“In Charleston, Mary Purvis became widely known as the city's "Oyster Woman." By 1860, Purvis had built viable business connections to the fishermen along the city's busy docks, thus securing a reliable and steady upply of oysters for her street business. Her success and that of other women and vendors underlay passage of recurring legislation to curb their "control over the city's food supply."

Building The Black City: The Transformation of American Life by Joe William Trotter Jr.

In the heart of antebellum Charleston, where cobblestone streets met the salt-tinged air of the Atlantic, a singular figure stood out among the bustling marketplace—a free Black woman named Mary Purvis, known to all as the city’s “oyster woman.”

Against the backdrop of a deeply segregated South, where opportunities for Black entrepreneurship were scarce and economic independence for Black women was almost unheard of, Purvis carved out a thriving enterprise in the seafood trade.

In researching this piece, I was struck by the fact that her success was not simply a matter of survival but a testament to her resilience, business acumen, and determination to claim her place in Charleston’s economy.

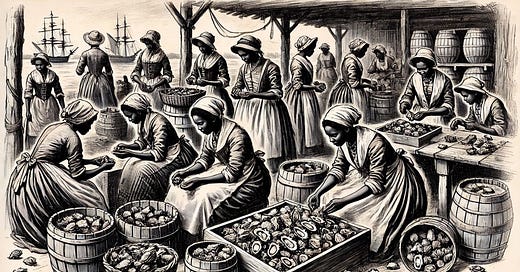

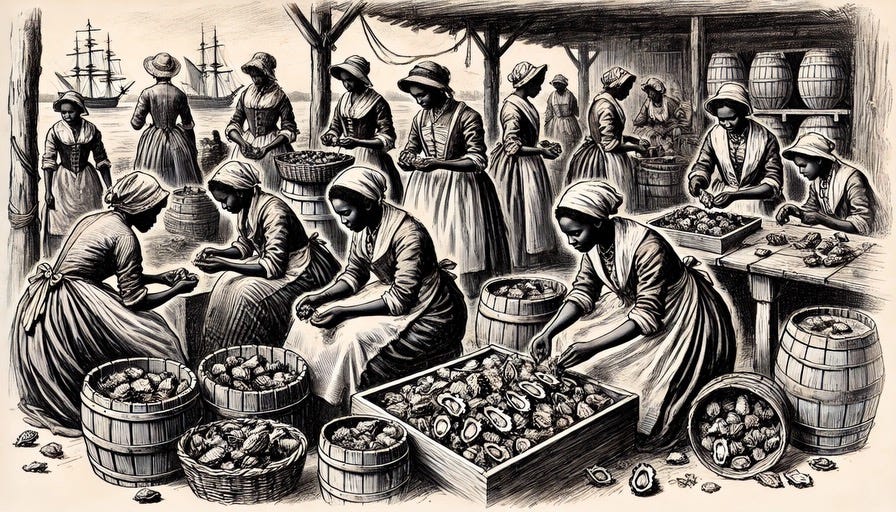

Despite racial and gender constraints that severely limited access to traditional business avenues, Black women like Purvis dominated the city’s food markets, particularly in seafood vending.

Their presence was deeply rooted in history—enslaved Black women had long been permitted to peddle fish, oysters, and crabs, sometimes keeping a portion of their earnings to purchase their freedom. Mary Purvis stood on the shoulders of this legacy, transforming what had once been a means of survival into an independent business.

By the mid-19th century, she had established herself as a premier oyster vendor, known throughout Charleston for the freshness of her catch and the sharpness of her entrepreneurial instincts.

The 1860 Charleston city directory listed Purvis as a “huckster,” a term used to describe independent street vendors who operated outside the formal market system. But Purvis was no mere street peddler — she had developed a sophisticated network of suppliers—likely local Black fishermen who harvested oysters from the city’s bountiful tidal waters.

She then took these oysters directly to the people, selling them at market squares, along the wharves, and through Charleston’s winding alleys, where her voice rang out as she called attention to her wares.

In an era when white Charlestonians largely viewed Black labor as subservient, Purvis’s economic independence was a quiet yet profound act of defiance. She was not beholden to an employer; she answered only to the rhythms of the sea and the demands of her customers.

