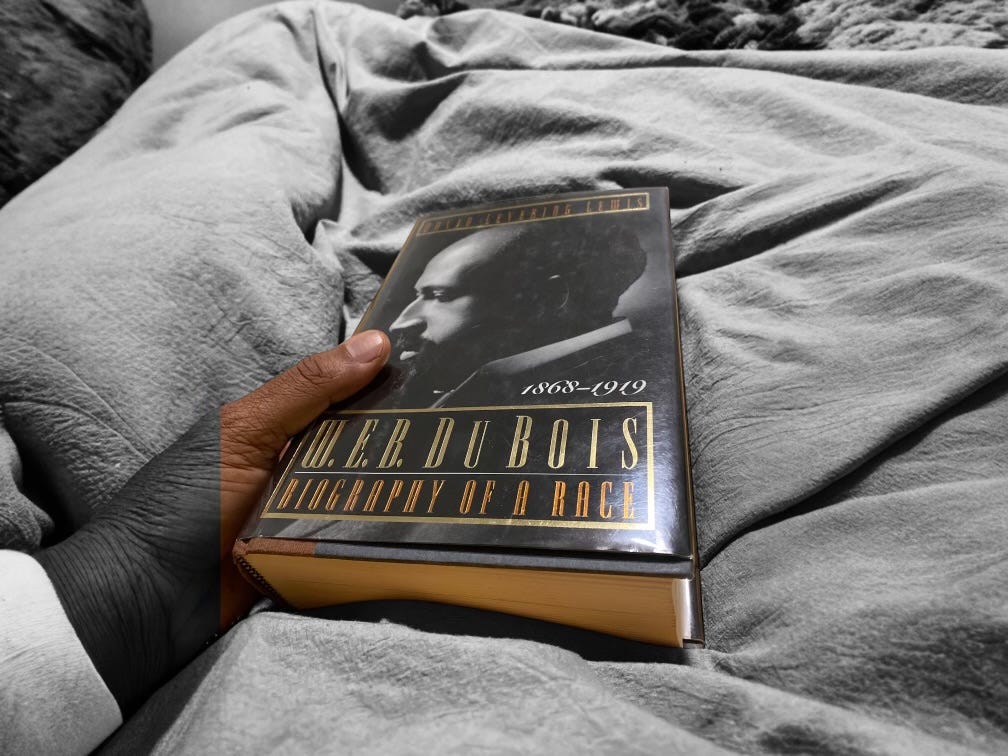

I first stumbled upon the John F. Slater Fund while reading W.E.B. Du Bois: Biography of a Race by David Levering Lewis.

The passage that introduced me to this philanthropic initiative described how a persistent young Du Bois wrote letters and eventually secured a $750 fellowship to study at Friedrich Wilhelm University in Berlin. That sum, structured as half loan and half gift, transformed his academic journey.

Intrigued, I delved deeper into the history of the Slater Fund and its impact, discovering a profound story of vision, contradiction, and resilience woven into the fabric of Black educational advancement.

In an excerpt from the book, Lewis writes:

“Handed a Boston Herald clipping dated November 2, 1890, Du Bois read that the president of the John F. Slater Fund for the Education of Negroes had offered to underwrite the European education of "any young colored man in the South whom we find to have a talent for art or literature." In a speech at Johns Hopkins University, Rutherford B. Hayes, the president who had dismantled Reconstruction and now presided over the million-dollar Slater benefaction, had added that it was very doubtful such a Negro existed. "Hitherto," said Hayes (in what was surely a dismissive reference to Du Boiss friend Morgan), "their chief and almost only gift has been that of oratory." Du Bois had rushed at the challenge; "No thought of modest hesitation occurred to me." Two days after the Herald story appeared, he sent a detailed letter announcing that he was just what the Slater Fund was looking for. That he would also be leaving Maud Cuney behind, if the fund eventually recognized his claim, was the bittersweet price of destiny.”

Established in 1882 by Connecticut textile magnate John F. Slater, the fund began with an extraordinary $1 million endowment—an amount that, in today’s terms, would be worth tens of millions.

The fund’s aim was clear: to support the education of freed African Americans in the post-Civil War South. Yet, beneath this clarity lay a complex interplay of paternalism, pragmatism, and progressivism that shaped its impact for decades.

Industrial Education and the Early Years

In its infancy, the Slater Fund aligned with the prevailing ideology of the time, championed by Booker T. Washington, which emphasized industrial and vocational education.

