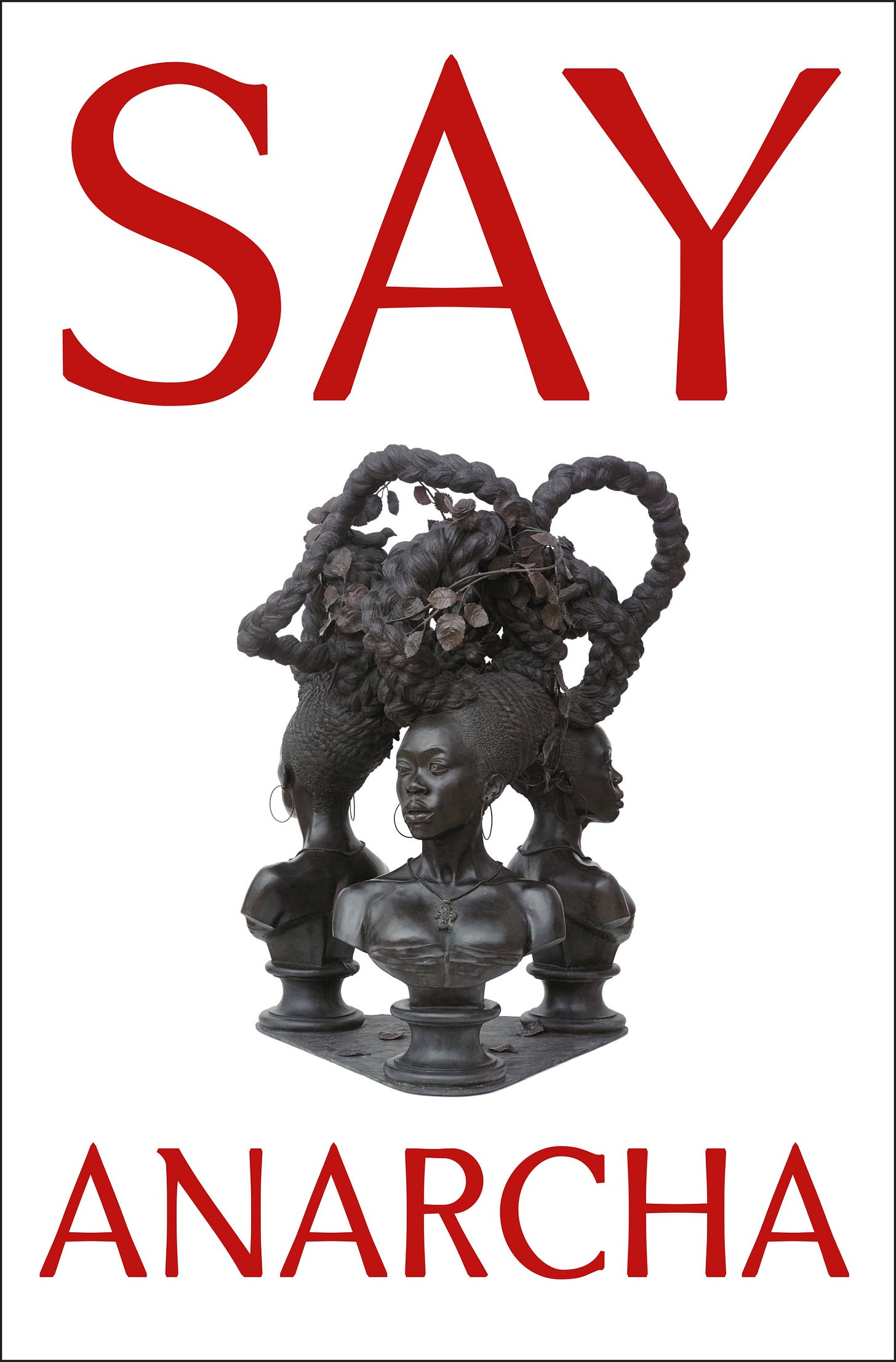

The Unimaginable Suffering of Three Enslaved Women

How Their Story Informed The Women’s Health Movement

Illustration of Dr. J. Marion Sims with Anarcha by Robert Thom: Pearson Museum, Southern Illinois University School of Medicine

By Guest Contributing Writer Marc S. Friedman

Who was Dr. J. Marion Sims? Was he a brilliant, innovative, and visionary 19th Century gynecological surgeon, recognized throughout America and by many Europeans as the “Father of Modern Gynecology?”

Or was Dr. Sims, though a gifted surgeon, a self-promoter in the image of P.T Barnum who deliberately concealed his surgical failures, and the deaths he caused to women, to gain fame and fortune?

“Say Anarcha”, by J.C. Hallman, attempts to answer these questions.

In the 1840’s, Sims, then practicing in Montgomery, Alabama, developed a tool and a technique for treating enslaved women who suffered from a condition known as a vesicovaginal fistula.

Typically this results from prolonged labor in which the pressure from the fetus’s skull reduces blood flow. As a result, the surrounding tissue dies, creating an open channel between the mother’s bladder and vagina that allows for the continuous involuntary flow of urine into the vaginal cavity and then beyond.

The potential loss of the child is agonizing for sure. But the calamity is exacerbated by the loss of urinary and fecal control. This is a devastating condition with psychological and emotional consequences as well as physical ones.

When an enslaved woman suffered such a catastrophic injury, her value as a slave was substantially diminished. In addition to constantly emitting noxious odors, a woman with this condition would be significantly disabled and therefore unable to pick cotton and perform other physically demanding tasks in the plantation’s cotton fields.

