In the soul of Eatonville, Florida, a town rooted in Black self-governance and literary history, rests the legacy of the Hungerford School, a once-thriving Black educational institution whose story deserves to be more than a footnote.

It is not just the tale of a school. It is the tale of Black America’s fight to build, to educate, to endure and to resist erasure.

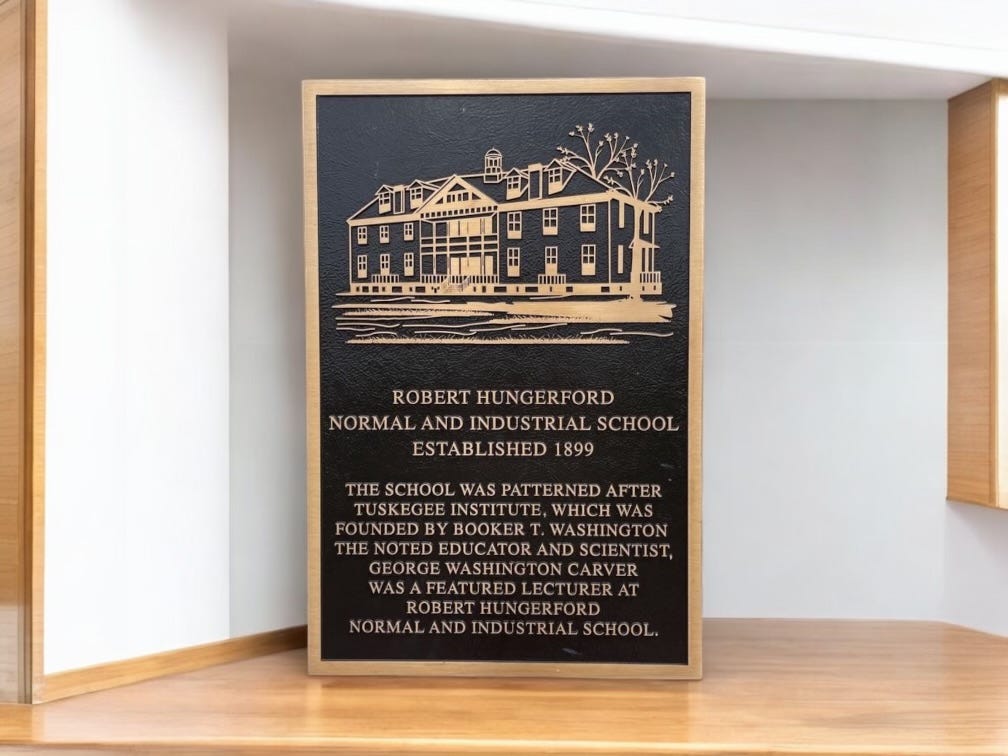

Founded in 1897 (some sources cite 1899) by Russell and Mary Calhoun, two Tuskegee-trained educators, the Hungerford School embodied the Booker T. Washington model of self-reliance, practical education, and community uplift.

Backed by the generosity of Connecticut philanthropist E.C. Hungerford who donated 160 acres in memory of his late son, the school grew into a 300-acre beacon for Black students during the harshest decades of Jim Crow segregation.

What strikes me most, as someone who walks the path of nomadic wisdom and deep cultural reflection, is that Hungerford was never just a school. It was an intentional act of defiance—a radical assertion that Black lives not only mattered, but could thrive through knowledge, discipline, and collective work.

In an era when laws, customs, and systems conspired to keep Black minds stunted, Hungerford cultivated them through gardens, radio technology, Latin, poultry farming, and Shakespeare.

A Model of Self-Determined Education

What was revolutionary about Hungerford was that its students didn’t just learn, they labored, contributed, and sustained their education through farming and maintenance work.

That’s not exploitation; that’s empowerment. This was a form of soul-rooted education that nourished dignity along with literacy. Hungerford taught its students that survival and excellence were not opposites, but intertwined paths. It mirrors the broader idea of finding harmony through natural rhythms—of learning by doing, by contributing, by becoming a part of something larger than the self.

As a passionate observer of natural systems and cycles, I see Hungerford’s story as part of a repeating pattern in Black history: we create, they absorb; we plant, they pave over.

The school’s transition to public control in the 1950s marked a shift from Black-led vision to state management. The land which was given explicitly to educate Black children slowly began to disappear, sold off parcel by parcel by Orange County Public Schools.

And here’s the gut punch: by the 2020s, what was once 300 acres had been reduced to 100, and now OCPS offers a symbolic 10 acres for a museum. Ten acres of a dream.

Land Theft Disguised as Progress

The story of Hungerford is not just about education. It is about land, the most fundamental currency of power and permanence in America. Hungerford’s story reminds us that when Black institutions are no longer convenient for those in power, their lands are “redeveloped,” their histories rebranded, and their legacies erased. The land theft is a modern continuation of an old American tradition: dispossession under the guise of bureaucratic progress.

And yet, the resistance is growing. Eatonville’s residents, alongside advocates like the Association to Preserve the Eatonville Community and the Southern Poverty Law Center, are demanding not just a museum, but reclamation of land, memory, and agency. That resistance is a spiritual act, an act of memory, a defiant flow returning back to origin.

A Sacred Call to Remember

The Hungerford School may be closed, but it is far from forgotten. Its spirit lives on in every child who dreams bigger because someone before them tilled the soil.

It lives on in the annual ZORA! Festival, in the dreams of a future Black history museum, and in the ongoing struggle to keep Eatonville’s story alive.

What’s needed now is not nostalgia but activation. Black historical education is not a luxury but an armor. In an age of book bans and whitewashed curricula, the Hungerford legacy offers a powerful model for educational sovereignty. It reminds us that land is sacred, that memory is resistance, and that schools are temples of the possible.

In a time of cultural amnesia, Hungerford is a lighthouse. Will we answer its call?

If you are finding “Black Black, Black Minds” to be a valuable resource in learning about Black History , then please consider supporting my work by subscribing as a paid member or tipping some dirty chai latte love.

No paywalls—just raw, well-researched feature articles delivered straight to your inbox. Every contribution helps keep this journey alive. you contributions will be greatly appreciated.

Diamond Michael Scott, Global Book Ambassador, The Great Books, Great Minds Family of Books

This piece is resonant. I’m in the middle of writing a book proposal and have a chapter dedicated to schools that didn’t survive post segregation. I’m focusing on Charlotte Hawkins Brown’s Palmer Institute. I absolutely love the way you articulated the importance of these spaces.

Thanks for this quick, important information. I had never heard of the school or the story!

Stay cool 😎 metaphorically & literally.