In Chapter 8 of Rock My Soul: Black People and Self-Esteem,” renowned author, feminist, and social activist bell hooks (1952-2021) offers a thought-provoking look at the intersection between spirituality, music, and the Black American experience. Reading this book, I was reminded of the profound significance of these factors in shaping the cultural identity, resilience, and hopeful outlook of the Black community.

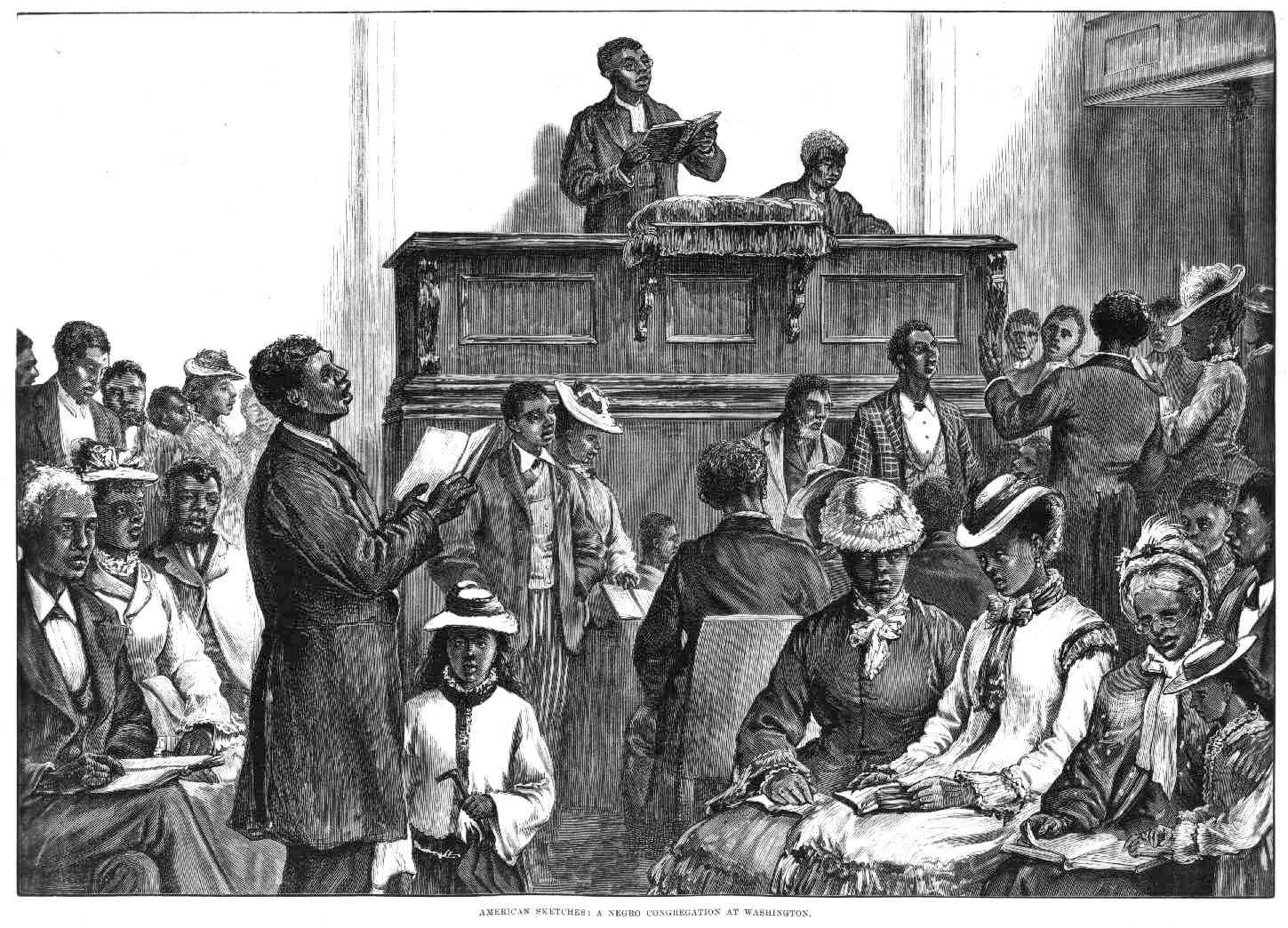

Growing up as a kid in Columbus, Ohio, attending Shiloh Baptist Church with my parents was my first exposure to the religious ways of us Black folks. It was the church that my grandparents, who were part of the Great Migration from the South, found their spiritual roots as newly minted Northerners.

