The Chicago Defender: Now For The Rest of the Story

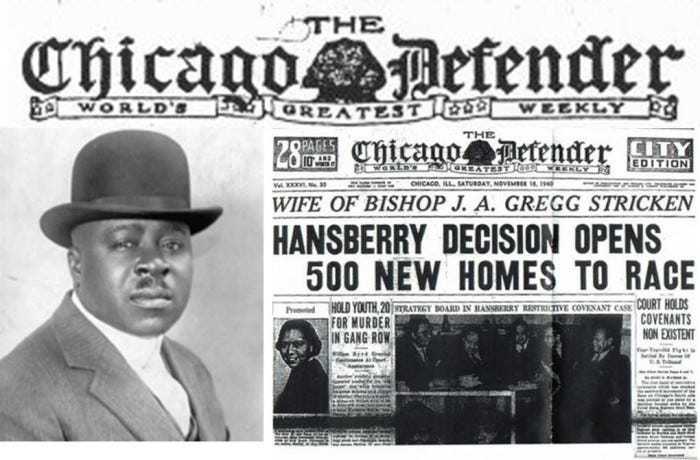

Launched in 1905, the Chicago Defender was the very essence of a small business startup. Bootstrapped with founder Robert Abbott’s last 25 cents, it eventually emerged as one of the most influential newspapers in U.S. history. The publication quickly saw a meteoric rise, amassing millions of dollars while helping bring attention to the history of Black America during the 20th century.

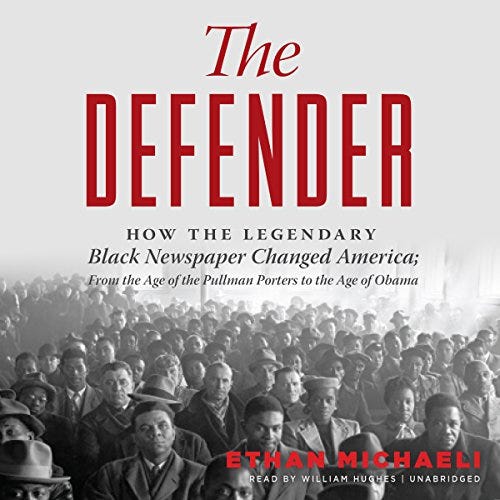

Ethan Michaeli in his bestselling book “The Defender: How the Legendary Black Newspaper Changed America,” chronicles the epic rise, impact and significance of this iconic Black newspaper. A copy editor and investigative reporter at the Defender from 1991 to 1996, Michaeli offers a documentary style narrative of the paper’s relentless fight for Black justice and equality.

The book begins with the profoundly moving story of Abbott who we recently featured in a separate feature piece for “Black Books, Black Minds.” A thought-provoking book, I highly recommend it to anyone seeking a broader context of America in the 20th century, newspapers during that time frame, and the Black press in particular.

We recently reached out to Michaeli to learn more about his journey in writing the book and the legacy he hopes to leave. Here is what he had to share:

What led to your interest in the history of The Defender?

EM: I worked at The Defender from 1991-1996, first as a copy editor and then as an investigative reporter covering crime, public housing, and environmental issues. When I started, I didn’t know anything about The Defender’s long history as an African American institution. I wasn’t from Chicago originally and got the job on the recommendation of a friend who was also white and Jewish not long after I graduated from the University of Chicago.

Can you describe what that experience was like?

EM: I was very lucky to be there for the last few years of John Sengstacke’s long reign over the newspaper. He had taken over in 1940 after the death of his uncle, founder Robert S. Abbott, having been mentored by many legendary editors and renowned reporters. For me, it was an education in a corrected version of American political history, one that fully included African Americans, and placed the struggle for civil rights at the center of the national historical drama.

How long was your stint there?

EM: I left The Defender after 5 ½ years to start a magazine written for and by tenants in the city’s public housing developments as well as an affiliated not-for-profit organization, a job I held for nearly two decades. I always wanted to do a book about The Defender, though, and when Barack Obama was elected to the presidency in 2008, I was able to convince a publisher that his election was the culmination of more than a century of careful planning by the African American-led political movement in which the newspaper was a central player. Other former Defender staffers, Black and white, had written books about their experiences, but I felt that this was the moment to do a comprehensive history of the newspaper and its accomplishments.

While researching the book, what was your biggest surprise discovery?

EM: In the course of researching it, I realized that the struggle for civil rights had started much earlier than I thought. Robert Abbott’s first trip to Chicago was for the 1893 World’s Fair, where he met the great Frederick Douglass, then 75 years old and the preeminent spokesperson of African Americans. Douglass gathered around himself a whole generation of young African Americans at the Fair, including Ida B. Wells and James Weldon Johnson, and inculcated in them a mission of fighting for civil rights in the 20th century as a continuation of the 19th century’s struggle for emancipation.

The story of Abbott is surely an interesting one. Can you expand upon this a bit?

