The Rise of Black Women as Power Brokers of Racial Justice

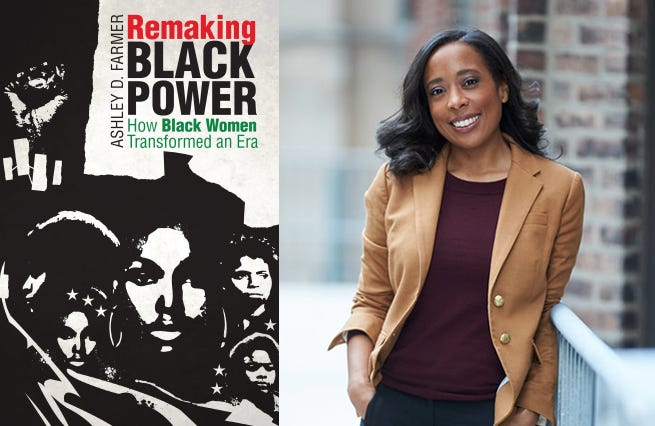

Meet Dr. Ashley Farmer, a noted historian of Black women’s history, intellectual history, and radical politics and Associate Professor in the Departments of History and African and African Diaspora Studies at the University of Texas at Austin.

She is the author of a powerful book entitled Remaking Black Power: How Black Women Transformed an Era, (published in 2017 by UNC Press), which offers the first comprehensive look at efforts on the part of Black women to produce new narratives of Black womanhood as informed by the Black Power Era. As Dr. Farmer says in an early chapter in her book:

“This book documents how activists developed different and at times, competing models of Black womanhood — such as the “Black revolutionary Woman” or the “African Woman” — to advance Black Power tenets and to assert the primacy of women in political organizing.”

In this interview with Black Books, Black Minds, Farmer shares a few thoughts about her journey in writing the book and its significance in today’s continued advancement around Black Power politics.

What was the primary catalyst behind your decision to write “Remaking Black Power?”

This project began with the idea that Black women must have done more than only organize during the Black Power movement. By this I mean that while they did important “on- the -ground” work, I wanted to know if they also produced speeches, pamphlets, articles, etc. that offered their ideas or analyses about their position in the world and how Black Power organizing could change it.

Were there any surprise discoveries for you in researching the book?

When I started this project there were many who suggested that I wouldn't find much. In other words, they wanted me to believe that the men theorized and the women only organized based on these men's ideas. However, when I went into the archives, I found that this was not at all the case. Black women from across regions and organizations joined Black Power organizations not only because they wanted to help their communities, but also because they believed that different formulations of Black Power ideology (self-defense, self-determination, and community control) could help better their lives as black women.

Can you elaborate on what you specifically found?

In particular, I found evidence of their intellectual production — poems, artwork, articles, newspapers —in which they asserted their own theories about racism, sexism, capitalism and how the world could be different. For me personally, it transformed how I saw Black women activists and their role in the movement.

Your book explores how female activists battled for Black Power, inclusiveness, and social justice among other causes by fostering new ideas about womanhood. What in your view is the significance of this movement for modern times?

The women in my book offer two key lessons for modern times. The first is that women were drawn to the movement not just because of the ability to organize on the ground, but also because the central ideologies of organizations like the Black Panther Party, offered them a new way of seeing the world and as well as a vision of how they could engage in liberation.

Second, Black women's ideas of being Black Power organizers were not uniform. These women joined different Black Power organizations (The Panthers, the Congress of African People, the Third World Women's Alliance) based on what the organization had to offer them, not only in terms of on the ground programs, but also ideas about Black women's liberation. All of this offers important reminders about not viewing Black women organizers as a monolith in today's movement work and that the most successful contemporary organizations are ones that offer a broad view of Black women's liberation.

Describe some of the biggest misconceptions that continue to surface with respect to this movement along with the roots of this.

Remaking Black Power offers a few key lessons about the Black Power Movement. First, that the movement was not simply reactionary, anti-white, or violent, as was rooted in negative media portrayals. My book shows that Black Power was not only anti-racist, but rather it was ardently pro-black. By this I mean that organizers were not just interested in critquing the white power structure, but also developing communities, programs, and ways of thinking that supported and celebrated Black life.

Second, the book shows that this movement was far more diverse and widely accepted than many believe. Many people know about groups like the Black Panther Party, but in Remaking Black Power I discuss a range of other local and national organizations that Black women joined. This shows us that thousands of Black women found the movement's central ideas and goals to be really productive and promising for them and their communities.

What is your greatest hope in terms of what readers walk away with from your book? What is the most important message you are seeking to convey?

That Black Power in its simplest terms means the ability to be empowered, lead, and decide what is best for one's own community and self as well as to defend one's self and community against intellectual, social, economic, and violent attacks. Moreover, I wanted to show that the movement was successful in reshaping how Americans think about Black life, politics, communities, and progress today. And finally, that the movement could not have been as successful as it was without Black women thinkers and organizers.

“Black Books, Black Minds” is a critical piece of my “Great Books, Great Minds” passion project, a labor of love fueled by the endless hours of work I put into researching and writing these feature articles. So if you enjoy this digital newsletter, find it valuable, and savor world-class book experiences featuring non-fiction authors and evangelists on Black History themes, then please consider becoming a supporting member.