The NAACP’s Unrelenting Fight for Racial Justice and Independence

Founded on February 12, 1909, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is the largest and oldest civil rights organization in the United States. With more than two-million members and supporters throughout the world, the NAACP has a long track record of impact in areas like racial justice, equality, and voting rights for Black Americans.

NAACP’s formation was largely catalyzed by a 1908 race riot in Springfield, the Illinois state capital and resting place of President Abraham Lincoln. In response to the violent racism directed towards Black Americans, particularly in the Jim Crow South, a cohort of white liberals led by two descendants of abolitionists, Mary White Ovington and Oswald Garrison Villard fueled the NAACP’s founding with a mission centered on racial justice.

With this movement having been ignited, nearly sixty people including the likes of W. E. B. Du Bois, Ida B. Wells-Barnett, Mary Church Terrell and other prominent Black American signed the NAACP founding document. It was later released on the centennial of Lincoln’s birthday.

Inspired by the momentum of Du Bois’ Niagara Movement in 1905, the NAACP fueled a groundswell of activism directed at removing racial discriminatory barriers prevailing at the time. This aligned with the organization’s broader directive of ensuring America’s adherence to the rights guaranteed in the 13th through 15th amendments of the U.S. Constitution.

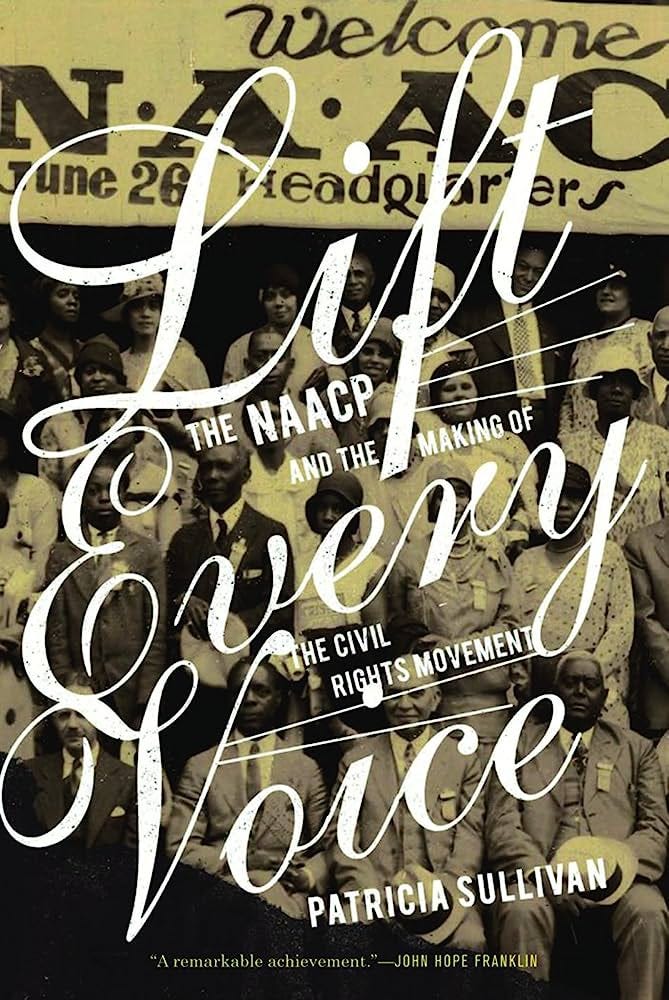

The history of the organization’s formation and evolution in addressing racial discrimination is exquisitely well-captured in the book Lift Every Voice: The NAACP and the Making of the The Civil Rights Movement (2009) by noted University of South Carolina History Professor Patricia Sullivan.

Throughout the book’s pages Sullivan carefully weaves together a mosaic of thought leadership on this celebrated civil rights organization. Highlighting the early decades of NAACP activism, she recounts powerful stories of fearlessness, bravery, and activism by empowered figures like W.E.B. Du Bois, Mary White Ovington, Walter White, Charles Houston, Ella Baker, Thurgood Marshall, and Roy Wilkins. Buoyed by a set of legal victories culminating in Brown v. Board of Education, the book shows the NAACP’s relentless push to dismantle Jim Crow once and for all.

As Sullivan notes in her book:

“The Niagara Movement gave structure and visibility to anti-Washington sentiments shared by a core group of leading place professionals and began the hard work of organizing widespread diddindence into a movement for racial justice. Its platform claimed for “African-Americans” “every single right that belongs to a freeborn American — political, civil, and social” and promised that “the voice of protest of ten million Americans” would “never cease to assail their fellows” until those rights were secured.”

The NAACP, says Sullivan, proceeded forward with establishing a national office in New York City, naming a board of directors as well as Moorfield Story, a white constitutional lawyer as its first president. The only Black American among the organization's leaders at that time was Du Bois.

