"We shouldn’t need legislation for our hair. Nobody else needs it.”

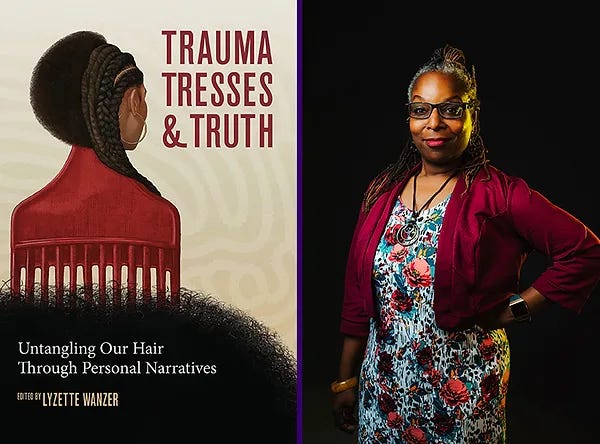

Lyzette Wanzer, editor of Trauma, Tresses, and Truth: Untangling Our Hair Through Personal Narratives

Black hair is a complex issue, one that has historically been full of entanglements. Those who wear hairstyles as a form of racial and cultural expression have long faced stigmatization and stereotypes among dominant cultures. Much of this is rooted in the vestiges of slavery, where higher status was often given to slaves possessing straighter hair and lighter skin.

In the mid 20th century, Madam C.J. Walker, widely regarded as America’s first female self-made millionaire, brought awareness to the Black hair movement with advertisements for dressing that could tame “kinky, snarly, unruly” hair.

Then came Black Power movement of the 60’s and 70s when activist and racial justice icon Angela Davis and others used Afro hairstyles as a political statement in direct defiance of Eurocentric beauty standards.

Controversy around Black hair still exists to this day. Black and Brown people have experienced restrictive workplace practices, been fired from jobs, been expelled from schools and experienced persistent oppression based on how they choose to wear their hair. Even in cases where institutional protections against race-based discrimination are in place, Black women in particular have faced the lion's share of abusive practices in terms of hair bias.

Fortunately, there has been some momentum in recent years to address these issues. By way of example, California in 2019 became the first state to pass legislation protecting people from hair discrimination. Known as the CROWN Act, it offers protections against race-based hair bias with safeguards against discrimination involving hair texture and protective styles, including braids, twists, and locs. Although other states have adopted similar legislative statutes, progress has been slow in efforts to ban it at the federal level.

In the book Trauma, Tresses, and Truth: Untangling Our Hair Through Personal Narratives, curated and edited by San Francisco writer, editor and writing instructor Lyzette Wanzer, readers gain deep insights into the struggles that women of color and even men experience in workplace and other settings when their natural hair is weaponized against them. I recently had the opportunity to talk with Wanzer about her own life journey and what inspired her to pursue this critical important piece of work around the hair movement for Black and Brown individuals.

Please share a little about your life story and how the power of books have informed your journey.

I have been writing stories since childhood, an avocational by-product of being an avid reader and a sickly child who missed many school days. During those early latchkey years, I read every book and magazine in the house: mine, my younger sister’s — and my parents’, including several forbidden texts tucked away in their bedroom closet’s dark corners.

Those illicit volumes were certainly intriguing reads, but in the end it was the innocuous Five Little Peppers and How They Grew that roused me. I took the character of nine-year-old Joel Pepper, on whom I had a crush, and gave him his own story. I was a voracious reader and filled tens of notebooks with handwritten stories over the years.

Were there other books that resonated with you during your early formative years?

Other childhood books that inspired me include Tuck Everlasting, The Secret Garden, The Chronicles of Narnia, Where the Red Fern Grows, The Catcher in the Rye, The Outsiders. As I grew into young adulthood my inspirations included books like Black Boy, Wouldn't Take Nothing for My Journey Now, We Were the Mulvaneys, The Bluest Eye, Six Memos for the Next Millennium, and quite a bit of nonfiction. I remember Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Black Man making a huge impression on me.

What ultimately led you to pursue the narrative around Black women and the complex and convoluted relationship they have with their hair?

