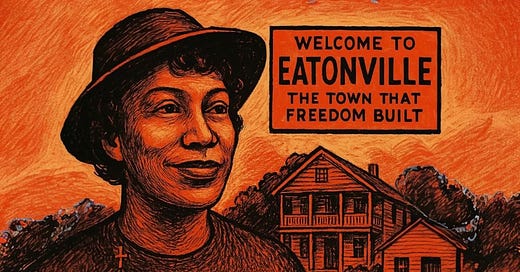

I’ve never set foot in Eatonville, Florida. Never walked its streets, never visited the Zora Neale Hurston Museum, and never stood on the soil Joseph Clark, the founding father and second mayor of Eatonville, once purchased in a bold act of defiance and hope. And yet, it feels like I’ve been there many times.

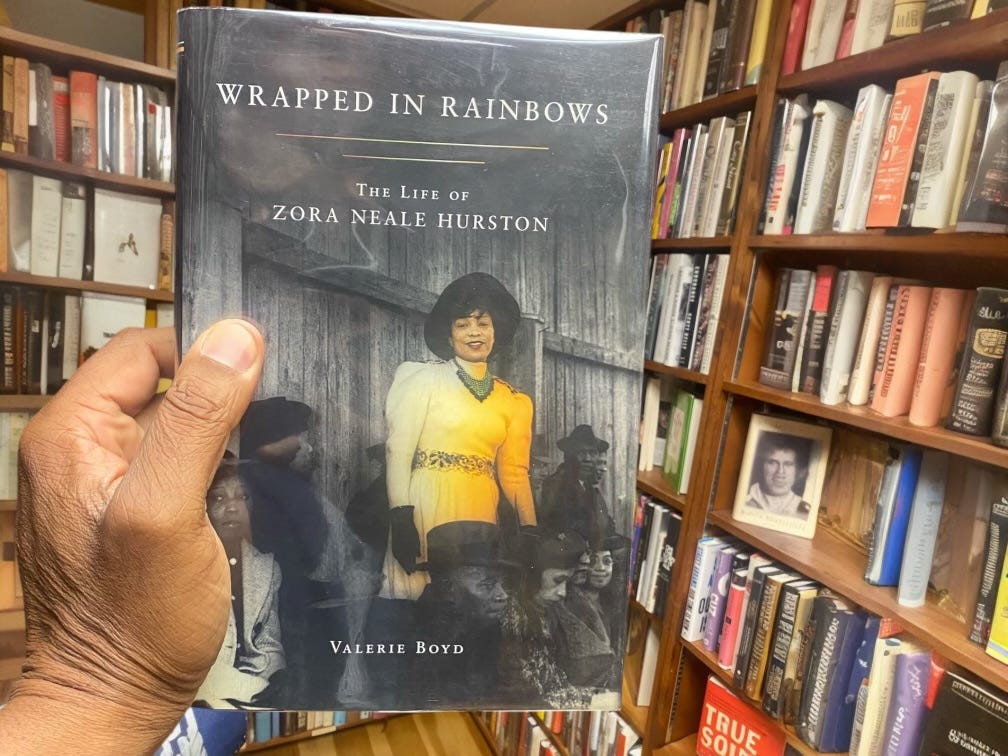

The spark behind this essay came as I was reading Wrapped in Rainbows: The Life of Zora Neale Hurston by Valerie Boyd, a magnificent biography that reanimated the lore and light of Eatonville through Hurston’s eyes. Chapter after chapter, I was drawn not just to the brilliance of Zora Neale Hurston, but to the idea of Eatonville itself—America’s first incorporated Black town, a place that seemed to whisper to me from the margins of history, inviting me to listen more deeply.

So I followed that whisper into the archives, into oral histories, into maps and memoirs and digital records. What I found was not just a footnote to American history, but a declaration. Eatonville wasn’t merely a place. It was a possibility. A radical, visionary possibility made real by people who believed they were worthy of governing themselves. This is their story and how Zora helped bring it to fruition.

