The Pullman Porter Legacy

Masters of Their Own Fate and Architects of the Black Middle Class

Would you be kind enough to consider becoming a “Black Books, Black Minds” member supporter?

At $6.00/month or $60.00 year, your funds will help me continue to build this labor of love and deliver great Black History content to you.

Click below to update. Every little bit counts

Thank you!

Diamond-Michael Scott

The Pullman National Monument and Historic Park is a historic district located in Chicago, Illinois, which is the 19th century was the first model, planned community in the United States

In the dawn of America’s industrial age, one visionary redefined luxury travel—George Pullman, an ambitious industrialist who founded the Pullman Palace Car Company in 1867. Pullman wasn’t just selling a ticket; he was selling an experience of grandeur on rails.

His train cars, deemed “Palace Cars,” became icons of status, elegance, and refinement. But behind the polished mahogany panels and plush velvet seats lay a radical social experiment that would ignite a quiet revolution and birth a powerful legacy.

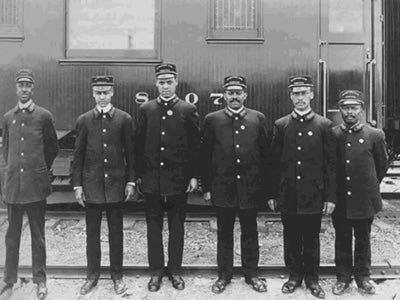

The true heartbeat of the Pullman empire was not its opulent cars, but the Black men who served within them—the Pullman porters. These men, once enslaved or children of the formerly enslaved, were recruited to work relentless shifts, often up to four hundred hours a month.

Their duties were many: hauling heavy luggage, shining shoes, serving meals, and maintaining the luxury of the railcars, performing with the dignity and poise of a modern day flight attendant.

Yet, unlike their passengers, all the porters were Black—a deliberate choice by George Pullman, who believed these men would work tirelessly for modest wages while seamlessly blending into the background of white affluence.

However, the story of the Pullman porters is not merely one of subservience; it is one of profound paradoxes and power. In their subservient roles, they found subversive opportunities—grasping control of their destinies, leveraging the system to elevate themselves, their families, and ultimately, an entire race.

The Invisible Influencers of Black America

Who was the most influential Black man in America post-Civil War? According to Larry Tye, author of “Rising From The Rails: Pullman Porters and the Making of the Black Middle Class”:

“THE MOST INFLUENTIAL black man in America for the hundred years following the Civil War was a figure no one knew. He was not the educator Booker T. Washington or the sociologist W. E. B. DuBois, although both were inspired by him. He was the one black man to appear in more movies than Harry Belafonte or Sidney Poitier. He discovered the North Pole alongside Admiral Peary and helped give birth to the blues. He launched the Montgomery bus boycott that sparked the civil rights movement—and tapped Martin Luther King Jr. to lead both. The most influential black man in America was the Pullman porter.”

Indeed, these unassuming men were more than mere attendants; they were cultural conduits, quietly reshaping American society. They helped spread “The Chicago Defender,” a progressive Black newspaper banned in the South, by tossing bundles of papers from train windows to awaiting hands. They connected Black communities, disseminating ideas that ignited the Great Migration and fueled the civil rights movement.

Economic Ascent and Cultural Resilience

To many in the Black community, becoming a Pullman porter was an esteemed path—a ticket to economic advancement without the backbreaking degradation of sharecropping or domestic servitude.

In 1926, Pullman porters earned about $180 a year (roughly $7,500 in today's dollars), significantly more than most Black Americans could make at the time.

The work afforded them a glimpse of the broader world, laying a foundation for future generations to break through the color line and enter mainstream professional realms—some even working their way into the White House, like porter J.W. Mays, who served for nine U.S. presidents.

Yet, this upward mobility was no easy feat. Pullman porters faced degrading conditions and endured systemic racism. They were often called “boy” or “George,” a lingering vestige of slave names linked to their former owners. Still, many porters wore their uniforms with pride and served with a fierce sense of purpose.

The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters: Defiance and Liberation

When the exploitation became too much to bear, the porters organized. In 1925, labor leader and civil rights icon A. Philip Randolph founded the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP), the first Black labor union in America.

Randolph’s movement, born out of the struggles of the Pullman porters, eventually forced the company into a landmark agreement in 1937—the first collective bargaining agreement between Black workers and a major American corporation.

This victory set the stage for broader civil rights achievements, like President Franklin Roosevelt’s Executive Order 8802 in 1941, which outlawed discriminatory hiring in the defense industry.

Randolph’s leadership, grounded in self-reliance and community, echoes the tenets of libertarianism, even though he was a socialist. His philosophy underscores a universal truth: that freedom and equality are not granted—they are won through relentless effort and collective power.

A Legacy of Freedom and Defiance

The legacy of the Pullman porters is a tale of transformation—an audacious ascent from servitude to citizenship, from invisibility to influence.

Their quiet defiance against a backdrop of racial subjugation is rarely highlighted, yet it laid the groundwork for Black middle-class stability and independence. Generations later, the children and grandchildren of porters, from Justice Thurgood Marshall to jazz icon Oscar Peterson, carried forward this torch of defiance and aspiration.

The Pullman porter’s story is not just Black history; it’s American history—a testament to the enduring power of dignity, resilience, and the relentless pursuit of self-determination.

And perhaps the greatest lesson of the Pullman porters is this: that within the constraints of a deeply intolerant society, they became masters of their own fate, laying the stepping stones for the generations to follow.

Excellent article. Thank you for sharing the foundational legacy of Black people. I knew a little about the Pullman Porters but not to this detail. I wonder if you could share about the Yale Black Chef’s Club. That’s what I have heard it referred as. An all black male chef’s club considered to be prestigious at Yale University.

Bought the book. Needs lots of inspiration these days. Thank you!