School Desegregation and Intolerance in Clinton, Tennessee

Book Review By Guest Contributing Writer Marc S. Friedman

By Guest Contributing Writer Marc S. Friedman

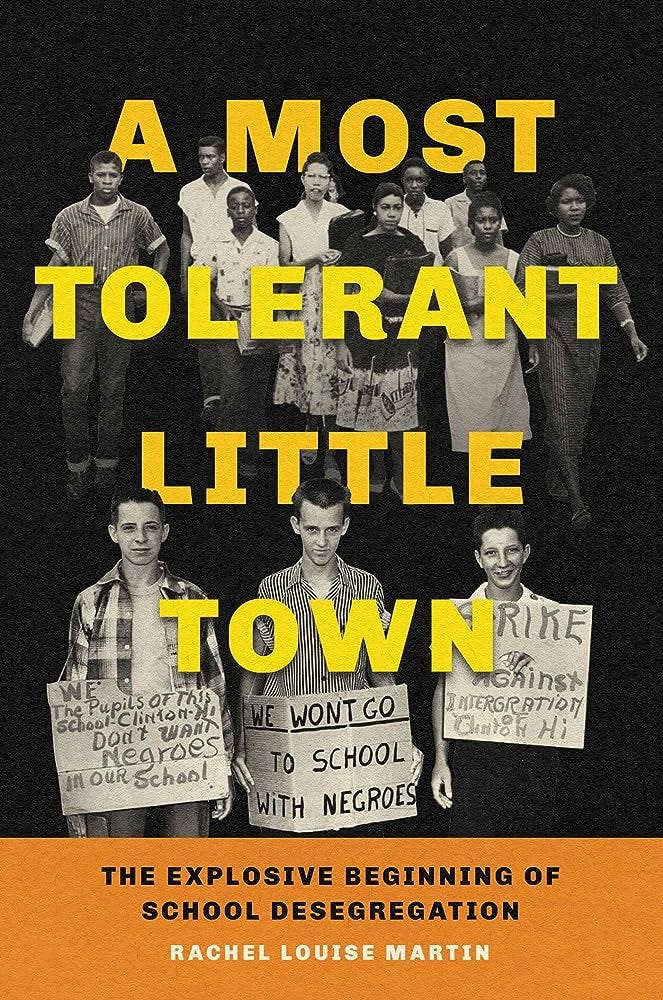

In the book “A Most Tolerant Little Town,” author Rachel Louise Martin takes readers on a powerful journey through the forced desegregation of Clinton High School in Clinton, Tennessee. This pivotal period in U.S. history emerged on the heels of the United States Supreme Court’s 1954 landmark decision in Brown v. Board of Education along with a subsequent ruling by Federal District Judge Robert Taylor in Knoxville that compelled the City of Clinton to desegregate its high school.

At first glance the book’s title is a bit sarcastic as Clinton was anything but “tolerant” when it came to White students going to high school with Black students. Because of the efforts of White citizens groups, led by Clinton’s luminaries, the Ku Klux Klan, as well as racist White high school students, Clinton could be more aptly described as “A Most Intolerant Little Town.”

By the 1950’s, most of Clinton’s Black residents lived in a section of town called “Freedmen’s Hill” where many emancipated Black families had laid down roots during post-Civil War Reconstruction. Although all-White Clinton High School, considered an excellent school at the time, was located only three-eighths of a mile down the hill from Freedmen’s Hill, Black students, like many throughout the South, were forced to attend segregated and inferior Black-only high schools many miles away.

In 1954, a unanimous United States Supreme Court known as Brown v. Board of Education (Brown I), ruled that racial segregation of children in public schools was unconstitutional noting that segregated schools are “inherently unequal.” In 1955, the Supreme Court issued a second opinion in the case (Brown II), unanimously ruling that localities must act to desegregate and move to full compliance with the principles in Brown I “with deliberate speed.”

In August 1956, the first school year after Brown II, twelve Black high school students from the Hill tried to enroll in Clinton High School. Their efforts were met with strong opposition by White segregationists, including the town’s Board of Education, who used intimidation, threats and violence to prevent the students from attending Clinton High School.

A lawsuit was filed in the Knoxville Federal Court for an injunction to stop the segregationists from interfering with the Black students attending the high school. Recognizing that the Supreme Court in Brown II required schools to desegregate with “all deliberate speed,” District Judge Taylor issued an injunction and, later, more orders intended to allow high school desegregation to proceed without White interference.

But the racist White community would not stand for it. After two weeks of relative calm following the school’s opening in August 1956, they began a merciless campaign of terror, assaults, beatings and bombings to prevent the desegregation of Clinton High School. As justification for these brutal acts, many, in fact, asserted that God was on their side and that the separation of races was His will.

Their campaign to prevent the desegregation of Clinton High School continued with haste and never fully subsided as Judge Taylor’s injunction and orders were violated across Clinton on an almost daily basis. Even multiple arrests did not stop the racist White citizens from engaging in brutal terror, assaults, beatings and bombings.

Within two years, the high school was destroyed in the early morning hours by three large kegs of dynamite carefully placed to turn Clinton High School into a pile of rubble. No one was ever arrested. Many White citizens seemed to know who was responsible but they would not say.

Over several years author Rachel Louise Martin engaged in meticulous research, creating a narrative that enables the reader to visualize the dreadful events that occurred in Clinton. She interviewed a large number of eyewitnesses to the events noting that this wasn’t always easy as the respondents were not always forthcoming. By way of example, one founder of the Tennessee White Youth, a student organization (largely young White girls) formed to oppose desegregation, said, “Honey, there was a lot of ugliness down at the school that year, best we just move on and forget it.”