In some instances, the enslaved woman could no longer procreate, thereby depriving the Master of future slaves to work the plantation or to be sold.

In the 1840’s, Dr. Sims, who had not been interested in “looking inside women” as he wrote, began to experiment with three enslaved women – Anarcha, Betsey and Lucy – who suffered from fistulas.

Through his repeated efforts to find a cure for fistulas, Sims experimented on these and other enslaved women. He developed a double-bladed surgical instrument called a “vaginal speculum” that enabled Sims to examine the vagina and cervix. He also began using silver wire to stitch up the vagina where necessary. It should be noted that anesthesia was in its early infancy and these surgeries were conducted without any anesthesia, and without the consent of the patient.

Anarcha had over 30 painful surgeries. While Sims claimed that he had successfully cured Anarcha’s fistulas, he had failed. However, by happenstance Sims encountered the famed American showman and businessman P.T. Barnum who befriended Sims. Barnum gave Sims advice on how he could promote himself to be the renowned expert in gynecological surgery using Anarcha’s alleged “cure” as a springboard.

Barnum told Sims that with a carefully-orchestrated campaign Sims would become a legend. Following Barnum’s advice, Sims gave speeches in America and Europe, wrote and published medical papers, gave interviews, and did all he could to promote his reputation and gain fame and fortune.

However, Sims lived in constant fear that someday the medical community and others would learn that Anarcha, who had been sold to successive plantation owners and thought to disappear, was never cured.

The book author J.C. Hallman did a prodigious amount of research to skillfully tell the frightening and disturbing life story of Anarcha, and the painful and unsuccessful surgeries she endured. But the author also tells the story of Dr. Sims and his often unsuccessful surgeries on enslaved persons as well as wealthy White women, many of whom died.

In fact, as a result of Sims’s purported achievements, including establishing a Women’s Hospital in New York City, a statue of Sims was erected in New York City’s Central Park and in two other locations in the South including Montgomery, Alabama, where Sims started his experimentation on enslaved women in his backyard “operating room.”

But in the 1970’s, Sims’s reputation began to suffer as more facts concerning his career started to come to light. As a result, beginning around 2010, protestors in New York City began calling for the removal of Sims’s statue. In 2018, the statue was relocated to Green-wood cemetery in Brooklyn, where Sims is buried.

This is an important, searing and disturbing book. It calls to mind the medical experiments conducted in the notorious Tuskegee Syphilis Study between 1932 and 1972 on 600 impoverished Black sharecroppers from Macon County, Alabama.

“Say Anarcha” also reminds one of “The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks” by Rebecca Skloot, which is also disturbing. Lacks was a Black woman from Baltimore with ovarian cancer. Unbeknownst to her, while at Johns Hopkins Hospital, Lacks cancer cells were taken away to become the source of the HeLa cell line, one of the most important cell lines in medical research.

To be fair, Sims has many supporters who refute the claims made in “Say Anarcha” and elsewhere concerning the alleged unethical conduct of Sims. His most prominent defender is Lewis Wall, a Professor of Sociocultural Anthropology, Obstetrics and Gynecology at Washington University in St. Louis. In a well-researched 2006 paper, Wall states,

“The evidence suggests that Sims’s original patients were willing participants in his surgical attempts to cure their affliction – a condition for which no other viable therapy existed at the time.”

Wall also offers a defense to the charge that Sim’s committed wrongdoing by not administering anesthesia to Black patients such as Anarcha and others. It had been alleged that in Sims’s opinion Black people didn’t feel pain like Whites do.

In Sims’s defense, Wall argues that anesthesia was not widespread in 1845 and that surgeons who had been trained without the availability of anesthesia preferred their patients to be awake.

No doubt the ethics of Dr. Sims’s fistula surgeries were highly questionable. I recommend that once a reader has finished “Say Anarcha”, they also read Professor Wall’s article that is available at:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2563360/.

The reader can decide for themselves whether Professor Wall’s defenses of Sims are persuasive.

As noted earlier, one of the statues honoring Sims stands at the Alabama State House in Montgomery. Sims began his gynecological surgery and treatment of fistulas in Montgomery. That is where he encountered Anarcha, Lucy and Betsey who were among the earliest of his gynecological patients and the subjects of his experimental surgeries.

As other researchers correctly observed, these enslaved women were overlooked. Thus in 2021, a new monument was unveiled in Montgomery to tell the other side of the story and to honor Anarcha, Lucy and Betsey as the “Mothers of Gynecology” for their special contributions to gynecological surgery. These three brave women, who fell into the crevices of history, changed the world and will be forgotten no more.

A few years back while still living in Denver, our local NPR station featured a Black poetess whose topic was to speak as Anarcha. At that point I'd not known the history. Her recital was so raw that I very nearly wrecked the car into a ditch. It was history that most of us, most especially White women, don't know. I've written about it since as a way of propagating that awareness, and in fact did that very thing again today on LInked In when I saw a mention of Sims' name. I was very glad to see this:

https://www.vox.com/identities/2018/4/18/17254234/j-marion-sims-experiments-slaves-women-gynecology-statue-removal

Still, most of us are clueless. The more alt-history that's peeled away, the more horrific this Nation's role in brutality. And to think Nikki Haley had the audacity to say we aren't a racist nation. I nearly choked on my coffee. The level of denial boggles the mind.

Thank you for posting this article.