Reviewed by Contributing Writer Marc S. Friedman

Many books have been written about the White working class and its impact upon the building of America in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Among these books is the recently-published “Hillbilly Highway: The Transappalachian Migration and the Making of a White Working Class” by Max Fraser.

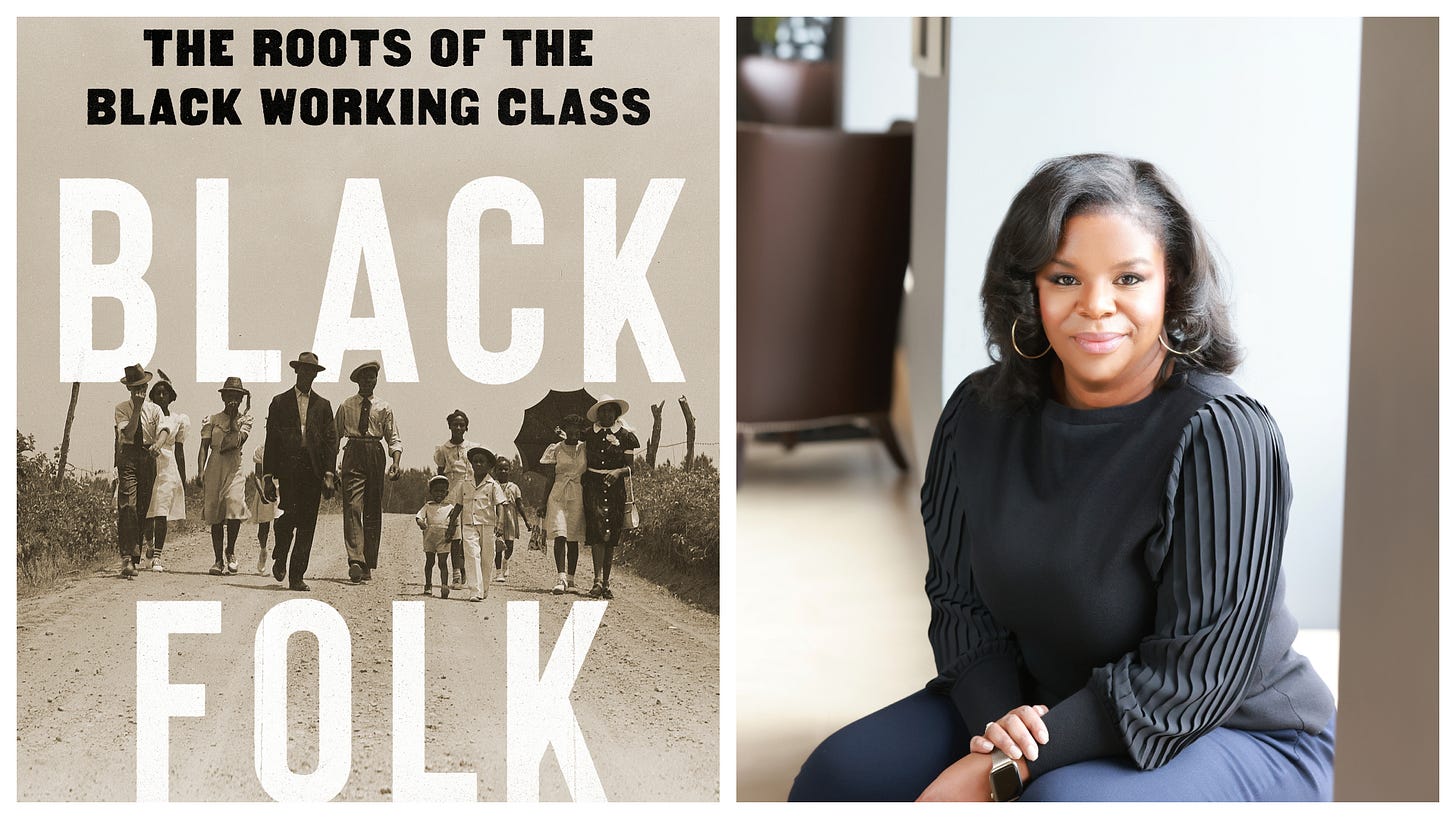

Blair LM Kelley’s new book “Black Folk: The Roots of the Black Working Class” about the Black working class and its contributions to the building of America is intended to be a strong counterpoint to the traditional argument that Blacks were simply laborers or domestic workers who added little to the foundation and growth of the American economy. Kelley, a professor at the University of North Carolina, argues persuasively that the labors and very existence of everyday Black workers have been all too often overlooked.

Using her own multi-generational family’s history as a backdrop, Kelley traces the history of the Black worker over a 200-year period, spanning from her enslaved ancestor Henry, a plantation blacksmith, to the Black Amazon, Instacart and Fed-Ex delivery drivers, hospital and senior care workers, food preparers, bus drivers and others who were deemed “essential workers” during the Covid-19 pandemic.

The author’s essential thesis is that members of the Black working class were consistently and unfairly marginalized, devalued, abused and ignored. Through her prodigious research, Kelley has assembled compelling evidence to support this argument.

The author first focuses on the trials and tribulations of enslaved persons in the early 19th Century, including her own ancestors such as Henry the blacksmith. She then discusses Black workers after the Civil War. These included washerwomen and laundresses, field hands, housemaids, Pullman porters, postal workers and others who frequently were abused, underpaid, sexually assaulted, physically punished, and demeaned by the White families and others for whom they toiled.