But the Black students and their families were not able to “move on and forget it.” Their scars ran deep and lasted a lifetime. In 2007, a poignant monument was erected on Freedmen’s Hill to memorialize the events of 1956 and beyond. Statues of the 12 courageous Black students were erected on the Hill. Their bravery and resilience inspired others throughout the South who bravely fought against segregation. However, even in adulthood many of them, including those whose families took them away to California and elsewhere before graduation to avoid danger, exhibited signs of PTSD.

There were many acts of heroism in Clinton. Besides the students themselves, their families demonstrated great resolve and bravery. For example, the fathers of families on Freedmen’s Hill would arm themselves and stand guard at night to protect their families, including when the robed and hooded KKK conducted their infamous “night rides.”

Throughout the book the author skillfully immerses the reader in the events that occurred in the “most tolerant little town” following Brown I and II. In telling the story of the brutal encounters, Ms. Martin effectively conveys the hopelessness along with the courage of the affected students and their families. The story of the “most tolerant little town” comes alive through the many witness interviews she conducted, providing an important oral history of these events.

The book highlighted a number of White heroes, including those who courageously set aside their own racial views to do what was right by following the law. First, there was Judge Taylor who, despite enormous community pressure, would not countenance disobedience of the law and, especially, the Supreme Court’s rulings. Then there was D.J.Brittain, the White principal of Clinton High School. Given the racist White community’s uncontrollable rage, Principal Brittain had the impossible task of implementing Brown I and II while keeping the Black students safe and secure.

He didn’t always succeed, unfortunately. Brittain was relentless in his efforts until the steady stream of serious threats against he and his family forced him to resign and move to New Jersey. Many years later, Brittain returned to Clinton and, after a few years, committed suicide by shooting himself. As the author wrote, “[t]he only thing he asked of his family was that they destroy all of his papers and records relating to desegregating Clinton High School.”

Also there was Mayor W.E. Lewallen and his brother, William Buford Lewallen, the City Attorney. Despite immense community pressure, the Lewallen brothers understood that, as Americans, they needed to put their own feelings about race aside and obey the U.S Constitution and orders of the Federal Courts.

This obedience to the Constitution and laws despite one’s personal or political feelings is sorely needed today as too often we see politicians and others place their careers or party politics ahead of the Constitution and laws.

Perhaps the most notable among White citizens who fought for desegregation of Clinton High School was Pastor Paul Turner. Despite the anger and protestations of many of his dwindling Baptist congregants, Pastor Turner believed he needed “to lead our church to do the right thing.” As a result of his advocacy, he was severely beaten within an inch of his life by members of the local White Citizens’ Council. Yet, the next week he preached, “there is no color line at the cross of Jesus.”

Like Principal Brittain, Pastor Turner was forced to move away from Clinton. He relocated to San Francisco to teach at a seminary. In 1980, in an act reminiscent of the aforementioned Principal D.J. Brittain, he picked up his handgun and shot and killed himself. His family and friends believed the suicide resulted from his depression over what had happened 25 years earlier in Clinton. Sadly neither Principal Brittain nor Pastor Turner was able to “move on and forget it.”

The desegregation of Clinton High School, of course, was the object of intense national interest. All major networks and newspapers were reporting on Clinton High School and the White citizens’ resistance to desegregation. In fact, the famed columnist and radio commentator Drew Pearson made it his personal cause. However, the press frequently, and falsely, created the image that the troublemakers in Clinton were uneducated, blue collar men and women.

This myth served those (as it still does) who believe that these individuals did not share in society’s racism. Blame for Clinton’s troubles they assert should be cast on this small working class of individuals The truth here is that most of those involved were comfortably middle-class and above. They included business owners, entrepreneurs, police officials, lawyers, doctors, government officials and clergy, many being card-carrying members of the White Citizens Council and/or the KKK. Some were graduates of Ivy League schools and other prestigious institutions. Many were among Tennessee’s elite.

Clinton is not just a slice of Black history. It is an important chapter in American history that should be taught in our schools. As the philosopher George Santayana famously said, “Those who cannot remember the past are doomed to repeat it.” Every effort should be made to ensure that the saga of “The Most Tolerant Little Town” is not repeated.

As in my case, you may never have heard of Clinton, Tennessee. In Civil Rights history this “most tolerant little town” is no more than a footnote, being overshadowed by Little Rock, Birmingham and other better-known Civil Rights battlegrounds where, like tiny Clinton, White Supremacists deeply resisted integration of its schools. While the author has performed a great service by telling Clinton’s story, I readily admit that reading about it was quite painful.

Let us never forget the tragedy of Clinton. Heeding the advice given to the author by the Founder of the Tennessee White Youth to “just move on and forget it” makes no sense given the searing impression the book leaves of the cruelty directed at the 12 Black high school students and their families. Most importantly, it gives the reader a profound and lasting appreciation of the unsung heroism of the resolute Black citizens of Clinton and their White allies who resisted.

This is a great article. As a TN native who entered the “newly” integrated school system as 1 of 3 black students until the 3rd grade, I can relate to much of it in a very personal way. These stories must be told and remembered especially in light of the current assault on public education. Nothing new under the sun. TY🫶🏽

When will the Catholic fanatics reverse 'Brown'?