The “Black Banking” Empire of Jesse Binga

Jesse Binga (April 10, 1865 – June 13, 1950) was a prominent businessman, real estate titan, and civic leader, who founded the first privately owned Black bank in Chicago. His legacy as an enterprising pioneer in the U.S. financial sector paved the way for community banks in other Black communities throughout the nation.

Born in Detroit on April 10, 1865, a mere four days before President Lincoln was assassinated, Binga was raised in a family of ten children. His father, William W. Binga, who was a barber, along with his mother, Adelphia Lewis Binga, a Detroit and Rochester (NY) real estate entrepreneur and housing developer, played a pivotal role in Jesse’s aspirational development.

As a youth, Jesse Binga dropped out of high school to begin assisting his mother in collecting money from renters. He later moved to the Seattle/Tacoma, Washington area and then Oakland, California to follow in his father’s footsteps as a barber. Later Binga joined the infamous Pullman Porter, saving money to acquire real estate in Pocatello, Idaho which he sold for a nice profit.

In 1893, Binga made the move to Chicago after attending that year’s World Fair. Mirroring his mother’s path, he began pursuing real estate ventures by acquiring and repairing dilapidated buildings with the goal of renting them out.

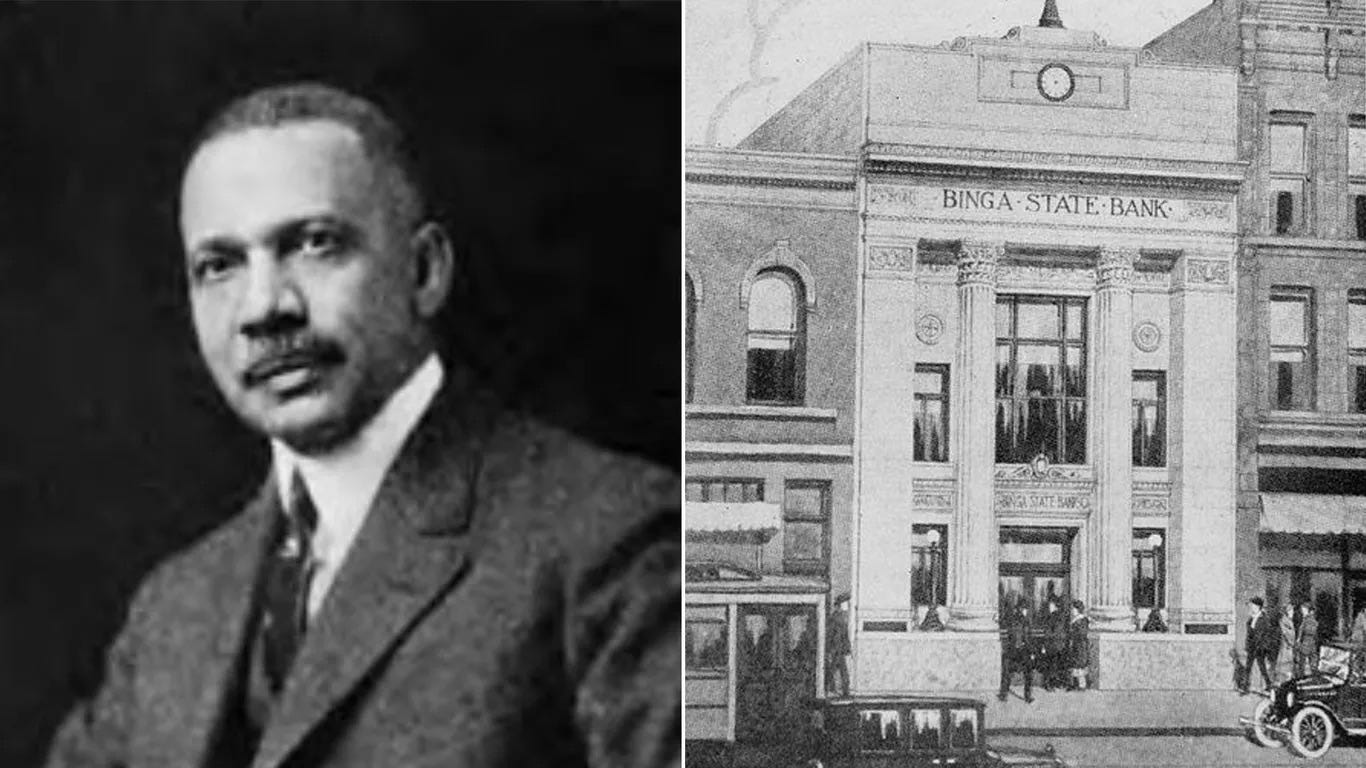

His next major opportunity came in 1907 when Chicago’s white-owned McCarthy Bank failed. Binga swooped in to purchase the building, chartering his own bank as a private credit institution. He named it Binga Bank, opening it in 1908.

