The NAACP’s Unrelenting Fight for Racial Justice

Founded on February 12, 1909, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is the oldest, largest and most celebrated civil rights organization in the U.S. With more than a half-million members and supporters throughout the United States and around the world, the NAACP has established a long legacy of activism around racial justice, equal opportunity and voting rights among Black Americans.

According to most historians, the catalyst behind the NAACP’s formation was the 1908 race riot in Springfield, the capital of Illinois and resting place of President Abraham Lincoln. Appalled by the violent acts of bigotry committed against Black Americans throughout the nation, particularly in the Jim Crow South, a group of white liberals including Mary White Ovington and Oswald Garrison Villard, both the descendants of abolitionists, along with William English Walling and Dr. Henry Moscowitz sprung into action, seeking to forge a new narrative of racial justice. Around 60 people, including W. E. B. Du Bois, Ida B. Wells-Barnett, Mary Church Terrell and other prominent Black Americans, signed the call before releasing it on the centennial of Lincoln’s birthday.

Following the tone established at Du Bois’ Niagara Movement in 1905, the NAACP set out to remove racial discriminatory barriers prevailing during that time. The broader aim was to secure the rights guaranteed in the 13th through 15th Amendments of the U.S. Constitution, promising to end slavery, ensure equal protection of the law, and achieve universal suffrage.

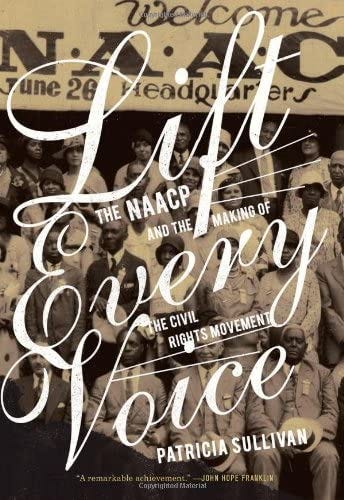

It’s here where the objective of ensuring the political, educational, social and economic equality of minority group citizens of the United States while eliminating race prejudice through the democratic processes is exquisitely capture in the book Lift Every Voice: The NAACP and the Making of the The Civil Rights Movement (2009) by noted University of South Carolina History Professor and Author Patricia Sullivan.

Throughout the pages of this book, Sullivan unearths a steady stream of thought leadership about the early decades of NAACP activism. She retells powerful stories of courage, bravery, and strategic maneuvering by formable figures like W.E.B. Du Bois, Mary White Ovington, Walter White, Charles Houston, Ella Baker, Thurgood Marshall, and Roy Wilkins. Buoyed by a set of legal victories culminating in Brown v. Board of Education, the NAACP built much needed momentum for its major push to dismantle Jim Crow once and for all.

As Sullivan notes in her book:

“The Niagara Movement gave structure and visibility to anti-Washington sentiments shared by a core group of leading place professionals and began the hard work of organizing widespread diddindence into a movement for racial justice. Its platform claimed for “African-Americans” “every single right that belongs to a freeborn American — political, civil, and social” and promised that “the voice of protest of ten million Americans” would “never cease to assail their fellows” until those rights were secured.”

The NAACP proceeded forward with establishing a national office in New York City, naming a board of directors as well as Moorfield Story, a white constitutional lawyer as its first president. The only Black American among the organization's leaders at that time was Du Bois. In the opening chapter of the book, Sullivan notes:

“On August 1, 1910, W.E.B. Du Bois arrived at 20 Vesey Street in downtown Manhattan, home of the New York Evening Post and headquarters of the newly established National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). After more than a decade at Atlanta University, the forty-two-year-old scholar left academic life behind to become director of publications and research for the fledgling organization. Years later, he recalled the sober greeting offered by Oswald Garrison Vuillard, NAACP treasurer and owner of the Evening Post. “I don’t know who is going to pay your salary,” Vuillard announced as Du Bois settled into his bare office.. “I have no money.”

Du Bois, who in 1910 ascended to the role of director of publications and research, established the Crisis Magazine, which served as the official journal of the NAACP in its Civil Rights crusade. It delivered key news pieces on the civil rights activity taking place while highlighting black art, writing, and poetry of Black Americans as a challenge to prevailing stereotypes. Over time it became the voice of the Harlem Renaissance, featuring works by Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen and other noted Black figures of that time. The publication’s prominence would rise over the years and still exists to this day.

By 1913, the NAACP had become a trailblazing influence in the civil rights movement, expanding its footprint to branch offices in cities like Boston, Massachusetts; Baltimore, Maryland; Kansas City, Missouri; Washington, D.C.; Detroit, Michigan; and St. Louis, Missouri. Featuring a rapidly growing legal team, the NAACP ignited a flurry of early court battles where they emerged victorious. This helped to elevate the organization’s importance as a respected advocate in legal cases involving racial injustice.