The book idea was catalyzed by several audience members at the 2020 AWP Conference in San Antonio, where I had curated and presented a panel on Black women and natural hair. Six women came up at the close of the panel and asked where the correlating book was. Of course, there was no book. While at first I wasn’t convinced that the idea had any legs as a book, that year's Summer of Racial Reckoning following the Breonna Taylor and George Floyd assassinations changed my mind.

Can you elaborate a bit further on this point?

My thinking was that the policing and persecution of our natural hair is yet another form of oppressing and misreading the Black body. I spent much of that summer being extremely enraged, my days fraught with unhealthy, unrelieved gavel-to-gavel fury that leaked into and compromised my everyday functioning. The coronavirus lockdown exacerbated the situation. The one weapon I could wield was my pen. When national demonstrations approached an acute zenith, I began writing a book proposal.

What was this experience like?

It was a sound way for me to channel my anger and sense of impotence. It was also a way for me to surface the erasure of Black and Black Latina women and girls in the police reform and Black Lives Matter movements.

Here, it’s important to note how Black and Black Latina women’s injustices have been largely subordinated to those of men in these movements. Beyond Breonna, beyond Sandra, there’s Korryn Gaines, Tanisha Anderson, Michelle Cusseaux, India Kager, and so many others who seldom draw the same journalistic attention as Tamir Rice, Eric Garner, Alton Sterling, Michael Brown, or Philando Castile. As a topic at the intersection of racial injustice, Black feminism, and the need for course correction, a book on natural hair seemed potent, apropos, timely, and curative.

Describe your biggest surprise discoveries in terms of the stories that you curated, edited and featured in Trauma, Tresses, and Truths?

I gained quite a lot of insight into the additional complexity layer Afro Latinas contend with in terms of the "pelo malo" issue, often within their own families. These women are both Black and Latina in a society that generally expects them to choose one side or the other, and they often experience acute colorism and texturism from their nuclear and extended family members-- especially if they have a darker skin tone or more curly, nappy hair than their siblings or cousins. I learned that anti-Black sentiment and denial of African roots is not uncommon among Afro Latino populations, both here and in places like the Dominican Republic, Brazil, and Puerto Rico. It's an additional layer of colonized-informed trauma on top of the cultural violence all Black women face with regards to their natural hair.

What words best reflect your journey to this point in your writing and teaching career?

Persistence, perseverance, a thick skin in the face of rejections, being a risk taker, and self-belief. Also, being a good literary citizen: being involved in the larger literary community outside of myself, such as volunteering at events, attending other writers' readings, supporting other authors on social media, participating in open mics, networking at conferences, uplifting other authors' books, and understanding the import of building and maintaining networks. All of these qualities and aspects played a role in advancing my writing career over the years.

Are there any lessons that you share with your writing students regarding these experiences?

I tell my students that, besides talent and persistence, one of the most important qualities they need to possess if they aim for a professional literary career is a thick skin. If you fold and deflate easily under rejections, you should relegate writing to a hobby or avocation rather than as a professional aspiration. This isn't just true for writing, but for all of the arts.

Are there any Black women authors or books that hold special significance to you in terms of your life and career evolution?

Adichie's We Should All Be Feminists, Mary-Frances Winters' Black Fatigue, and Shonda Buchanan's Black Indian are all books that fit the "special significance" category. Perhaps surprisingly, I also want to mention Harryette Mullen's poetry. While I read individual poems much more often than I read entire books of poetry, Mullen's work has served as a model for several of my creative nonfiction pieces. I feel like her poetry invited me — or granted me permission somehow — to stretch and extend the boundaries of my work, even though I was writing prose.

An Invitation from Diamond-Michael Scott

“Black Books, Black Minds” is a key foundation of my Great Books, Great Minds” passion project. For me, it’s a labor of love fueled by the endless hours of work I put into researching and writing these feature articles. My aim is to ignite a new world of community, connection, and belongingness through the rich trove of Black History books, thought leaders, and noted authors

So if you are enjoying this digital newsletter, find it valuable, and savor world-class book experience featuring non-fiction authors and book evangelists on Black History themes, then please consider becoming a paid member supporter at $6.00/month or $60.00/year.

Thank you. In the meantime stay thirsty for a great book