With his business trajectory now in full bloom, Binga married Eudora Johnson in 1912. She came from one of Chicago’s wealthiest and most prominent black families. Her brother was gambling king John “Mushmouth” Johnson, owner of a well-known local saloon who died in 1907. Eudora reportedly inherited over $200,000 in 1912 from him (worth an estimated $5,913,787.23 today) after the final accounting of his passing.

The lavish wedding was arguably the most watched in the city that year and reflected Binga’s growing stature as a respected business leader nationwide. Prominent black race reformer Booker T. Washington, in fact, reportedly sent a note of congratulations to the newlyweds.

In time Eudora’s family money and Binga Bank’s capital were merged, providing the enterprise with the requisite assets and market strength to become the biggest bank in Chicago’s Black Belt. On the heels of Chicago’s population explosion in the first two decades of the 20th century, Binga State Bank was in full swing. A few short years later the bank had deposits of $1.3 million (worth an estimated $37,250,762.89 today).

Bank assets aside, Binga was also the owner of several South Side Chicago properties. This was during a period when Black transplants were migrating to area communities in groves, expanding, in fact, into historically white neighborhoods. As white residents fled these areas, Binga established a presence as the “de facto broker” between white sellers and black purchasers.

It was during this period that Binga saw a meteoric rise in prominence, a status he continued to hold for many years. This ascension however drew the ire of many white locals who resented his tireless work in helping to settle black residents in neighborhoods that had previously been exclusively segregated.

With the 1919 Chicago Race Riots having fueled violence and destruction, his South Side residence was bombed seven times over a two-year period. Whenever his house was damaged, those salty about his presence and positive achievements in the neighborhood would offer to purchase his home. He refused, electing to rebuild and remain with 24-hour security which he paid for. At one point Binga even offered a $1,000 reward for the conviction of the bad actors who were bombing his place, but they were never arrested.

While his businesses were also targeted with malicious acts, the biggest threat to his growing empire was the emergence of other Black bankers seeking a piece of the action. Through the crafty use of state regulation to run interference against these competitive winds, Binga found a way to successfully eliminate private banks through edicts requiring them to possess state or federal charters along with at least $100,000 in capital. In the end, Binga Bank, renamed Binga State Bank, was the only Black Belt bank able to reach that threshold.

In 1924, Binga acquired a new swath of property located at the northwest corner of 35th and State Street in Chicago, making this the spot of his newly chartered $120.000 bank building. Adorned with marble and stone, the rich architectural esthetics offered a striking presence, attracting the attention of pedestrians in the area. Moreover, the interior inner sanctum featured walnut paneling replete with a magnificently eye-catching steel vault.

Binga’s bank team featured a collective of highly educated and bright professionals from prominent academic institutions like the University of Chicago, the University of Michigan, and Oberlin College. Binga himself sat behind a massive glass window and marble desk that offered a panopticonic view of the workspace.

To accommodate his rising fortunes, Binga 1927 purchased a swath of additional property adjacent to that location for an even larger structure. A couple of years later he built the grand Binga Arcade, a building that featured offices, shops, and a dance floor, at 35th and State Street in Chicago.

With his growing repute among Black Chicagoans, Binga emerged as a leading symbol of capitalism and economic hope. He served as a writer on business and real estate for the prominent Black newspaper Chicago Defender. He also published a book “Certain Sayings of Jesse Binga,” filled with his business and life wisdom.

Binga was also involved with Chicago-area civic activities, establishing a business forum known as the Associated Business Club where aspiring Black entrepreneurs could gain access to lectures from high-profile Chicago-area business leaders from all races. His ongoing philanthropic interests included the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA) as well as a number of historically black colleges including Fisk, Howard, and Atlanta University.

In 1929, at the peak of his meteoric ascension, Binga, now in his 60s, began exploring funding opportunities in the hopes of launching a second bank replete with a federal charter. Unfortunately the following year Binga saw a precipitous fall in his banking fortunes, the effects of the Great Depression. By that summer, the bank’s cash reserves had dwindled, putting a halt on leading activities. This led Binga to dip into his own pocket in order to keep his activities afloat, a move that proved unsuccessful.

On July 31, 1930 state bank auditors in a move shocking to many, shuttered Binga State Bank, pointing to insolvency and accounting irregularities. As word of this emanated throughout the city, crowds of worried depositors began swarming the main bank location which was under police protection.

Few, however, knew about the brewing criminal case against Binga, which surfaced when the audit revealed some missing funds. Authorities agreed to allow the bank’s board time to raise the needed funds. The board agreed to this under the condition that Binga step down from his post which he refused to do.

In a final push to save the bank, the Chicago Clearing House, of which Binga State Bank was a member, met to decide whether to back the bank with funding to ensure its reopening. The members, however, were hesitant to take on this risk, largely due to the Binga embezzlement rumors.

By the fall of 1930, Binga State Bank, with depositor funds having been completely depleted, was unable to continue operating. Binga’s nightmare continued as he was forced to declare bankruptcy. Even his wife, Eudora, turned on him, pursuing legal action against her husband for neglect of family affairs. She requested that the court appoint a conservator to oversee what little money remained.