Founding Freedom: Eatonville in the Post-Reconstruction Era

To understand the significance of Eatonville, we must first understand the time in which it was born. The year was 1887. The promise of Reconstruction had collapsed under the weight of white backlash, systemic terror, and Supreme Court betrayals.

Black Americans, many only recently emancipated, were being pushed out of political life, subjected to violence, and denied access to land and wealth. In this bleak backdrop, the very act of founding a Black town was nothing short of revolutionary.

Joseph Clark, a formerly enslaved man with vision and grit, helped make it happen. With the assistance of sympathetic white landowners like Josiah Eaton and Lewis Lawrence, Clark helped establish a parcel of land just north of Orlando where Black people could own, build, and thrive. On August 15, 1887, 27 Black men who were eligible voters met to incorporate the town, elect its officials, and name it Eatonville in honor of one of the white allies who had sold them the land.

The significance of that act? Monumental. This was not a colony or a segregated quarter. This was an incorporated town, self-governed by Black people. Eatonville was born not out of charity but out of necessity and self-determination. It was an act of liberation as radical as any march or lawsuit.

In Eatonville, Black men and women could live outside the daily brutalities of the Jim Crow South. They could own homes, govern themselves, and send their children to school with hope rather than fear.

Zora Neale Hurston: Eatonville’s Storyteller and Spirit

You cannot write about Eatonville without invoking the voice that carried it into immortality—Zora Neale Hurston. Though born in Notasulga, Alabama, Hurston always claimed Eatonville as her home. And for good reason. Her father, John Hurston, became the mayor. Her formative years unfolded under the Florida sun, surrounded by Black excellence in every form, from the preacher at the AME Church to the women who wove magic through everyday gossip.

Zora called Eatonville her “native village,” and in many ways it was. In her seminal essay “How It Feels to Be Colored Me,” she writes, “I remember the very day I became colored,” noting that it wasn’t until she left Eatonville for Jacksonville that she experienced racism in its rawest form. Eatonville had been a shield, a town where Blackness was not defined in contrast to whiteness, but stood on its own, radiant and sufficient.

Her literary works draw deeply from Eatonville’s well. Their Eyes Were Watching God, Mules and Men, and many of her short stories immortalize the porch talkers, conjure women, and self-governing institutions of Eatonville. Her anthropological work captured the oral traditions of the town, making folklore into literature and everyday speech into sacred text. Without Eatonville, there would be no Zora. And without Zora, the world may never have known Eatonville’s full glory.

The Architecture of a Black Utopia: Church, School, Self-Governance

Eatonville’s early years were rooted in two institutions that reflected its community’s values: the church and the school. Before a single home was built, land was set aside for the St. Lawrence African Methodist Episcopal Church in 1881. Faith was foundational but not in the abstract sense. The church was Eatonville’s gathering place, its social nexus, its heart.

Education, too, was central. In 1889, the Robert Hungerford Normal and Industrial School was established. It was modeled after Booker T. Washington’s Tuskegee Institute, blending vocational training with academic education. At a time when Florida denied even basic education to most Black children, the Hungerford School became a beacon. It was one of the few places where Black youth could imagine a future shaped by knowledge and skill rather than labor and servitude.

Together, these institutions anchored Eatonville’s ethos of self-help, dignity, and collective progress. They were not only shields against the outside world but also engines of inner development.

Eatonville’s Role in the Broader Black Town Movement

Eatonville was not alone in the dream of Black autonomy. Across the U.S., from Mound Bayou, Mississippi, to Boley, Oklahoma, Black communities took root. But most were eventually erased by economic sabotage, racist violence, or urban renewal policies masked as progress.

Eatonville endured.

It is one of fewer than a dozen Black-governed municipalities from the 19th century that still exist. That’s not just a historical quirk, it’s a miracle. It survived through land grabs, underfunding, and political marginalization. As preservationist and architect Everett Fly once noted, Eatonville was a “living blueprint” for Black self-governance, proof that a town could be built on Black labor, led by Black vision, and sustained by Black faith.