As Sullivan notes in the opening chapter of her book:

“On August 1, 1910, W.E.B. Du Bois arrived at 20 Vesey Street in downtown Manhattan, home of the New York Evening Post and headquarters of the newly established National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). After more than a decade at Atlanta University, the forty-two-year-old scholar left academic life behind to become director of publications and research for the fledgling organization. Years later, he recalled the sober greeting offered by Oswald Garrison Vuillard, NAACP treasurer and owner of the Evening Post. “I don’t know who is going to pay your salary,” Vuillard announced as Du Bois settled into his bare office.. “I have no money.”

In his ascension to the role of Director of Publications and Research, DuBois in 1910 established The Crisis Magazine which served as the official journal of the NAACP in its Civil Rights crusade.

Over time the publication highlighted the significance of black art, writing, and poetry as a counter - narrative to prevailing racial stereotypes. As a voice for the Harlem Renaissance movement, it featured the literary work of Langston Hughes, Countee Cullenand other noted Black figures of that historical period.

By 1913, the NAACP had become a leading influence in the civil rights movement, expanding its ecosystem of branch offices in key cities like Detroit, Kansas City, Boston, Washington D.C. and Baltimore. Now armed with a rapidly expanding legal team, the organization initiated a series of important court battles where they emerged victorious, boosting its status as a respected legal advocate for racial injustice.

From 1917 to 1919, the NAACP saw a meteoric rise in membership through its over 300 local branches. James Weldon Johnson became the organization's first Black secretary in 1920 while Louis T. Wright, a surgeon, became the first Black Board chairman in 1934.

Sullivan’s book shows how the NAACP ignited a relentless campaign against lynching and other violent atrocities leveled against Black Americans, particularly in the Jim Crow South. To boost these efforts, James Weldon Johnson resigned as the organization’s secretary in 1930 and was succeeded by Walter F. White. Fair skinned and able to pass as Caucasian, White could quietly slip into groups to gather intelligence on activities that may have been detrimental to the NAACP’s racial justice efforts.

In 1935, White brought Howard University law dean Charles H. Houston into the fold as the NAACP chief counsel. Houston’s work on school-segregation cases was a pathway for his protégé Thurgood Marshall’s success in Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, the decision that overturned Plessy v Ferguson.

Sullivan in “Lift Every Voice” also chronicles how the Great Depression of the 1930s had a chilling effect on Black Americans, leading the NAACP to pivot some of its activities towards economic justice. She shows how after years of terse encounters with white labor unions, the Association’s relationship with the newly created Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) buoyed efforts around ensuring access to jobs for Black Americans.

The book explores how White, a friend and adviser to First Lady and NAACP national board member Eleanor Roosevelt, sought out her influence in trying to convince then President Franklin D. Roosevelt to eliminate discrimination in the armed forces and defense industries. Roosevelt ultimately agreed, freeing up thousands of jobs to Black workers when prominent labor leader A. Philip Randolph, in collaboration with the NAACP, threatened a March on Washington movement in 1941. In addition, Roosevelt agreed to establish a Fair Employment Practices Committee (FEPC) to ensure compliance.

During the 1940s, the NAACP witnessed another major uptick in its membership to nearly 600,000 members. With this infusion of membership dues, the organization was able to expand its presence as a legislative and legal force, particularly in terms of its continued advocacy around anti-lynching laws and ending state mandated segregation.

By the 1950s, Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund achieved the groundbreaking milestone of Brown v. Board of Education (1954), which outlawed segregation in public schools. Then came the passage of the Civil Rights Acts of 1957, 1964, and 1968, along with the Voting Rights Act of 1965, all of which the NAACP played an outsized role in.

In the 1950s and 60s, the Civil Rights Movement ignited a new period of activism led by leaders such as Martin Luther King Jr. While generally aligned with the NAACP’s sentiment, a number of movement leaders in King’s circle at the Southern Christian Leadership Conference felt that more intentional, on-the-ground activism was key to keeping the momentum going.

Sullivan’s book “Lift Every Voice” offers a well-researched look at the early foundation of the NAACPs work and the movement it spawned to awaken the consciousness of our nation. Today, the organization remains a pivotal player in the racial justice movement, promoting the legacy of Black opportunity and freedom.

Black Books, Black Minds” is a key foundation of my Great Books, Great Minds” passion project. For me, it’s a labor of love fueled by the endless hours of work I put into researching and writing these feature articles. My aim is to ignite a new world of community, connection, and belongingness through the rich trove of Black History books, thought leaders, and authors we unearth.

So if you are enjoying this digital newsletter, find it valuable, and savor world-class book experience featuring non-fiction authors and book evangelists on Black History themes, then please consider becoming a paid member supporter at $6.00/month or $60.00/year. Large or small, every little bit counts.”