From 1917 to 1919, the NAACP’s membership grew at a rapid clip to over 300 local branches. James Weldon Johnson became the organizations first Black secretary in 1920 while Louis T. Write, a surgeon, became the first Black Board chairman in 1934.

Over time, the NAACP waged an unrelenting campaign against lynching and other acts of violence against Black Americans, particularly in the Jim Crow South. In a significant move, Johnson resigned as secretary in 1930 and was succeeded by Walter F. White. Fair-skinned to the point to where he could infiltrate groups by pretending to be a white person,White presided over the NAACP during arguably its more fervent period of legal advocacy.

Most notably in 1930, the association commissioned the Margold Report which emerged as a key document in the reversal of the separate-but-equal doctrine that had governed public facilities since Plessy v Ferguson in 1896.

In 1935, White brought Howard University law dean Charles H. Houston into the fold as the NAACP chief counsel. Houston’s work on school-segregation cases was a pathway for his protégé Thurgood Marshall’s success in Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, the decision that overturned Plessy v Ferguson.

Sullivan in “Lift Every Voice” chronicles how the Great Depression of the 1930s had a disastrous impact on Black Americans, leading the NAACP to refocus some of its efforts on the push for economic justice. She also shows how after years of terse encounters with white labor unions, the Association’s work with the newly created Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) buoyed efforts to ensure access to jobs for Black Americans.

The book explores how White, a friend and adviser to First Lady and NAACP national board member Eleanor Roosevelt, sought out her influence in trying to convince then President Franklin D. Roosevelt to eliminate discrimination in the armed forces, defense industries and the agencies spawned through the President’s New Deal legislation. Roosevelt ultimately relented, agreeing to free up thousands of jobs to Black workers when prominent labor leader A. Philip Randolph, in collaboration with the NAACP, threatened to proceed with a national March on Washington movement in 1941. In addition, Roosevelt agreed to establish a Fair Employment Practices Committee (FEPC) to ensure compliance.

During the 1940s, the NAACP witnessed a major growth spurt in its membership over a six-year stretch to nearly 600,000 members. During this period, it continued to advance its presence as a legislative and legal stalwart, advocating for federal anti-lynching laws and for an end to state mandated segregation.

By the 1950s, the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, headed by Marshall, achieved the major milestone of Brown v. Board of Education (1954), outlawing segregation in public schools. The NAACP’s Washington, D.C., bureau, led by lobbyist Clarence M. Mitchell Jr., was particularly noteworthy, helping to not only fuel the movement towards integrating the armed forces in 1948 but also passage of the Civil Rights Acts of 1957, 1964, and 1968, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Despite these gains, progress, however, was slow, harsh, and often met with a violent response and retribution. The unsolved 1951 murder of Florida NAACP field secretary Harry T. Moore and his wife, their home bombed on Christmas night was a sobering reminder of the inherent dangers tied to the racial justice movement. Moreover, violent pro-segregationist often targeted NAACP Mississippi Field Secretary Medgar Evers and his wife Myrlie. In 1962, their house was firebombed. He was later assassinated right in front of his home.

In lightning rod events, Black children attempting to enter previously segregated schools in Little Rock, Arkansas, were met with racial taunts and violent acts. And throughout the South, Black Americans faced grave dangers and risks attempting to exercise their rights to register and vote.

In the 1950s and 60s, the Civil Rights Movement ushered in a new period of activism led by leaders such as Martin Luther King Jr. While echoing the sentiment set by the NAACP, many in King’s circle at the Southern Christian Leadership Conference felt that more direct, on-the-ground activism was needed to achieve the broader aims of the movement.

Sullivan’s book “Lift Every Voice” offers a well-researched look at the early foundation of the NAACPs work and the movement it spawned to awaken the consciousness of our nation. Today, the organization remains a pivotal player in the racial justice movement, promoting the legacy of Black opportunity and freedom.

—

Black Books, Black Minds” is a key foundation of my Great Books, Great Minds” passion project. For me, it’s a labor of love fueled by the endless hours of work I put into researching and writing these feature articles. My aim is to ignite a new world of community, connection, and belongingness through the rich trove of Black History books, thought leaders, and authors we unearth.

So if you are enjoying this digital newsletter, find it valuable, and savor world-class book experience featuring non-fiction authors and book evangelists on Black History themes, then please consider becoming a paid member supporter at $6.00/month or $60.00/year. Large or small, every little bit counts.”