Would you be kind enough to consider becoming a “Black Books, Black Minds” member supporter? At $6.00/month or $60.00 year, your funds will help me sustain this labor of love and deliver great Black History content to you. Thank you!

In the Buckeye State where I hail from, Oberlin, Ohio stands as a testament to the relentless pursuit of freedom and justice that defined the American abolitionist movement.

Founded in 1833 by Presbyterian ministers John Shipherd and Philo P. Stewart, Oberlin was conceived as a community where Christian principles of equality and social activism could flourish.

Named after Jean-Frédéric Oberlin, a Lutheran clergyman known for his philanthropy, the town was destined to become a beacon for racial justice and educational reform.

The establishment of the Oberlin Collegiate Institute, later Oberlin College, on September 2, 1833, marked the beginning of a revolutionary chapter in the fight for racial and gender equality. From its inception, the college embodied the radical ideals of its founders, admitting students regardless of race or gender—an unprecedented stance in antebellum America.

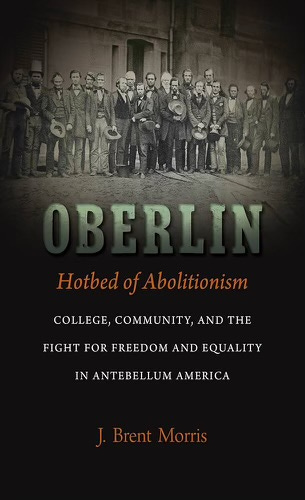

As J. Brent Morris eloquently chronicles in “Oberlin: Hotbed of Abolitionism,” the college’s “perfectionist Christianity” fostered the nation’s first multiracial, coeducational institution, creating an integrated community that defied the deeply entrenched norms of racial segregation and oppression.

Oberlin’s abolitionist zeal was fueled by individuals like William Dawes and John Keep, who, between 1839 and 1840, toured England garnering support from abolitionists. Their efforts made Oberlin an attractive sanctuary for aspiring Black students, as Morris notes, turning the college into the epicenter of the antislavery movement in the West.

Oberlin’s unique brand of antislavery activism was not bound by strict ideological constraints; rather, it was a pragmatic, inclusive movement that embraced various schools of thought, united by a shared commitment to emancipation.

By 1835, Oberlin College admitted its first Black students, Gideon Quarles and Charles Henry Langston, making it the first predominantly white institution in America to do so. Two years later, the college became the first to admit women, further solidifying its reputation as a revolutionary force for social change.

Oberlin’s abolitionist credentials were beyond reproach, with the town and college serving as a vital stop on the Underground Railroad. Morris captures this spirit of resistance, noting that “if you made it to Oberlin, you made it to freedom.” However, the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 loomed over the town, necessitating constant vigilance and action to protect those who sought refuge there.

The tension between Oberlin’s ideals and the harsh realities of American law culminated in the Oberlin-Wellington Rescue of 1858, a landmark event that Nat Brandt details in his book, “The Town That Started the Civil War.”

On September 13 of that year, federal slave catchers kidnapped John Price, a fugitive enslaved person, from nearby Wellington. In response, 600 Oberlin residents, Black and white alike, marched to Wellington, stormed the hotel where Price was held, and secured his safe passage back to Oberlin and eventually to Canada.

This daring act of defiance, supported by the community’s unwavering belief in justice, drew the ire of federal authorities. Thirty-seven members of the rescue party, including Charles Langston, were indicted for violating the Fugitive Slave Law.

Langston’s trial and subsequent conviction became a rallying point for the abolitionist cause. His impassioned speech in court, denouncing the institution of slavery and advocating for Black humanity, resonated so profoundly that the judge delivered a lighter sentence.

This moment, as Morris points out, was a catalyst for widespread protest throughout Northern Ohio, galvanizing support for the anti-slavery Republican Party in the 1860 elections. While Lincoln’s refusal to repeal the Fugitive Slave Act may have been a pragmatic choice to avoid further sectional strife, the events in Oberlin and beyond made it clear that the nation was on an inexorable path to civil war.

The legacy of Oberlin’s activism extended far beyond the antebellum period. By 1900, Oberlin College had produced one-third of all Black graduates in the United States, many of whom became prominent leaders in the struggle against segregation and discrimination.

John Mercer Langston, Charles Langston’s younger brother and an Oberlin graduate, became the first Black elected official to the U.S. Congress from Virginia in 1888. Oberlin’s commitment to social justice continued into the 20th century, playing a pivotal role in the Civil Rights Movement.

The college hosted a campus chapter of the NAACP, participated in sit-ins and boycotts in Cleveland, and welcomed leaders like Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., who was awarded an honorary degree for his contributions to the cause of justice.

J. Brent Morris’s work reminds us that Oberlin was more than just a hotbed of abolitionism; it was a crucible for the transformative ideas that would reshape the American conscience. The town and its college were not mere passive bystanders in the march toward freedom; they were active participants, pushing the boundaries of what was possible in a nation grappling with its original sin of slavery.

Oberlin’s story is not just a chapter in the history of abolitionism; it is a profound narrative of courage, conviction, and the enduring belief in the fundamental equality of all people. As we continue to grapple with the legacies of racism and injustice, Oberlin’s example serves as a beacon, illuminating the path toward a more just and equitable society.

Our Invitation to Join “Black Books + Black Minds.”

As a supporting member of "Black Books, Black Minds," you'll provide much needed resources for me to continue to dive deeper into a world where your reading passions around Black History thrive.

For just $6 a month or $60 a year, you unlock exclusive access to a close-knit community eager to explore groundbreaking authors and books.

So join us today. Your participation and support are welcomed and appreciated.

My students begin reading Beloved next month.