EM: Still a college student during the Fair, Abbott heard Douglass clearly, especially when the great man emphasized that newspapers were an essential tool for organization as well as to counter racist propaganda. Abbott came back to Chicago several years after he graduated from college and launched The Defender in 1905 with that same sense of mission, which he transmitted to the reporters, distributors and even the children who delivered the newspaper. Protected by a substantial, prosperous African American community in Chicago as well as the relatively liberal laws of Illinois, The Defender published blistering accounts of the atrocities which were commonplace in the South, where more than 90 percent of African Americans lived in those days under legalized segregation and the near-constant threat of violence.

The white supremacists who ruled the South were pernicious, highly organized and utterly ruthless, broadcasting racist imagery and themes through daily newspapers, theatrical productions, and, eventually, through major motion pictures like “Birth of a Nation.” In its earliest days, therefore, The Defender saw itself as ‘defending’ African Americans from its base in Chicago, where the newspaper could publish freely and send newspapers to the South.

How has interest in the book held up since it was first released?

EM: Since the publication of “THE DEFENDER” nearly seven years ago, I have been invited to give lectures at universities and private institutions around the world, and have been positively inspired by the people I have met. Among the highlights, in 2017, I spoke at the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center in Cincinnati, Ohio, and the following year, I participated in an academic conference in Paris, France, that brought together scholars, writers, and artists from around the world. It has been especially moving to speak at high schools and elementary schools and to show young people the historic photographs of Robert Abbott standing in front of his printing press or meeting with dignitaries; they are amazed at what he accomplished ‘so long ago.’

Of all the places I’ve been lucky enough to visit, though, the one that stands out in my memory is St. Simon’s Island in Georgia, where Robert Abbott was born. Meeting some of Mr. Abbott’s family there was deeply meaningful to me. On a more practical side, the rights to make a television series based on “THE DEFENDER” have been bought, and I’m really excited by the way that’s coming together.

Please share a little about the significance of The Defender in terms of the history of Chicago as well as on a broader scale with the Great Migration.

EM: The Defender catalyzed the Great Migration, using its editorial page to encourage African Americans to come to Chicago and other northern cities as an act of economic and political liberation that would benefit the people while it undermined the oligarchs of the South. At first, Robert Abbott did not support a large-scale migration to the North as he knew personally how difficult it was for African Americans to find jobs. Not only did employers themselves discriminate, but labor unions blocked the hiring of African Americans as well. But when World War I started, the supply of immigrant workers from Europe suddenly stopped just as demand for American products surged. The only available workers in the country were largely African Americans in the South, which forced the large factories, packing houses and other industries as well as the unions to drop their refusal to hire African Americans.

So how did Abbott’s views evolve over the years?

EM: Abbott was still equivocal about the migration regardless, but when he saw that the departure of Black workers caused a labor shortage in several skilled fields, that, in turn, prompted political changes, he shifted gears. The Defender then began to extol the virtues of migration for the individual as well as the masses. While the front pages reported accurately on the difficulties of life in the North, the newspaper’s editorials averred that the benefits outweighed the obstacles, and soon the first waves of what it labeled “The Exodus” arrived.

As African-Americans from the South began arriving in Chicago, what did they experience?

EM: As African Americans got off the trains in Chicago, they were enlisted in political organizations that elected candidates on the local, state and ultimately the national level. The Great Migration, therefore, changed the nation’s demographics by bringing a sizable percentage of the African American population from the South to the cities of the North, and also shifted the nation’s political geography.

What is your greatest hope in terms of the legacy of your book “The Defender?”

EM: The Defender itself is still around today as an on-line news source. So first of all, I do hope that the book continues to shine the spotlight on the modern Black Press, drawing attention to African American media outlets as well as African American journalists and journalism about African American communities. We have a long way to go before we reach equity in any of those areas. Throughout its long history, The Defender has advocated for an integrated America, and for objective journalism in the American tradition, and I think those two ideals are also in need of defense these days.

I wasn’t the first white guy to work at The Defender; really, I wasn’t even the 101st. The newspaper had white employees from its earliest years and even one or two white editors, but always under Black owners and with the mission of serving its Black readers foremost. Likewise, the newspaper’s owners truly believed that there was great value in recording the quotidian events of African American people, their triumphs, tragedies and daily travails.

Where is your writing journey headed next?

EM: The experience of working at the newspaper is what shaped me as a writer, and my second book, “TWELVE TRIBES: PROMISE AND PERIL IN THE NEW ISRAEL,” covers a very different topic – modern Israel/Palestine – but includes a lot about the connections between African Americans, Africa and the Holy Land. My next book will build on both of these to explore the complex political alliance between African Americans and Jews in the United States.

Black Books, Black Minds” is a key foundation of my Great Books, Great Minds” passion project. For me, it’s a labor of love fueled by the endless hours of work I put into researching and writing these feature articles. My aim is to ignite a new world of community, connection, and belongingness through the rich trove of Black History books, thought leaders, and authors I unearth.

So if you are enjoying this digital newsletter, find it valuable, and savor world-class book experience featuring non-fiction authors and book evangelists on Black History themes, then please consider becoming a paid member supporter. Large or small, every little bit counts.”