Its survival offers both inspiration and instruction. Eatonville teaches us that freedom isn’t always declared with trumpets. Instead it is often carved into land, voted into office, and sung from porches under the stars.

Cultural Resurrection: How Eatonville Honors Its Past

Eatonville has not only preserved its past, it has animated it. Today, the town is a cultural hub. The Zora Neale Hurston National Museum of Fine Arts, affectionately known as “The Hurston,” stands as a monument to the town’s most famous daughter and a beacon for Black artists and intellectuals. More than an exhibit space, it is a pilgrimage site.

Each January, Eatonville hosts the Zora! Festival, a celebration of arts, heritage, and scholarship. It’s not just a street fair, it’s a full-scale cultural symposium. Scholars from around the world convene here. Black artists perform here. And Eatonville becomes, once again, a center of gravity for the African diaspora.

When I read about the festival, I found myself wondering—what if more towns across the country did this? What if history weren’t something we preserved behind glass but something we danced to, debated in real time, and lived out loud?

Sacred Land and the Struggle for Preservation

Even as Eatonville celebrates its heritage, it continues to fight for its future. In recent years, development pressures have threatened to erode its most sacred spaces, chief among them the former campus of the Hungerford School. Plans to sell parts of the land to private developers met fierce resistance from residents, who rightly saw it as the possible erasure of a legacy.

Thanks to local activism and national support, including a $200,000 grant from the African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund, Eatonville is pushing back. The town is now exploring sustainable development options that protect its character while creating economic opportunity. But the battle is not over. As one local leader put it: “We’re not just fighting for land. We’re fighting for memory.”

That hit me hard. Because memory, unlike monuments, can disappear if we’re not vigilant. Eatonville is sacred ground. Not just for Floridians. For all of us.

The Eatonville Resonance in Today’s America

In an age where debates about race, history, and identity are more intense than ever, Eatonville offers clarity. It reminds us what’s possible when a community dares to define itself on its own terms. It challenges the myth that Black excellence must always be exceptional, as if it cannot be collective. Eatonville says: Black people have always been capable of governing, building, and thriving if given the space.

It’s tempting to see Eatonville as a relic. But I don’t. I see it as a blueprint.

As we think about reparations, justice, and racial reconciliation, towns like Eatonville offer something money cannot buy: proof. Proof that Black autonomy isn’t just a dream—it has been, and still is, a reality. The question is whether America will finally make room for it to flourish.

A Final Reflection

I still haven’t been to Eatonville. But I will go. I’ll walk its streets, visit The Hurston, and maybe sit on a porch and imagine Zora watching me with her sly smile and pen in hand. But even if I never make it there, Eatonville has already visited me. Through the pages of a book. Through the echoes of its founders. Through the steady rhythm of its survival.

Some places don’t need to be large to be legendary. Eatonville is one of them. It may be small on the map, but it is monumental in meaning. And for that, I am grateful.

If you are finding “Black Black, Black Minds” to be a valuable resource in learning about Black History , then please consider supporting my work by subscribing as a paid member or tipping me some dirty chai latte love.

No paywalls—just raw, well-researched feature articles delivered straight to your inbox. Every contribution helps keep this journey alive. you contributions will be greatly appreciated.

Diamond Michael Scott, Global Book Ambassador

Zora Neale Hurston died in Ft. Pierce Florida in 1960. Vero Beach, where I attended an all-white school in a segregated state, was less than fifteen miles away. I learned about Zora Neale Hurston’s existence years later, she being a writer whose reputation only rose decades after her death in obscure poverty. Florida school curriculums would not have included anyone like her at that time. In 1960 I was sixteen, thinking I was a writer, and the fifteen miles between me and one of the great writers of the 20th century might as well have been fifteen thousand.