This approach, designed to provide immediate economic opportunities, often clashed with the broader intellectual ambitions of Black Americans, who yearned for access to classical and liberal arts education.

Despite this tension, the fund succeeded in expanding access to institutions like Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute, Tuskegee Institute, and Spelman Seminary.

By 1931, the Slater Fund had distributed over $2.2 million—a staggering figure—to uplift a population systematically disenfranchised by segregation and underfunded public education.

Du Bois and the Power of Persistence

Enter W.E.B. Du Bois, a scholar whose aspirations transcended the boundaries of industrial education. His story, as told by Lewis, illuminates the complexities of funding Black intellectual pursuits in an era when such aspirations were often deemed audacious.

Du Bois’s initial rejection by the Slater Fund highlights the narrow vision that sometimes guided its decisions. But his dogged determination—writing multiple letters and arguing his case—demonstrated the power of advocacy.

When the fund eventually granted him the fellowship, it set the stage for one of the most transformative periods of his life. In Berlin, Du Bois encountered a society where, as he later wrote, he was “treated as a human being.” This experience profoundly shaped his worldview and his lifelong commitment to the struggle for racial equality.

The Slater Fund’s support of Du Bois, albeit reluctantly, underscores its potential to elevate Black leadership and intellectualism beyond vocational confines.

The Broader Impact of the Slater Fund

The Slater Fund’s legacy extends far beyond Du Bois. Institutions like Fisk University and Claflin University received critical financial support, allowing them to train generations of Black teachers and leaders.

This focus on teacher training was particularly impactful, as it created a ripple effect that empowered entire communities through education.

The fund’s contributions to public education, though limited, were equally significant. By providing resources to Southern urban school boards and state normal schools for African Americans, the Slater Fund helped to improve the quality of public schooling during a time when segregation and systemic neglect left Black students with few opportunities.

However, the fund’s emphasis on industrial education revealed its limitations. Critics, including Du Bois himself, argued that this focus reinforced racial hierarchies by channeling Black Americans into manual labor roles.

Yet even within these constraints, the fund played a vital role in sustaining educational infrastructure during an era of widespread hostility toward Black progress.

A New Chapter: The Southern Education Foundation

In 1932, the Slater Fund merged with other educational philanthropies to form the Southern Education Foundation (SEF). This consolidation marked the end of the fund’s independent operation but ensured its mission continued.

The SEF adopted a broader approach, supporting a range of educational initiatives that addressed the evolving needs of Black communities in the South.

Reflections on Funding and Black Advancement

The history of the Slater Fund offers valuable lessons about the importance of funding in advancing Black education. It underscores the necessity of not only providing resources but also recognizing and supporting the full spectrum of Black aspirations, from vocational training to intellectual pursuits.

Du Bois’s savvy in securing funding throughout his career exemplifies the critical role of persistence and strategic negotiation in overcoming institutional barriers.

His story reminds us that access to education—and the financial support that makes it possible—is not merely a pathway to individual achievement but a cornerstone of collective liberation.

Recommended Reading

If you find yourself interested in exploring the Slater Fund’s legacy further, I recommend the following books:

The John F. Slater Fund: A Nineteenth Century Affirmative Action for Negro Education by John E. Fisher offers a comprehensive analysis of the fund’s role in promoting Black education.

The Untitled Report by the John F. Slater Fund for the Education of Freedmen (1902) provides primary source insights into its operations and contributions.

W.E.B. Du Bois: Biography of a Race by David Levering Lewis not only sheds light on Du Bois’s connection to the Slater Fund but also situates it within the broader context of Black intellectual history.

The John F. Slater Fund was far from perfect, but its contributions to Black education in the late 19th and early 20th centuries were undeniable. It provided a lifeline to institutions and individuals who might otherwise have been excluded from the transformative power of education.

For figures like W.E.B. Du Bois, it was both a stepping stone and a symbol of the complexities of racial progress.

In revisiting this history, we are reminded that the fight for educational equity is ongoing. The story of the Slater Fund challenges us to think critically about the ways in which philanthropy can serve as both a tool for empowerment and a reflection of its time.

As we navigate our own era of racial and educational disparities, its lessons remain as relevant as ever.

We Invite You to Join “Black Books + Black Minds.”

As a supporting member of "Black Books, Black Minds," you'll provide much needed resources for me to continue to dive deeper into a world where your reading passions around Black History thrive.

For just $6 a month or $60 a year, you unlock exclusive access to a close-knit community eager to explore groundbreaking authors and books.

So join us today. Your participation and support are welcomed and appreciated.