Taking a Swing at Jim Crow

The Legendary Boxing Achievements of Jack Johnson …..in Black and White

Born in Galveston, Texas, John Arthur (Jack) Johnson (1878 - 1946), was an American boxer who, during the Jim Crow era, became the first Black heavyweight boxing champion of the world. While success in the ring made him a folkloric celebrity worldwide, few today sadly have even heard of him.

A highly controversial figure, who was both admired and feared, Johnson’s boxing prowess and ascension occurred during a period in history when championship bouts among boxers were restricted to white men.

Determined to make his mark on the world stage, Johnson followed World Heavyweight Champion, Tommy Burns, across the globe for two years, relentlessly taunting Burns whenever he turned down a fight. Johnson even purchased ringside tickets to Burns’ matches in order to hurl insults toward him while he fought.

In 1908, Burns finally caved in and agreed to fight Johnson, an announcement that garnered worldwide attention. Because it was recorded with high-quality film, a rare occurrence at that time, millions of people globally were able to take in the epic fight.

With thousands of spectators in attendance in Sydney, Australia, Johnson defeated Burns in 14 rounds to claim his first world boxing championship. He would hold onto the crown for seven more years, a remarkable feat, given the racial hatred, bigotry, and segregation that were rampant throughout the United States at the time.

Known for his adroit footwork and powerful presence in the ring, the man known as the “Galveston Giant” achieved massive success in the ring. Many historians consider this an epic achievement considering that the end of slavery had occurred a mere 13 years prior in Galveston, his birthplace.

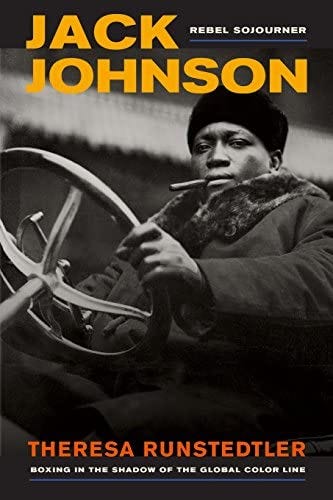

Historian and writer Theresa Runstedtler, author of the book Jack Johnson, Rebel Sojourner: Boxing in the Shadow of the Global Color Line (University of California Press, 2012) notes that boxing fans at the turn of the century viewed sports from a race and nationality narrative. This led to their rabid interest in boxing matches that pitted Black boxers against White boxers in what Runstedtler has referred to as sort of a “Darwinian struggle.”

These battles she says became kind of a metaphor for race relations noting that “if a white man won, it would reinforce ideas of white supremacy. But if a Black man won, then it would upend ideas of white supremacy.”

According to Runstedtler, Burns' stunning defeat to Johnson disrupted the prevailing white supremacy narrative, adding “Johnson holding on to the heavyweight crown was just not acceptable in an era of white imperialism, Jim Crow, and global white supremacy.”

From the moment of Johnson’s stunning achievement in winning the crown, white Americans began a relentless quest to identify the next "Great White Hope" to challenge and defeat Johnson. Two years later, they believed they had found their guy in former undefeated heavyweight champion James J. Jeffries.

In a highly celebrated 1910 boxing match in Reno, Nevada, he beat Jeffries, a man who had retired from boxing as a champion five years prior, by knocking him out in the fifteenth round. His victory fueled racial violence throughout the U.S., killing nearly 20 people and injuring hundreds — the vast majority of them Black.

As the 20th century continued to take shape, growing attention around the film capturing the Jeffries fight turned Johnson into a powerful symbol of Black resistance. Over time it became a lens through which everyday people, boxing sports enthusiasts, and promoters discussed racism and the Black experience in America.

Johnson's success in the ring garnered him a great deal of international interest, often celebrated with ceremonies and parades in some Black communities. Outspoken, free-thinking, and a bit cocky with his wealth, Johnson had no qualms in stirring the ire of racists as well as some Black intellectuals.

But even more discomforting to the media and court of public opinion was his brash tendency to challenge society’s disapproval of interracial dating, which was illegal in many U.S. states. Three of his marriages were to white women, the brazenness of which culminated in his arrest on a couple of occasions for violating the Mann Act ("transporting, in interstate or foreign commerce," a woman for "immoral purpose.") In 1913, he was found guilty by an all-white jury, even though the issue was fueled by the woman he was married to at the time.

In a bold move precipitated by this decision, Johnson fled into exile. Using the great wealth he had amassed as a boxer, he lived lavishly and boxed everywhere he traveled. While residing in Spain and Cuba, he fell deeply in love with Spanish culture.

After several years on the run, Johnson in 1919 decided to settle down in Mexico during the tail end of the Mexican Revolution. Inspired by the revolutionary atmosphere, he became a boxing instructor for a number of prominent Mexican authorities, including a cadre of high-ranking generals.

Over the course of his exile and travels around the world, Johnson crossed paths with many influential people, allowing him to capture unique insights about racism, imperialism, and global politics.

After his verdict and conviction, Johnson fled to Europe. He eventually returned to the United States in 1920 to serve a one-year prison sentence. Upon release, he headed straight to Harlem, where crowds of fans hoisted and carried him through the streets in celebration. This occurred on the heels of the Black American artistic movement known as the Harlem Renaissance.

In the book "Jack Johnson the Man," published in 1933, which includes writing by and about Johnson, he offers readers an inside look at his boxing technique and his dietary regimen. It was also a platform for Johnson to speak out against the racist treatment and public ridicule he experienced.

In his book, he described his life like this:

"My life, almost from its very start, has been filled with tragedy and romance, failure and success, poverty and wealth, misery and happiness. All these conflicting conditions that have crowded in upon me and plunged me into struggles with warring forces have made me somewhat of a unique character in the world of today and the story of my life I have led, may therefore not only contain some interest if told for its own sake, but may also shed some light on the life of our times."

Johnson died in a car accident in 1946. The June 15 obituary in the black-owned New York Amsterdam News was "They Hated Jack Johnson For He Feared No Human."