In particular, I have fond memories of my grandmother whose faith was expressed with unconscionable depth. Hearing her sing Negro spirituals around the house, you knew that she felt it in the deep recesses of her being. She was also known for her legendary meal prayers that were at times so drawn out that the food she had prepared would be cold when she finished.

While in my thirties, I was a congregant for a number of years at Cathedral of Grace St John African Methodist Episcopal (AME) church in Aurora, Illinois. For me, it offered an eye-opening experience into the deeper history of Black History given AME’s distinction as the first independent Protestant denomination founded by Black people.

Drawing on historical and cultural contexts, Hook's in Rock My Soul examines the transformative power of music as a source of strength, healing, and resistance throughout African American history. She reflects on the ways in which gospel music, rooted in the African diaspora, has provided solace, inspiration, and a sense of unity in the face of adversity and oppression.

Through a blend of personal anecdotes, critical analysis, and cultural insights, hooks discusses how music transcends boundaries, fostering a sense of belonging among Black Americans. She underscores the importance of understanding the spiritual dimensions of Black music and its ability to uplift and empower individuals and communities.

In an excerpt from Chapter 8 of her book, she adds:

“Using the Bible as a source for self-esteem, black folks were able to counter the white supremacist insistence that they were less than human. The recognition of their essential humanity enabled displaced Africans to recover the will that enslavement had endeavored to break. From the testimony of slave narratives it is evident that enslaved black folk often experienced intense despair engendered by overwhelming feelings of powerlessness. Since the intent of colonization and slavery was to strip the slave of all agency, religious experience that enabled black people to identify with enduring the suffering of bondage while maintaining one’s hope was life sustaining.”

To this she adds that for Black folks, reading the Bible was a way for us to find peace in the belief that “obedience to the will of God was the only necessary requirement to be lifted out of slavery into freedom.”

As a practicing Buddhist, hooks' views on Black religious traditions were nuanced and respectful. She expressed both appreciation and a thoughtful critique of Black religious traditions, particularly Christianity.

Her approach is rooted in a commitment to social justice, intersectionality, and the exploration of spirituality that aligns with her Buddhist beliefs while respecting the diverse experiences and beliefs within the Black community.

bell hooks

In her work, she acknowledged the profound significance of Black churches in providing spaces for community, empowerment, and resistance against oppression. At the same time, she highlighted the ways in which certain aspects of traditional Christianity can reinforce patriarchy, sexism, and homophobia within the Black community.

Hooks encouraged critical examination and transformation within religious practices. She advocated for a deeper understanding of spirituality that transcends rigid dogma and encourages personal growth, liberation, and social justice. While she may critique certain aspects of Black religious traditions, hooks also recognizes the value of spiritual resilience and communal support that these traditions can offer.

Her approach is rooted in a commitment to social justice, intersectionality, and the exploration of spirituality that aligned with her Buddhist beliefs while respecting the diverse experiences and beliefs within the Black community.

As she notes in Chapter 8 in her book:

“Religion has played a crucial role in the historical development of self-esteem among African Americans. It served as a vital source of empowerment for both the small number of free Africans who came to these shores as immigrants or explorers and the large body of enslaved Africans. Fusing Christian traditions with the diverse spiritual traditions from Africa, black folks created ways to worship that were celebrating and life-sustaining.”

In a concluding thought from this chapter, she adds:

“Through their religious and spiritual experience enslaved Africans not only kept hope alive, they developed a liberation theology, designed to serve as a constant reminder of their right to freedom, to citizenship, to divine love.”

Black Books, Black Minds” is a key foundation of my Great Books, Great Minds” passion project. For me, it’s a labor of love fueled by the endless hours of work I put into researching and writing these feature articles. My aim is to ignite a new world of community, connection, and belonging through the rich trove of Black History books, thought leaders, and authors we unearth.

So if you are enjoying this digital newsletter, find it valuable, and savor world-class book experience featuring non-fiction authors and book evangelists on Black History themes, then please consider becoming a paid member supporter at $6.00/month or $60.00/year.

I learn the most from people’s personal stories. Thank you!

Very thoughtful analysis. Thank you.