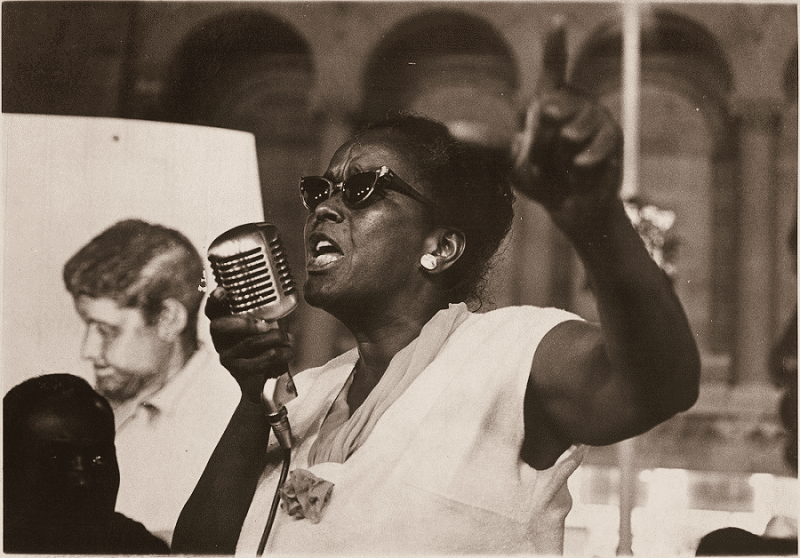

The Trailblazing Work of Civil Rights Activist Ella Baker

“In order for us as poor and oppressed people to become a part of a society that is meaningful, the system under which we now exist has to be radically changed. This means that we are going to have to learn to think in radical terms. I use the term radical in its original meaning—getting down to and understanding the root cause. It means facing a system that does not lend itself to your needs and devising means by which you change that system.”

Ella Baker, 1969

Black activist Ella Baker (1903 – 1986) career spanned more than five decades, working shoulder to shoulder with some of the most noted civil rights leaders of our time, including W. E. B. Du Bois, Thurgood Marshall, A. Philip Randolph, and Martin Luther King Jr. Recognized as one of the most influential women leaders of the twentieth century, Baker’s activism spanned fifty years and touched an endless number of lives.

When it came to human rights and economic freedom, one would never accuse Baker of being taciturn. With an ability to inspire even the most somnolent of crowds, she deftly championed grassroots organizing, radical democracy, and initiative to uplift the oppressed.

Biographer Barbara Ransby has referred to Baker as "one of the most important American leaders of the twentieth century and perhaps the most influential woman in the civil rights movement"

Ella Jo Baker was born on December 13, 1903, in the coastal town of Norfolk, Virginia. Reared in North Carolina, she acquired a fervent interest in social justice during her early years due in part to hearing her grandmother’s stories about slavery.

While a slave, her grandmother recounted painful stories of having been whipped for refusing to marry a man chosen for her by the slave owner. It was her grandmother’s pride and resilience amid this racism and harsh treatment she endured that inspired Baker throughout her life.

Baker’s maternal grandparents purchased, resided on, and cultivated land that was formerly a part of the plantation where they were enslaved. This became a great source of pride for the family as they, in ensuing years, became successful farmers.

Ella did her college studies at Shaw University in Raleigh, North Carolina. While a college student, she often challenged school policies that she believed were unfair. After graduating in 1927 as class valedictorian, Baker relocated to New York City where she became involved with various social activist organizations.

During the 1930s, she connected with the Young Negroes Cooperative League, whose mission was to fuel Black economic power through collective planning. Her economic justice mantra at the time was:

“People cannot be free until there is enough work in this land to give everybody a job.”

In 1940, she became involved with the NAACP as a field secretary. She later served as director of branches from 1943 until 1946.

In her book Lift Every Voice: The NAACP and the Making of the Civil Rights Movement , noted author, historian and William Arthur Fairey II Professor of History at the University of South Carolina Patricia Sullivan recounts:

“Ella Baker brought a rare combination of intellect, experience, and talent to the NAACP at a transitional moment in its history. Raised in the small town of Littleton in eastern North Carolina, she had deep southern roots. Her political consciousness and social activism, however, were forged in Depression-era New York…

She moved to Harlem after completing college and found a “hotbed of radical thinking. Baker immersed herself in the city’s vibrant intellectual and political movements and worked in a variety of activities and organizations, such as the Young Negroes’ Cooperative league, the Young People’s Forum, and the Workers Education Project of the Works Progress Administration, filling in wit freelance journalism and odd jobs to pay the rent.”

Sullivan added that “for Baker, as for others of her generation, the Depression had exposed the vulnerability of the individual to broad economic and social forces and elevated the essential role of collective action for securing the welfare of workers, consumers, and other groups.”

Inspired by the 1955 historic Montgomery bus boycott, Baker co-founded In Friendship, an organization aimed at raising money to battle the prevailing Jim Crow laws of the Deep South. Two years later, she relocated to Atlanta to help organize Dr. Martin Luther King’s new organization, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). She also ran a voter registration campaign called the Crusade for Citizenship.

Baker left the SCLC after the infamous Greensboro sit-ins with a new interest in supporting the growing number of student activists involved in the civil rights movement. She started and led a gathering at Shaw University for student leaders involved in the 60s sit-ins. This led to the birth of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) which served as the epicenter of student commitment to the civil rights movement during the 1960s.

Employing a Gandian approach of nonviolent direct action, SNCC members joined activists from the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) to coordinate the 1961 Freedom Rides. Four years later, SNCC helped ignite Freedom Summer, an effort to direct national attention towards the atrocity of Mississippi’s racism and efforts to stymie Black voter registration.

Ella Baker’s impact is symbolized by the nickname she acquired: “Fundi,” a Swahili word meaning a person who teaches a craft to the next generation. She continued her legacy work as a strong advocate for human and civil rights until her death on December 13, 1986. She was 83 years old.

In the book “Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement: A Radical Democratic Vision,” biographer Barbara Ransby chronicles Baker's profoundly inspiring work as an organizer, an intellectual, and a teacher, from her early experiences in depression-era Harlem to the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s. Ransby highlights how Baker was a complex figure whose radical, democratic stances on Black poverty fueled through a grassroots leadership approach brought a unique voice to the civil rights movement. Further, the book offers a broader look at how the Black American fight for justice intersected with other progressive struggles during the twentieth century.

In the book’s introduction, Ransby noted:

“Ella Baker spent her entire adult life trying to “change that system. Somewhere along the way she recognized that her goal was not a single “end” but rather an ongoing “means,” that is, a process. Radical change for Ella Baker was about a persistent and protracted process of discourse, debate, consensus, reflection, and struggle. If larger and larger numbers of communities were engaged in such a process, she reasoned, day in and day out, year after year, the revolution would be well under way…..

Ella Baker understood that laws, structures, and institutions had to change in order to correct injustice and oppression, but part of the process had to involve oppressed people, ordinary people, infusing new meanings into the concept of democracy and finding their own individual and collective power to determine their lives and shape the direction of history.”