Kelley persuasively argues that these disadvantaged Black workers were essential to our Nation’s basic functions. Yet, they were dehumanized. Often their White employers would not even know the Black workers’ names. To these Whites, calling the men “boys” or the women “mammies” was sufficient.

After Emancipation, and despite the crushing burdens of Jim Crow laws and de facto racial discrimination, the Black working class consistently searched for ways to embrace their newfound freedoms. To do this, communities of Black workers sprung up throughout America.

In most Black communities, churches were the focal point. There the congregants and other Black Folk from the community would gather, outside the earshot of Whites, to discuss their living conditions, dreams and plans. The church was a place where they could laugh, cry, commiserate with one another, and criticize their White employers without fear of retribution and punishment. This indomitable community spirit was expressed as well on street corners, in backyards, and in barbershops.

Throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Black folks’ networks of resistance to continuing White oppression grew. They helped members of their communities with food and clothing, medical care, child care and other types of support. These communities welcomed Blacks who had come from rural areas to Southern cities such as Wilmington, NC and Memphis.

Once the Great Migration to the North began around 1915, Black communities sprung up in cities such as Philadelphia, Baltimore, Pittsburgh and Los Angeles. Blacks living in these cities would provide whatever assistance they could to the newcomers from the South.

However, the Black churches provided much more than “gripe sessions” for the Black working class. They were also places where the workers could secretly plan political actions and labor strikes to have an impact on policies relating to better pay and working conditions.

A poignant example was the washerwomen’s strikes. These workers wanted to be treated like human beings and not chattels. They desired better pay and working conditions, time off, reasonable hours and more. They no longer were willing to work in their White employer’s homes. They demanded they be allowed to take the laundry to their homes, where they could watch their children. By organizing, though not in a formal labor union, these brave and inspirational Black women achieved many of their goals.

Many of the Black labor unions and similar organizations developed in the early 20th century in part because existing labor unions were Whites-only. One prominent Black member union was the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. Under the leadership of the legendary A. Philip Randolph, the porters gained considerable economic influence through their labor actions, thereby improving their working conditions, wages and benefits.

One especially interesting chapter deals with the emergence of the U.S. Post Office (now the U.S. Postal Service) as a major employer of working-class Blacks. Kelley describes how President Wilson, an unabashed racist, worked hard to exclude Blacks from post office jobs. But Blacks seeking employment with the Post Office were indefatigable.

In 1920, as a result of President Woodrow Wilson’s segregationist policies, there were less than 4,000 Black mail carriers and postmasters. Many postmasters were murdered, injured or run out of town by White racists.

One example of the racism in the Post Office was the requirement that each application for employment be accompanied by a photo of the applicant that started during President Wilson’s Administration. The purpose, of course, for this requirement was that it would enable the hiring officer to see which applicant was Black so that White applicants could be chosen.

The Black-dominated National Alliance of Postal Employees persuaded President Franklin Delano Roosevelt to change this rule in November of 1940. Roosevelt also “ordered that the rules governing civil service appointments be changed to prohibit discrimination. While this significant rule change did not immediately end the baked-in discrimination against Black applicants, it did signal that the future for them looked much brighter.

By 1950 there were more than 45,000 Black postal workers. Eventually the U.S Postal Service became the largest and most important employer of Black working men and women in America. For them these were secure and highly respectable jobs, with fair pay, an opportunity to advance, and excellent benefits.

Like the Black-led Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the National Alliance of Postal Employees did much more than traditional labor unions. Through their labor strikes and other activist actions, these two organizations began to fundamentally expand the opportunities for the Black working class in America.

Kelley writes with intelligence and authority. Based upon prodigious research and with deep insights, the author accomplishes her mission, which, as she states, is this:

“Black Folk attempts to capture the character of the lives of Black workers, seeing them not just as laborers, or members of a class, or activists, but as people whose daily experiences mattered -- to themselves, to their communities, and to the nation at large, even as it denied their importance.”

As the author writes, in today’s America the term “working class” has come to largely mean ruddy white men in hardhats or waitresses in a rural dinner, seemingly left behind as the World goes through monumental changes.

Kelley states the the words ‘working class’ are synonymous with the White working class. Kelley dispels this mythology – for more than 300 years there has been a Black working class though it has often gone unnoticed and underappreciated. With “Black Folk: The Roots of the Black Working Class” this hopefully will change.

“Black Folk” is extraordinary. The reader will come to understand that the Black working class has been central to the Black Experience in America. Black workers today are often are regarded as leaders within their communities and beyond. They were and continue to be trailblazers, helping to lead a new multiracial and multicultural working class generation.

The stories of Kelley’s family and others, through whose eyes much of the history of Black Folk is told, continue to be relevant today. As the author eloquently concludes,

“While race has been used by generation after generation of politicians [and is still being used] to divide and distract American workers from challenging the structural barriers that make it hard for the working class to get ahead, history and the present day are rich with promise. Indeed, if we better understand all the paths Black workers have taken, we can see what might be possible.”

Black Books, Black Minds” is a key foundation of my Great Books, Great Minds” passion project. For me, it’s a labor of love fueled by the endless hours of work I put into researching and writing these feature articles. My aim is to ignite a new world of community, connection, and belonging through the rich trove of Black History books, thought leaders, and authors we unearth.

So if you are enjoying this digital newsletter, find it valuable, and savor world-class book experience featuring non-fiction authors and book evangelists on Black History themes, then please consider becoming a paid member supporter at $6.00/month or $60.00/year.

I've made the purchase