnolia and earth. There wasn’t much to see, just an open space surrounded by trees, but I felt the weight of history there, as if the ground itself was still vibrating with the rhythms of those who danced long ago.

At that very moment I understood that Congo Square wasn’t just a historical site; it was a living, breathing archive of Black music and culture, a place that bore witness to the resilience and ingenuity of enslaved Africans who turned suffering into something transcendent. The sounds that arose from Congo Square were not just music; they were acts of defiance, creativity, and ultimately, freedom.

In “Dangerous Rhythms,” English recounts how jazz, born from these African rhythms and musical traditions, found itself intertwined with the underbelly of American society. From the smoky clubs of Storyville in New Orleans to the nightclubs of Chicago and New York, mobsters like Al Capone, Meyer Lansky, and Lucky Luciano controlled the venues where jazz musicians, mostly Black, played to make a living.

It was a complicated dance between exploitation and opportunity. On the one hand, the mob provided platforms for jazz artists like Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, and Billie Holiday to shine in ways that might not have been possible otherwise. On the other hand, there were strings attached, a glorified plantation system where Black artists were often at the mercy of white gangsters who controlled the clubs, the bookings, and, unfortunately, the means of production.

Reflecting on this history, I think of the countless times I've wandered through New Orleans, listening to street musicians on Royal Street or in Jackson Square. Their music—a mélange of brass, blues, and gospel—carries with it the unmistakable imprint of Congo Square.

For me it’s a reminder that what began there was not just a form of entertainment but a powerful legacy of cultural resistance. Jazz, in all its complexity, is a music born from the tension between oppression and freedom, much like the tension that exists in the pages of English's narrative.

Congo Square was, and still remains, a symbol of this duality—a place where joy could rise out of suffering. As English points out, the rhythms of jazz carried this duality forward, reaching into the smoke-filled, mob-controlled clubs of the 20th century, where the music often masked darker realities.

Says English in his book:

“Thus, in New Orleans, music and slave commerce were inexorably in-tertwined; the ground on which the roots of jazz found fertile soil was also a locale of capitalist exploitation and sorrow. Eventually, this bitter reality would become the emotional foundation of the blues, another musical form whose folkloric impetus comes from the African continent.”

For many Black musicians, playing in these venues meant navigating a treacherous path between artistic expression and survival in a world that devalued both their humanity and their art. Some, like Louis Armstrong, believed that working in “protected” joints controlled by the mob provided safety and ensured they were paid fairly. Others saw it as another form of exploitation, fighting to play in venues outside mob rule to gain more control over their careers and their lives.

This dynamic wasn’t new; it was a continuation of the historical struggle of Black artists to assert autonomy in spaces that sought to control and commodify their creativity. Yet, through it all, the spirit of Congo Square endured. It is a space that has continued to inspire, not just in jazz but in every iteration of Black music that followed—blues, rhythm and blues, rock and roll, hip-hop. The heartbeat that started there continues to echo through the ages.

Whenever I return to New Orleans, I am reminded of the rich mosaic of stories, struggles, and rhythms that define this city. From the cobblestone streets of the French Quarter to the moss-covered trees of Congo Square, the music speaks of an indomitable spirit. In “Dangerous Rhythms,” T.J. English gives us a glimpse into the darker side of this history, but he also underscores the incredible power of jazz as a force of cultural expression and resistance.

New Orleans will forever be the birthplace of jazz, not just because of the notes and melodies that were created here, but because of the spirit of those who refused to be silenced. Congo Square remains a powerful symbol of that spirit, a reminder that even in the face of unimaginable hardship, we can find a rhythm that carries us forward, a dangerous rhythm that defies oppression and dances toward freedom.

Hi! Thank you for your article. Can I ask where you sourced the first image? I've tried to reverse search the image and can't find it anywhere but it's beautiful.

This is one location I would love to visit New Orleans. "Congo Square" sounds like a great name, I assume in reference to the French speaking location in central Africa, where many were shipped from to America and especially the Caribbean islands in the slave trade. Great read!