Charleston’s economy was inextricably linked to its seafood trade, and Purvis played a crucial role in ensuring that its citizens—both Black and white—had access to fresh oysters daily.

The region’s love affair with oysters was well-documented; they were a staple of Southern cuisine, featured in stews, roasts, and raw on the half-shell. The success of Purvis and other Black seafood vendors helped sustain Charleston’s reputation as a culinary hub, providing restaurants and households alike with a steady supply of the ocean’s bounty.

More than just a businesswoman, Purvis was an early pioneer of a parallel food economy that thrived in the margins of segregation. Black women like her operated a robust, informal marketplace, serving both Black and white customers despite laws and customs that sought to limit their economic mobility.

These women became the backbone of Charleston’s local food distribution, and their presence was so pronounced that contemporary visitors often remarked on their dominance in the city’s street commerce.

A traveler once noted that the market squares and wharves were filled with “dozens of Black female vendors selling everything from fresh fruit and oysters to clothing and homemade crafts,” their cries for business forming an unmistakable soundscape of Charleston life.

The end of the Civil War only magnified the influence of Black women in Charleston’s seafood trade. Emancipation meant that formerly enslaved women could now fully engage in business without restriction, and many chose to remain in familiar trades such as seafood harvesting and vending.

The late 1860s and 1870s became a golden age for Black women entrepreneurs, with street corners lined with oyster and fish vendors, their baskets balanced expertly atop their heads.

As men focused on gathering the seafood, it was often the women who took on the retailing role, a dynamic that positioned them as key players in Charleston’s economic ecosystem.

Purvis, already well-established before the war, likely saw her business expand as more Black women entered the trade, strengthening a tradition that had been carried across generations.

The economic contributions of Purvis and her peers extended beyond their individual livelihoods. Their earnings, while modest, were often reinvested into their families and communities.

Records from the time show that successful Black vendors were able to purchase land, build homes, and even support the creation of schools, churches, and other community institutions.

In an era where financial stability was nearly impossible for most African Americans, the seafood trade became a lifeline—a means of achieving a measure of independence in an otherwise oppressive society.

Yet, the legacy of Mary Purvis is not merely one of economic resilience. She was a cultural icon, an embodiment of the strength, ingenuity, and perseverance of Charleston’s Black women.

The image of the oyster woman, balancing a basket atop her head and calling out in the Gullah dialect about “sweet oysters” and “fresh swimps,” became an indelible part of Charleston’s heritage.

Her voice, and those of her fellow vendors, became the rhythmic heartbeat of the city’s street life, a constant reminder of the deep African American roots in the region’s food culture.

Today, historians and heritage communities recognize Purvis as a trailblazer of Black entrepreneurship. She stands as an example of how, even in the face of systemic barriers, Black American women found ways to build economic agency.

Though details of her later life remain scarce, her presence in Charleston’s history is undeniable. In the story of the city’s food culture, Mary Purvis was not just a vendor; she was an institution. She transformed a humble trade into a thriving business, providing a model of self-reliance and enterprise that would inspire generations to come.

Her story serves as a testament to the power of Black women’s labor and ingenuity—an enduring reminder that, even in the most restrictive of times, entrepreneurship could be an act of liberation.

Through the simple act of selling oysters, Mary Purvis carved out a legacy that still resonates today, proving that economic independence, cultural preservation, and resilience are forever intertwined.

For just $6 a month or $60 a year, you unlock exclusive access to a close-knit community eager to explore groundbreaking authors and books.

Join us today as a paid member supporter. Or feel free to tip me some coffeehouse love here if you feel so inclined.

Your contributions are appreciated!

Diamond Michael Scott, Global Book Ambassador

I have great faith in the ingenuity of individuals, and I think the world would be a better place if we could find ways to get out of their way.

She, unfortunately, is not that well known in today's Charleston, at least among the Charleston Tour Guides (who are licensed by the city). There are several Gullah Tours and they may talk about her and her fellow street vendors (I'm embarrassed to admit that I haven't taken a Gullah Tour yet).

They were a vibrant part of early Charleston, and were still around in the 1930s (I think that WWII ended that era.