The following year, Binga was firmly charged with embezzlement tied to $39,000 in pledges that were earmarked for the proposed national bank that never opened. The trial led to a hung jury leading to a mistrial.

In 1933 a second trial led by the state’s attorney resulted in Binga being sentenced to ten years in state prison. He remained free awaiting an Illinois Supreme Court appeal which was later denied. As a result, Binga in April of 1935, at the advanced age of 70, entered prison in Joliet, Illinois.

A year later prominent attorney Clarence Darrow, appeared on Binga’s behalf noting in court:

"I have known Binga for thirty years and he is a man of fine character. He lost a fortune trying to keep his bank open."

While this appeal was denied, a parole hearing that took place a couple of years later was successful. At this hearing, scores of signatures were presented in support of Binga’s release. Among the signatories were depositors who lost money due to the bank’s failure.

After his release, Binga returned to his South Side Chicago home. Now paroled, financially ruined, and in declining health, Binga fought to keep creditors at bay who were seeking to take his home by working at a local school as a janitor. Binga passed away in 1950 without sufficient funds to even place his name on the family’s Oak Woods Cemetery headstone.

Former Chicago Sun-Times Editor-in-Chief Don Hayner author of the book entitled “Binga: The Rise and Fall of Chicago’s First Black Banker” says that he first learned of Jesse Binga in 1987 while a reporter doing a 150th-anniversary story for the Sun-Times marking Chicago’s 1837 incorporation as a city.

“I was assigned to find the oldest white family in Chicago and the oldest Black family and tell their stories about their generations in Chicago. It was through this research that I learned of George Mead, who came to Chicago as a teenager in 1849.”

This, says Hayner, is what led him to Binga, who was related to the Mead family through marriage.

“I was inspired first by Binga’s entrepreneurial drive, but mostly by his fearless individualism. He didn’t back down even as his home and businesses were bombed eight times when he moved into a white neighborhood and as he helped black families move out of Chicago’s overcrowded Black Belt.”

Since Binga died almost forty years before Hayner began his research, Hayner says that his first order of business would be to find those who may have known him or had personal contact with Binga. Given the timing, he says, there were few. Yet he found about a dozen friends, business associates, and relatives including one whose mother and father both worked for Binga.

Those interviews, according to Hayner, were the foundation of what came next, his deep dive into court documents, census tract records, academic papers, newspaper clips, and correspondence notes between Binga and others who knew him. Adds Hayner:

“What was shocking to me was that his story had never really been told. So my natural curiosity then went from there.”

Continues Hayner:

“He was a self-made man. He was self-educated too but he was smart naturally. I mean he was great with numbers from what I understood and could tabulate quickly and was often mentioned for that. He was a great negotiator, a hard negotiator.”

Hayner says that the biggest surprise from his exhaustive research was his discovery that Binga had a beneficial relationship with some of our nation’s most powerful white businessmen and politicians.

“It was practical and served both parties. This is despite his detractors who said that Binga was a self-made man who just wanted to make money and gain power. While the fact that he worked for wealth and power was in part true, Binga always felt a responsibility to his community.”

In the end, those relationships assert Hayner, not only helped Binga in his rise to wealth but also helped the Black Belt. He says that it’s remarkable that all this was done during a period of open discrimination and hostility toward the Black community, particularly those acts targeting Binga.

Asked about how Chicago Black Belt informed Binga’s aspirations, Hayner shared this:

“Chicago’s Black Belt was originally a two-mile narrow strip of Chicago’s South Side created by discriminatory practices, laws, and customs. Despite and to some degree because of this segregation Black entrepreneurs thrived in the Black Belt. There were Black-owned cab companies, bakeries, clothing stores, and funeral homes. Tailor shops and many other enterprises. And, of course, there was entertainment: gambling, dancing, and incredible music—jazz, blues, Dixieland, and rhythm and blues flourished in the Black Belt.”

Hayner says that as the Great Migration of Blacks from the South began, the Black Belt became increasingly overcrowded, which meant that people were forced to live in properties built for much smaller populations. Because something had to give, Binga adds that Hayner started to expand the area where Blacks could live. That, he says, meant that Binga could also expand his real estate business and his banking empire as he offered mortgages to Blacks to purchase homes along with apartments to rent.

“Sadly these actions, however, Binga became a target for some in the white community and in 1919 he became a lightning rod for the worst race riots in Chicago history.”

Hayner offered this thought about Binga’s legacy:

“He showed that despite vicious discrimination and opposition, Black Americans could build wealth through discipline and tenacity.” Many people thought if Binga can do it, maybe we can too. He was a beacon of hope for people to achieve first the foundation of the American Dream—owning a house. Binga helped create an enduring narrative of Black success and achievement in one of the most segregated cities in America.”

He concludes:

“In a way, I think this book is a message to the white community about entrepreneurs and Black entrepreneurs and the obstacles that at times they run into that white entrepreneurs don’t. And I think that’s a good message.”